April 3, 2023

In February of 1973, American Indian Movement activists began the occupation of Wounded Knee. Over the course of the 71-day occupation, Indigenous activists and allies – including a delegation of Asian Americans – traveled from across the country to join them in solidarity. As Nick Estes explains in his book, Our History is the Future, they were acting at the behest of Oglala elders and protesting, most immediately, the Pine Ridge authoritarian government (which was both a byproduct and beneficiary of US settler colonialism). At the heart of their protest, too, was opposition to relentless encroachments by the US government on tribal sovereignty, decades of broken treaties, and opposition to the reservation system as a whole.

Japanese American activists observing the movement built upon recent involvement in the AIM occupation of Alcatraz. They also drew connections between the reservation system and their own community’s detention in concentration camps during WWII. As Merilynne Hamano wrote in her Gidra article, “From Manzanar to Wounded Knee,” in 1973:

“We cannot allow the kind of isolation and lack of support experienced by the Japanese Americans when they were ‘relocated’ into concentration camps happen to us or any other people again.”

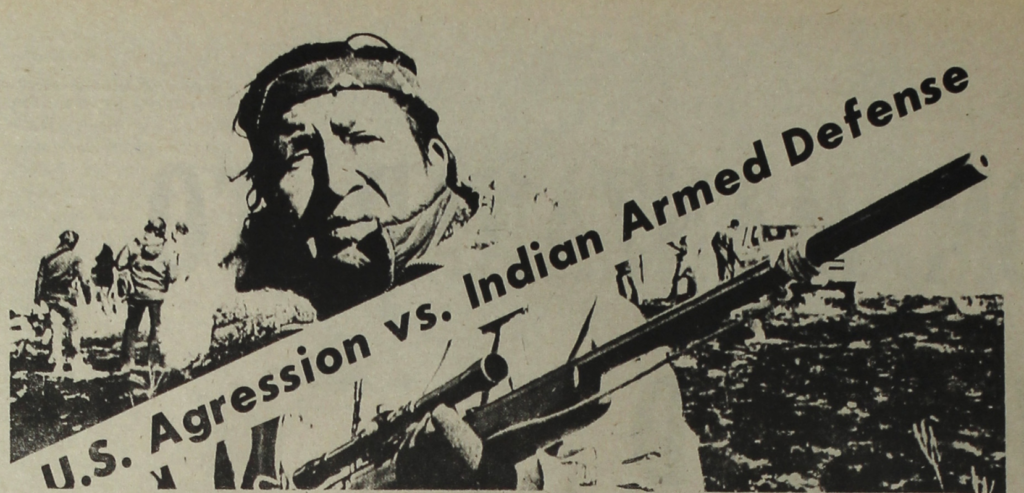

AIM activists and other allies – as well as elders, citizens, and grassroots organizers of the Oglala Nation – were armed with mostly shotguns and hunting rifles. They were met with FBI infiltration and an outsized response by US government operatives and Pine Ridge paramilitary forces with automatic weapons and armored vehicles.

Historian Karen Ishizuka writes about the Asian American delegation that traveled to Wounded Knee, and the connections they drew both to WWII incarceration and the US’s hyper-militarized invasion of Vietnam, in Serve the People. In the following excerpt from the book, which Verso Books has graciously allowed us to share, Ishizuka describes the role of Asian American activists in the action at Wounded Knee:

On April 20, 1973, fourteen Asian Americans surreptitiously left Los Angeles to support and bring attention to the Native American struggle at Wounded Knee in South Dakota. On Easter Sunday, representatives of the four races led a march from Crow Dog’s Paradise, the home of spiritual leaders Leonard and Henry Crow Dog, to Wounded Knee. Tatsuo Hirano was selected by the Asian American contingent as their delegate. The accompanying press release indicated, “According to the traditional medicine men of the Oglala Sioux, it fulfills the prophecy that when the four races get together, they will purify the land.” The release also pointed out the similarities of their histories: they too had been corralled into reservations euphemistically called “relocation centers” during World War II and watching their people shot on TV in old war movies and in present-day Vietnam.

Mo Nishida, who traveled ahead as part of an advance party, expanded the Vietnam analogy, saying that the route used to bring supplies into the besieged encampment in Wounded Knee was so dangerous it was called the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Kathy Nishimoto Masaoka said that, for security purposes, they had taken separate cars and different routes to get there from Los Angeles. Dennis Kobata recalled that as they approached the Pine Ridge Reservation they were stopped by a swarm of law enforcement and military forces. “A tremendous overkill,” he said, “it confirmed the perception of the American Indian Movement and other locals that it was like a war zone.”

The warriors of the rainbow on that Easter Sunday never made it to Wounded Knee. As the press release indicated, “The march was terminated on Wednesday, April 25, when 75 BIA men, Federal Marshalls and vigilantes confronted the group of 150 peaceful marchers with M-16s, sub-machine guns, grenade launchers and one helicopter.” Within the week, Cherokee supporter Frank Clearwater and “Buddy” Lamont, a local Oglala Lakota, would be shot and killed. After their deaths, seventy-one days of occupation, and reports of between 400 and 1,200 arrests, the siege ended.

–Excerpted from Karen Ishizuka’s Serve the People

Although the Wounded Knee occupation ended violently, its legacy lives on in new generations of Indigenous activists and allies. And some Japanese American survivors and descendants of WWII incarceration carry on the tradition of Indigenous allyship too. May Watanabe, a Tule Lake survivor who will turn 101 this year, spoke about her own expression of solidarity with activists at Standing Rock during her 2018 interview with Densho:

“I mean, we can talk about all the wrongs to us, but when you think about them… my girls laugh because when I was on the plane one time, we were flying over the Dakotas. And I just felt very emotional about those people down there trying to fight for their rights. And here we are, in this luxurious plane flying over them. I thought to myself, I’ve got to say something. I want them to think about this. And so I thought, I only have a few seconds, we’re about to land. [Laughs] So I stood up and I said, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, I have something to say. I just want you to realize that we’re flying over the Dakotas right now where [there are] these people who are being so wronged.”

Watanabe’s bold act is a reminder that Asian American and Japanese American solidarity with Indigenous peoples didn’t start or end at Wounded Knee – and that it’s needed just as much now as it was back then.

–

By Densho Communications and Public Engagement Director Natasha Varner featuring an excerpt by Karen Ishizuka from her book, Serve the People: Making Asian America in the Long Sixties (Verso Books, 2016)

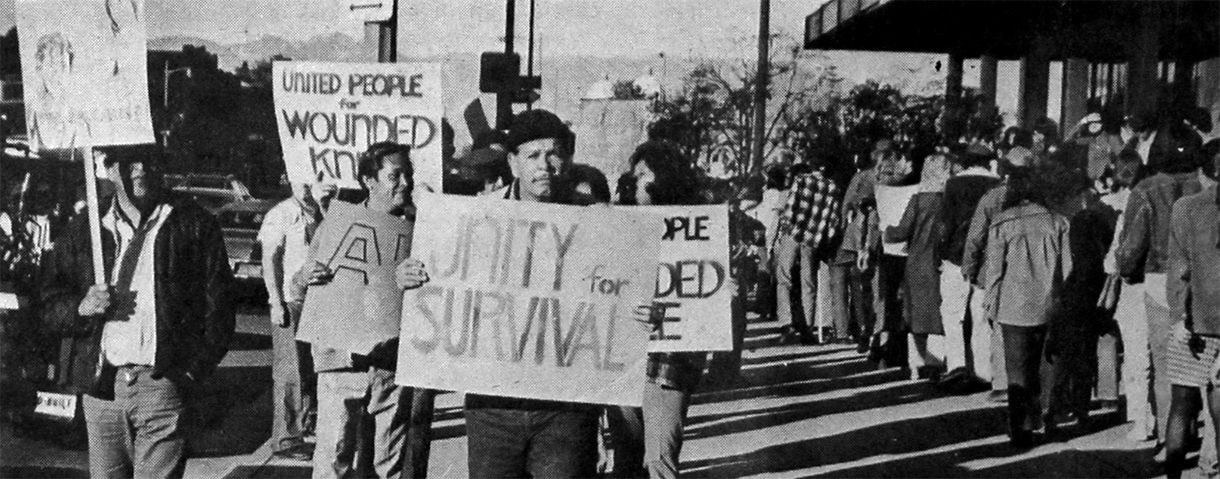

[Header image: Asians in Solidarity with Wounded Knee marched in front of the federal building in Los Angeles on March 8, 1973. Photo courtesy of Gidra, April 1973 edition.]