September 26, 2025

The imagery of barbed wire fences, guard towers, and armed sentries is nearly ubiquitous in popular retellings of the story of Japanese American WWII incarceration. But did you know that many of the camps didn’t have a complete fence when Japanese American incarcerees began to arrive in 1942? In this latest edition of our recurring Ask a Historian series, Densho Content Director Brian Niiya delves into the complicated history “behind the barbed wire,” responding to a question from a survivor of Gila River’s Canal Camp:

“I don’t recall a barbed wire fence at Canal Camp and have not seen a security guard tower in any photographs. Did Gila River have these things?”

From time to time, we have gotten questions about the infamous barbed wire fences that ringed the War Relocation Authority (WRA) concentration camps. Did all of the camps have them? Did the fence situation change over time? Did they actually keep people in or out? As with most things involving the WRA, the answers are complicated.

Unfinished Camps with Unfinished Fences

When incarcerees first began to arrive at the ten WRA camps, they were unfinished to varying degrees. Construction on what would become Manzanar started just days before the first “volunteers” arrived on March 21, 1942, and those early “volunteers” subsequently played a large role in building the camp. While Manzanar was extreme in the degree that the camp was unfinished as incarcerees arrived, this general pattern took place at all of the other WRA camps.

Among the elements that were often unfinished were the fences. In fact, at most of the camps, the fences were either not yet built or were in the process of being built as incarcerees first arrived. Though there is sometimes conflicting information, I believe that the status of the fences upon arrival was as follows:

We should note that at least one of the camps that didn’t have a fence at opening—Heart Mountain—did have guard towers as the incarcerees arrived.

There’s an obvious pattern here, with the camps that opened earlier not having fences initially and the ones opening later having them. This makes sense intuitively, since the later-opening camps would presumably have been in a more finished state than the earlier ones.

Tule Lake is the outlier here. The camp newspaper, The Tulean Dispatch, mentions the fence in articles in July, while the ever observant James Sakoda—a fieldworker for the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study—notes the fence and a guard tower shortly after his arrival in mid-June. So it seems the fence there was already in place upon opening.1

Over the course of the fall (or earlier with Manzanar), fences went up in the various camps that didn’t have them, at the behest of Western Defense Command. Recall that while the War Relocation Authority controlled things inside the camp, the army—generally manifested by a military police company stationed just outside the camp—was in charge of the camp’s perimeter, including entry and exits into and out of the camp. The WRA and army often clashed over the level of enforcement of camp boundaries and the necessity of guards, guard towers, and fences.

Resistance to the Fences at Some Camps

As you might imagine, the seemingly sudden need to build fences did not go over well with incarceree populations that had gotten along fine for weeks or months without them. While there was assorted grumbling about the fences at all of the camps where this took place, there were more major disturbances and protests about the fences at two of the camps.

When incarcerees began arriving at Heart Mountain in August 1942, there were eight guard towers along the perimeter of the camp, but no fences. In October, construction on the barbed wire fences began, immediately capturing the attention of the incarceree population. Incarceree workers hired by the contractor to build the fence walked off the job, and some Nisei members of a commission formed to draft a charter for the camp walked out of a meeting when it became clear they could do nothing about the fence. Project Attorney Jerry Housel wrote that since the fence was built, it came up “with a rather bitter tone” at “practically every meeting or discussion group.” Even the largely pro-administration Heart Mountain Sentinel ran an editorial noting that the fence “created a wave of consternation among the evacuees…. creating definite ill-feelings.” Discontent peaked with a November petition to WRA Director Dillon Myer that was signed by 3,000 incarcerees, calling the fence and guard towers “ridiculous in every respect, an insult to any free human being” and “devoid of all humanitarian principles, understanding, and principles of democracy.”2

Meanwhile, at Minidoka, the administration briefly electrified the fence in response to protest by incarcerees. After some three months without one, construction on a fence suddenly began on November 6, outraging incarcerees. Beyond symbolism, the fence created inconvenience and even danger, since it cut off access to farming areas, a dump area, and the canal, and divided a pond that incarcerees used for ice skating. Over the next few days, incarcerees began to cut wires and uproot posts in protest. The fence contractor reacted by electrifying the fence on November 12, though the administration made them turn it off after a few hours upon learning of it.

In January, Reports Officer John Bigelow wrote that “reaction to the barbed wire fence… isn’t abating.” (Though Bigelow was seemingly sympathetic to the incarcerees on the fence issue, he also asked the camp newspaper not to print any editorials or letters to the editor that criticized the fence, in contrast to his Heart Mountain counterpart.) Community Analyst John de Young wrote that the “residents are unanimous in possessing deep and bitter resentment against the fence.” After some ice skaters cut themselves on the fence in January, incarcerees cut back part of the fence; though MPs noticed, they did not stop it, and the fence was not fixed. Much of the fence was removed in April to allow greater access to farming areas and was never replaced. Incarcerees salvaged the posts and barbed wire to make fences and clotheslines for their blocks.3

After the fence building rush in the fall of 1942, most of the WRA camps were surrounded by barbed wire fences and some number of guard towers, with the MP compounds outside the fence. This is where things stood at the various WRA camps at “peak fence” in late 1942/early 1943:

- Manzanar: five-strand barbed wire fence and eight guard towers4

- Tule Lake: four-foot-high barbed wire fence with guard towers at the four corners5

- Poston: fences around each of the three sub-camps, but no guard towers6

- Gila River: fences around each of the two sub-camps; one guard tower7

- Minidoka: four-strand, five-foot-high barbed wire fence with eight guard towers8

- Heart Mountain: barbed wire fence with nine guard towers (the ninth guard tower was added in December)9

- Amache: four-strand barbed wire fence with eight guard towers; fence between inmate and administration areas erected in December 1942, but quickly taken down10

- Topaz: barbed-wire fence with six guard towers11

- Rohwer: barbed-wire fence with eight guard towers12

- Jerome: four-strand barbed-wire fence with seven guard towers13

The Fence Frenzy Wanes Over Time—But Not for Camps Inside the “Exclusion Zone”

In most cases, strong incarceree objections to the fences did not lead to their coming down. But for a variety of reasons—mostly a recognition by the army, WRA, and local communities that the incarcerees presented no threat and that it was a waste of time and resources to continue to enforce camp boundaries—the general level of concern about the fences began to wane over time, at least at the camps outside the restricted area. The fences did come down at a couple of the camps: Minidoka, as noted above, and Gila River, in the spring of 1943. But this trend was gradual and certainly not universal, as evidenced by the infamous shooting of Topaz inmate James Hatsuaki Wakasa by a guard atop a guard tower in April 1943.14

More typical was the situation at Heart Mountain, where the fences remained up, but the ranks of the MPs were halved in early 1944, and MPs were removed entirely in August 1944. Guard towers stopped being manned sometime in 1943. Incarcerees were subsequently tacitly allowed to hike and picnic outside the fence, as well as to gather raw materials for gardens and craft projects. A similar easing of security took place at most other camps.

Things were a bit different at the camps within the restricted area, which included only the California camps, after the shifting of exclusion zone boundaries in March 1943 moved the Arizona camps into the “free” area. Most of you reading this will know that in the fall of 1943, Tule Lake morphed into the “segregation center” for those deemed “disloyal.” In addition to seeing its inmate population increase dramatically, the new Tule Lake was heavily fortified, with a heavier barbed wire fence added, along with a new gate and a dramatic increase in the number of guard towers. Adding to the prison-like atmosphere was the arrival of a battalion of some 1,000 MPs and tanks parked in front of the administration area.

Given its location at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains and the relatively mild climate—along with the discovery of some popular fishing spots—incarcerees at Manzanar frequently left the camp to pursue various kinds of outdoor recreational activities. But given that it was within the exclusion area, Manzanar’s MPs and administration were more vigilant in trying to enforce the boundaries. When a new MP company was assigned to Manzanar in June 1943, its commander, Captain Donald R. Nail, reiterated that incarcerees were “not to go under the fence to go after baseballs, golf balls, or for any other purpose,” and if they needed to go out, they “must use the gates and secure permission from the M.P. on duty.” When a reduction of the MPs in 1944 led to more incarcerees going outside the fence, Manzanar Director Ralph Merritt threatened violators with “30 days at the county jail in Bishop.” Incarcerees nonetheless continued to go out to hike, picnic, and fish. There is even a feature length documentary on this topic.

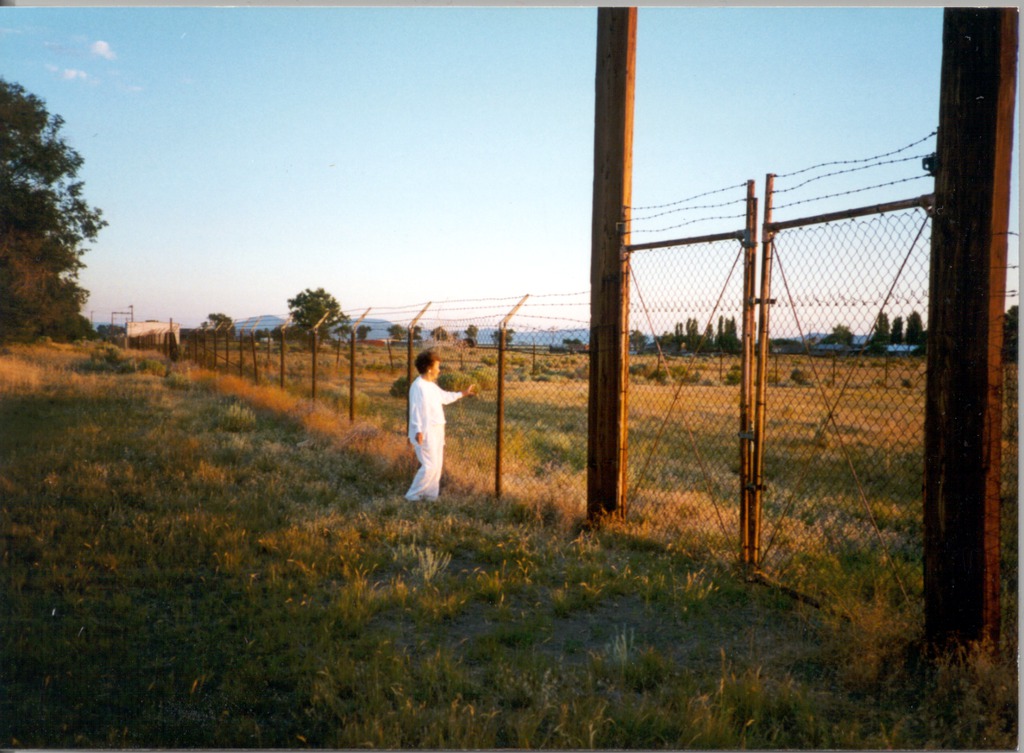

The Fence as an Enduring Symbol of WWII Incarceration

I should note that there are many retrospective accounts in oral histories or memoirs—including many in Densho’s collection—where former incarcerees recall the shock of seeing the fences and guard towers as they first arrived at a WRA concentration camp that we know didn’t have one or both at that time. Given that all of the camps did eventually have fences and/or guard towers later—and that these events took place over eighty years ago—it is easy to understand how memories like this can be a bit unreliable.

Despite the ebb and flow of fence policy over time, the fences and guard towers became a potent symbol of incarceration for many Japanese Americans, perhaps summed up best by the viral circulation from camp to camp of “That Damned Fence,” a poem of uncertain authorship, starting in the fall/winter of 1942—the general period of peak fence. In the years since, innumerable accounts in oral histories and memoirs by former incarcerees highlight the impact of the barbed wire fence, the guard towers, the guns “pointing in and not out.” There are books and films titled “Birthright of Barbed Wire,” “Behind Barbed Wire,” “Poets Behind Barbed Wire,” “Beyond Barbed Wire, “Life Behind Barbed Wire,” Barbed Wire Baseball,” and that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

So to get back to the original question, yes, there were fences for at least part of the time at all of the WRA camps, including Gila River, if only briefly. But given the slightly muddled yet revealing accounts of incarcerees remembering fences that weren’t there yet as they arrived at their WRA concentration camps, we need to be careful in recounting this history in all of its complexity. As with many complex stories, what actually happened can be even more interesting than the simpler and often repeated versions.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

Footnotes

- James Sakoda Journal, June 15 and 17, 1942, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records (JAERR), Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder R 20.81:02**; “History Has Rhythm,” Tulean Dispatch, July 11, 1942, p. 2 and “Hi, Neighbors!,” Tulean Dispatch, July 23, 1942, 2. ↩︎

- Douglas W. Nelson, Heart Mountain: The History of an American Concentration Camp (Madison: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin for The Department of History, University of Wisconsin, 1976), 19, 83–85; Jerry W. Housel, Project attorney report, Nov. 17, 1943, p. 5, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records (JAERR), Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder M1.35:1; Heart Mountain Sentinel, Nov. 21, 1942, 4, 6. ↩︎

- John de Young, Community Analysis Section, “Notes on the Fence, Watchtowers and M.P.’s,” April 27, 1943, Community Analysis Reports and Community Analysis Trend Reports of the War Relocation Authority, 1942-1946, Microfilm Reel 22 (Washington, [D.C.]: National Archives, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 1984); John Bigelow, Minidoka Reports No. 30, Jan. 14, 1943 and No. 45, Feb. 20, 1943, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder P3.95:1; Barbara Johns, Signs of Home: The Paintings and Wartime Diary of Kamekichi Tokita (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011), 228n80. Note that Minidoka’s unique shape—it meandered along an irrigation canal for nearly three miles and was thus not a square or rectangle like all of the other camps—meant that there was more fencing and that this fencing was likely more difficult to police. ↩︎

- Harlan D. Unrau, “Chapter Eight: Construction and Development of the Manzanar War Relocation Center—1942–1945,” The Evacuation and Relocation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry During World War II: A Historical Study of the Manzanar War Relocation Center, Historic Resource Study/Special History Study, 2 Volumes ([Washington, DC]: United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1996). ↩︎

- Shotaro Frank Miyamoto, “Chapter I: Introduction,” The Tule Lake Report, Nov. 30, 1944, p. 18, JAERR, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder R 20.65:1; James Sakoda, “Description of Tule Lake Japanese Colony,” June 22, 1942, p. 3, JAERR, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder R 20.80. ↩︎

- Karl Lillquist, “Imprisoned in the Desert: The Geography of World War II-Era, Japanese American Relocation Centers in the Western United States” (Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, September 2007), 415. ↩︎

- Charles Kikuchi and Robert Spencer, “Evacuee and Administrative Interrelationships in the Gila Relocation Center,” March-April, 1943, Physical Description 3, JAERR, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder K8.31. ↩︎

- Monroe E. Snyder and Arthur E. Ficke, “Report of the Engineering Section, Minidoka,” p. 7, JAERR, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder P6.00:13; de Young, “Notes on the Fence,” 2. ↩︎

- [Heart Mountain] “Engineering Section Final Report,” pp. 14–15, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder M1.05:4; Nelson, Heart Mountain, 19, 83. ↩︎

- Lillquist, “Imprisoned in the Desert,” 42; Dismantling Amache: Building Stock Research and Inventory Related to the Granada Relocation Center (Denver, Colo.: Friends of Amache and Colorado Preservation, Inc., August 2011), 21; Donald T. Horn, Project Attorney Weekly Reports, Dec. 5 and Dec. 15, 1942, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder L1.61:1. ↩︎

- [Topaz] “Report of the Engineering Section, Beginning of Center, September 1942 to Closing of Center, January 1946,” pp. 15–16, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder H12.00:10; “Guidebook of the Center,” Project Reports Division Historical Section, Sept. 1943, Illustrated by Yuri Sugihara, p. 2, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder H12.00:2. ↩︎

- Kango Kunitsugu, ed., Rohwer Reunion Booklet (Gardena, Calif.: First Rohwer Reunion Committee, 1990), p. 17, California State University, Dominguez Hills, Archives and Special Collections, CSU Japanese American Digitization Project. ↩︎

- Maury A. Church, Final Report: Operation Division/Engineering Section, pp. 14, 17, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder N5.00:12. ↩︎

- Lillquist, “Imprisoned in the Desert,” 483–84; L H. Bennett, [Gila River] Closing Report, July 23, 1945, p. 13, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder K7.50:3. ↩︎

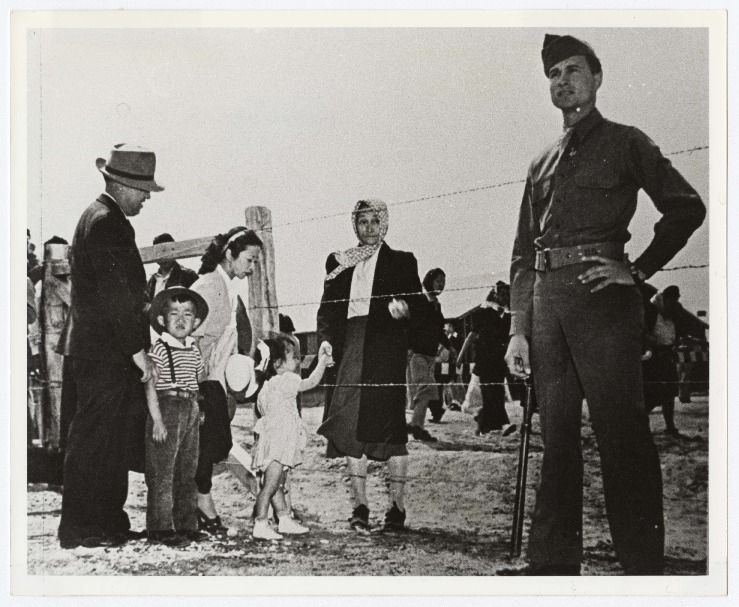

[Header: Military policeman patrolling camp fence at Santa Anita Assembly Center. April 6, 1942. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]