February 23, 2017

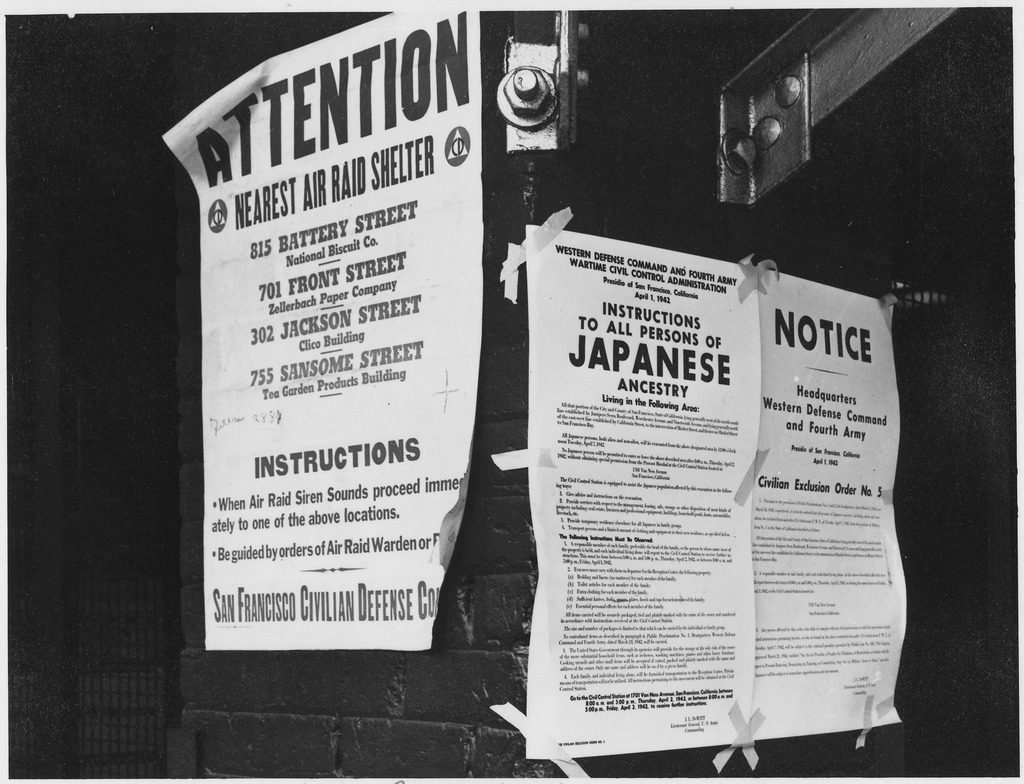

Stories of resistance to World War II incarceration often include Gordon Hirabayashi, Minoru Yasui, Fred Korematsu, and Mitsuye Endo. These are the most famous Japanese Americans who resisted the racially based curfew and exclusion, and later the mass incarceration. Their resistance led to the U.S. Supreme Court, and they are all deserving of the recognition they’ve received. But did you know that beyond this group, there were a good number of others who willfully disobeyed the exclusion orders authored by EO9066?

Here, in brief, are a few of their stories.

Beyond the big four “Japanese American cases,” there were several others who challenged aspects of the exclusion in the courts. Among the first was a habeas corpus petition filed in Seattle on April 13, 1942 on behalf of Mary Asaba Ventura, a Nisei, that challenged the legality of the curfew order. In denying the petition two days later Judge Lloyd L. Black—who would also preside over the Hirabayashi case six months later—denied her petition, vehemently questioning the loyalties of Japanese Americans along the way.

At about the same time in Los Angeles, Ernest and Toki Wakayama, a Nisei couple, asked ACLU lawyer A.L. Wirin about possibly challenging the forced removal. As a married couple with children, they decided to comply with the “evacuation orders” and report to the Santa Anita Assembly Center, with the intent of challenging the orders once there. In August 1942, Wirin filed habeas corpus petitions on their behalf. As a Hawaii-born Nisei World War I veteran and American Legion officer, Wakayama seemed like an ideal test case. But when the Wakayamas later decided to repatriate to Japan, they dropped the petitions. Their subsequent wartime and postwar odyssey deserves its own book someday.

Lincoln Kanai, another Hawaii Nisei, was the executive secretary of the Buchanan Street YMCA in San Francisco before the war. Seeing the wrongness of the exclusion policy, he tried to get authorities to change it through official channels. But when that failed, he simply refused to report for removal on May 20 and left the city on June 1. He spoke to students groups and others about the removal in areas outside the restricted area until he was arrested by the FBI on July 11. After filing a habeas corpus petition that was denied, he was tried in San Francisco under Public Law 503 and found guilty. On August 27, he was sentenced to six months in prison. Unlike the others, he decided not to appeal and was “released” to Heart Mountain in February 1943.

[As an aside: did you ever notice that a seemingly disproportionate share of camp-era dissidents were from Hawaii? In addition to Wakayama and Kanai, there is also “Manzanar Martyr” Harry Ueno, Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee (FPC) founder Kiyoshi Okamoto and FPC treasurer Tsutomu Ben Wakaye, and of course the notorious Joe Kurihara. Though not exactly a dissident, wartime JACL president Saburo Kibo was also from the islands. I’ll save my thought on why this might be for a later post.]

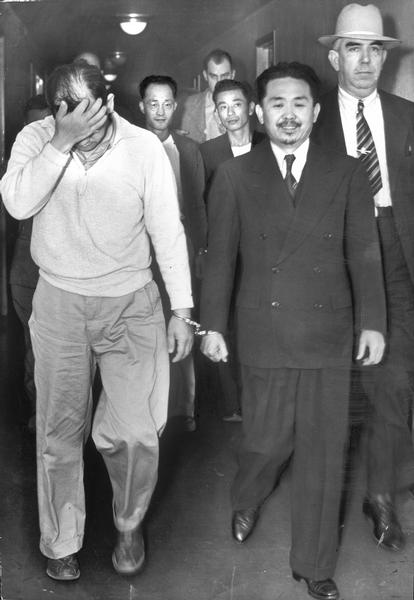

Beyond those that sought redress through the courts, there were a good number of others that just refused to report when they were supposed to. Newspapers in the weeks after exclusion mention a bunch of such cases. Perhaps the best known is that of Koji Kurokawa, a handyman in San Francisco who hid out in his employer’s basement for twenty-three days before finally being found. He pled guilty and was sentenced to six months in the county jail.

In June, authorities arrested Taneji Tsumura in LA, Katsumi Chikasue in Sacramento, John Ura in the San Francisco area, and Liwa Yakai Chew in San Francisco. In July, there was John Takeo Ui of Sacramento, Mr. and Mrs. Harno Iwataki in Sonora, and S. Torosu. In the case of the latter, the 69 year old Issei laborer as found living along the San Joaquin River where he had been hiding for month, living on fish he had caught and stolen vegetables. In August, there was Midori Murokita, found hiding on a ranch in Milpitas. In September, Pat Brennan Kawasaki, a mixed race young man who had been posing as Mexican, was arrested in San Jose. In October, Morris Eugene Suyetomi, another mixed race man, surrendered. Sent to Topaz, Suyetomi left camp in 1943 for a job in Salt Lake City. He was arrested again when he went back to San Francisco to work in a steel plant, passing as Chinese. In October, Emil Tore was found in the back of truck after a collision, while Kumahichi Yoshida was arrested in San Francisco, where he had been posing as a Korean. The list goes on.

There are at least a couple of cases of Japanese Americans who may have successfully evaded removal and incarceration. In a 1974 article, Ruth Yamazaki writes about her brother and sister-in-law who avoided removal by passing as Koreans named “Lee” while working as domestics in Los Angeles. She writes that they were able to keep up the ruse for a year, then rejoined the rest of the family who had resettled in Michigan from Poston.

The second case is described by historian Allison Varzally. Mrs. Tien Gee, a Japanese American married to a Chinese American, passed as Chinese, with the couple continuing to run their barbershop in Los Angeles Chinatown. When an FBI agent came looking for her, locals denied knowing of her, even as she was right there cutting hair.

(There is a whole other story to tell about mixed-race individuals or families that is hinted at in some of these cases. I’ll get to that in a future post as well.)

No one has looked at these types of cases in any systematic way, so there is much research that can be done if anyone is so inclined. The point here, though, is that contrary to popular belief, there were a good number of Japanese Americans beyond the Big Four who resisted calls for curfew and/or incarceration, and there may even have been some who managed to elude capture.

Have you heard of other such stories?

—

By Brian Niiya, Content Director and editor of the Densho Encyclopedia

To learn more about Kanai and his case, see the Densho Encyclopedia article by Kyna Herzinger.

[Header photo: Japanese Americans were given little time to take care of their personal and business affairs once the exclusion orders were posted. Many businesses were either permanently closed or boarded-up for the duration of World War II. Shown here is 602 to 612 Jackson Street in Seattle’s Nihonmachi, or Japantown, 1942. Courtesy of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Museum of History & Industry.]