July 12, 2021

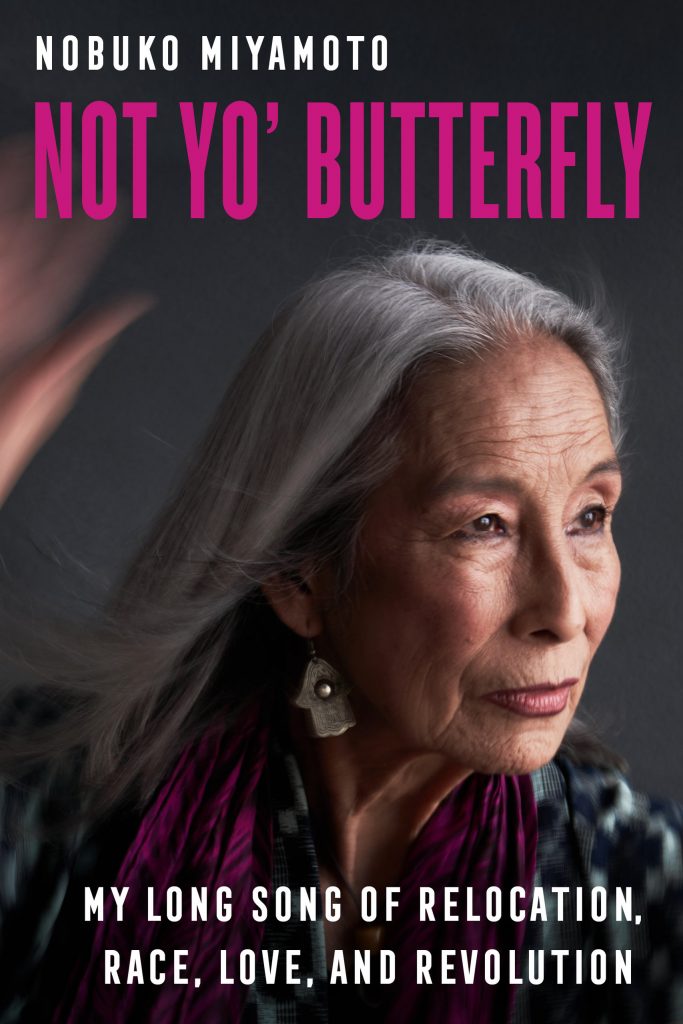

As a musician, artist, and activist, Nobuko Miyamoto has long used art to create social change and solidarity across cultural borders. Her new memoir, Not Yo’ Butterfly: My Long Song of Relocation, Race, Love and Revolution, retraces that journey, from her early years in a WWII incarceration camp to her involvement in the Asian American and Black Liberation movements. In this excerpt from Not Yo’ Butterfly, Miyamoto describes joining a group of young Asian American activists on a revelatory trip to the Black Panthers headquarters in Chicago in 1970.

See Miyamoto at a virtual book event presented by the Seattle Public Library, Seattle JACL, Densho and the Elliott Bay Book Company on Thursday, July 22. Learn more and reserve your free ticket here.

In 1968, Chicago grabbed the eyes of the world when fifteen thousand Vietnam anti-war protesters vowed to shut down the National Democratic Convention and iron-fisted Mayor Daley unleashed the largest, bloodiest police riot ever seen on television. In December 1969, Fred Hampton, leader of the Black Panthers, was assassinated by Chicago police. This was the Chicago our New York Asian American caravan rolled into that summer of 1970.

We’d come to push the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) to take a position against the Vietnam War, but Chicago delivered a series of unexpected revelations that began when we landed at the church where we were staying. Warren Furutani, Victor Shibata, and the West Coast contingent were there to greet us with open arms and more power handshakes. They came from all over California: Los Angeles, San Francisco, Sacramento, Stockton, San Jose, Fresno. It was the first meeting between Japanese American activists from East and West, but it felt more like a family reunion, only on steroids. In the social hall, conversations were buzzing over tables with a spread of Japanese picnic foods—onigiri made with loving hands, teriyaki chicken, and of course potato salad. That plus trading stories of the work we were doing created instant love. In fact, I’ve never felt that kind of love before. It was bigger than personal love. It was love of our people, love of who we were, love of who we were becoming.

Our experiences were as distinct as our geographic landscapes, yet from Sacramento to Manhattan, we were infected with the same set of beliefs. We were using our experiences and cultural roots to reach, to serve, to organize, to liberate ourselves and our communities, to be an integral part of the bigger struggle to make fundamental change in this country and the world. We called this change “revolution.” In Chicago, our big revelation was that we weren’t just a smattering of Asian groups on campuses and in communities trying to stop the war and serve our people. We were a movement—the Asian American Movement.

The next day our gathering spilled into the streets of Chicago. Chris Iijima and I went with a contingent to meet with the Panthers, the political epicenter of the Black community. We wanted to pay homage to their leader, Fred Hampton, and show our solidarity during this time of repression by the Chicago Police Department. The Panthers welcomed us like brothers and sisters, men clasping hands in the Black Power handshake, a physical expression of solidarity. We met in the same office the Panthers had defended from a police attack just months before. Several Panthers had been arrested, and two Party members as well as five officers were wounded. The police torched the room that stored “dangerous contraband”—boxes of cereal that they served in their breakfast for children program. The office was freshly painted and the bullet holes from the police attack had been covered with help from the community. And breakfast was still being served. These young men and women Panthers were beleaguered, but they were carrying on.

Their voices warmed when they talked about their brother Fred Hampton and his words, “the people’s beat.”

Hampton’s organizational skills, charisma, and integrity were making him a respected leader who was instilling a sense of pride, dignity, and self-determination in his people. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover feared him as the next possible Malcolm X. And so on December 4, 1969, police assaulted Hampton’s apartment on Monroe Street shortly before five in the morning. They seemed to know what Party members would be there, where their cache of guns was stored, and where Hampton slept. It was later revealed that Hampton had been drugged, and so was unable to awaken when they murdered him in his bed. Their automatic weapons dispensed nine hundred bullets, but the Panthers only returned one. At the age of twenty-one, Fred Hampton had become a sacrificial lamb for speaking out for his people.

The Panthers knew our story: they knew about camp and accepted us as part of the oppressed Third World People within the United States. But being herded to camp seemed to me a smaller injury compared to their struggle. We behaved, kept silent, and some nisei young men made the ultimate sacrifice to prove we were good Americans. In three or four years we were released to face the hardship of loss and rebuilding our lives. Japanese endured through gaman. But could we have endured and behaved through four hundred years of slavery, economic hardship, lack of educational opportunity, containment, and police repression that keeps Black people in their “camp” to this day?

Walking back to the church from the Panther headquarters, a strange vision stopped us in our tracks. A giant tepee stood at the entrance to Wrigley Field, leather skins wrapped around a triangle of poles piercing the sky. I’d never seen a real tepee—so simple, so beautiful. When we approached, we found out it was part of a Native American protest, a cry for decent housing for urban Indians. We must have looked like another tribe to them. They stopped leafleting and invited us to sit in their circle. Some of us sank cross-legged to the ground, while some sat on makeshift chairs.

A silence descended as an elder began to chant. A long pipe was lit and offered in six directions—east, west, north, south, above, below. The pipe was then passed around the circle. I never smoked but drew a breath of the sweet tobacco into my mouth. I looked at the faces in the circle, and Chicago and Wrigley Field disappeared. We were in another time and space. In the circle an elder shared a story. He told us there would be five thousand years of evil, followed by five thousand years of good, and that change would come to be when warriors of all colors of the rainbow came together. It was the prophecy of the Warriors of the Rainbow. We drew in the story like the smoke from the pipe and held it like a secret, deep inside. When it was time to leave, we thanked them and took the story with us as we walked back to the church. I couldn’t talk. I just walked, holding the story in me, my feet feeling the earth through the concrete.

We passed through a German neighborhood. A rowdy group of young men watched us from their porch. They threw beer and Coke cans at us as we passed, punctuated with “You dirty Japs! Chin Chin Chinaman!” They brought us back to the unreal world, to Chicago, but we kept our stride. The stones of their words rolled off us without a bruise. This time we had our armor; we knew our story.

—

This edited excerpt from Not Yo’ Butterfly: My Long Song of Relocation, Race, Love, and Revolution by Nobuko Miyamoto and edited by Deborah Wong (University of California Press, 2021) is reproduced with the permission of the author and publisher.

Nobuko Miyamoto is a third-generation Japanese American songwriter, dance and theater artist, and activist, and is the Artistic Director of Great Leap. Her work has explored ways to reclaim and decolonize our minds, bodies, histories, and communities, using the arts to create social change and solidarity across cultural borders. Two of Nobuko’s albums are part of the Smithsonian Folkways catalog: A Grain of Sand, with Chris Iijima and Charlie Chin, produced by Paredon Records in 1973, and 120,000 Stories, released by Smithsonian Folkways in 2021.

[Header photo: Attallah Ayubbi and Nobuko march in a Republic of New Africa demonstration at the United Nations, New York, ca. 1973. Author’s collection.]