February 15, 2018

The immediate precipitating factor was the War Department’s decision to allow Nisei to join the army in a segregated unit that would become the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The WRA saw this as an opportunity to also separate the increasingly troublesome “disloyal” from the “loyal,” with the former to be segregated in a separate camp and that latter encouraged to leave the camps for “resettlement” in areas outside the restricted West Coast. (For a more detailed overview, see Cherstin Lyon’s Densho Encyclopedia article.)

The broad outlines of this episode—one of the most notorious in the history of the incarceration—are well documented in the historical literature. If you know a bit about the incarceration, it is likely you have some familiarity with this series of events. Here are some things about it you may not know:

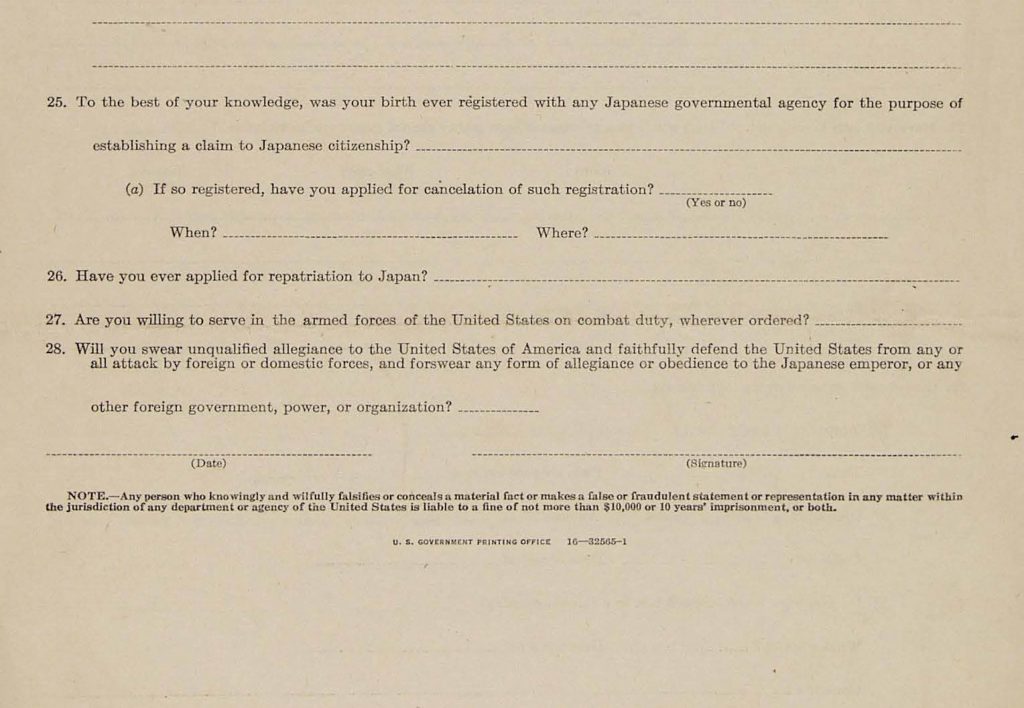

1. There were actually two different—but very similar—forms. Due in part to the dual purpose of the registration—for the army to identify Nisei men suitable for induction and for the WRA to identify “loyal” inmates who could be encouraged to leave the camps—each agency had its own form. Draft age Nisei men filled out the army’s DSS-304A, while everyone else filled the WRA-126. The forms asked for similar types of biographical information, and the key questions 27 and 28 were initially identical.

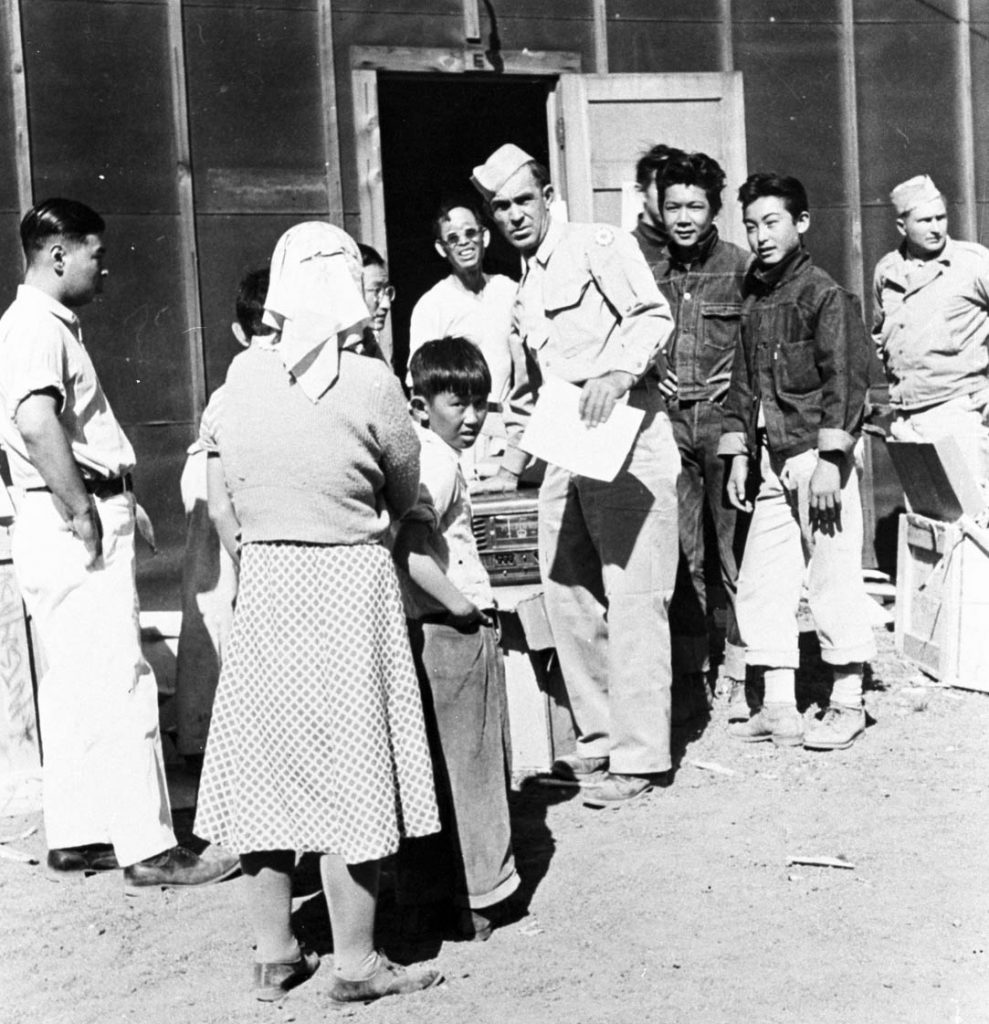

2. The army dispatched four-man teams to each of the ten camps to explain the purpose of registration, seek enlistments, and help administer the army’s questionnaire. Among those sent as part of these teams were a number of Nisei who had been inducted prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

3. A combination of army and WRA personnel administered the questionnaire in central areas of the camps. In Tule Lake, elementary and middle school teachers administered the questionnaire in block manager officers, with the “loyalty” related questions for Nisei men handled by the army team. At Gila River, registration was done in mess halls on a block-by-block basis.

4. Individual registration sessions varied greatly in time. Charles Kikuchi wrote that his took only fifteen minutes, since he had filled out most of the from beforehand, and he was clear in his own mind as to how he would answer questions 27 and 28. But sessions for others who were less prepared took hours.

5. Some level of resistance to registration took place at every camp, whether informal or individual or more organized. Issei and Nisei organized separately at Topaz, with the latter boycotting registration until their concerns could be addressed. Unrest at Tule Lake led administrators to arrest and remove those it considered agitators.

6. Japanese sections of newspapers at Topaz and Gila River published stories that criticized registration, which broke from the official policy that these sections just publish translations of stories in the English sections.

7. It took a long time to finish registration. The first announcement of what was to come came on January 28 with the announcement that Nisei would be allowed into the army and that the War Department would send representatives to the concentration camps in two weeks. Registration in the camps started around February 10. Due to various levels of resistance, registration started late in most camps and stretched on for over a month in many.

8. The response to the questionnaire varied greatly from camp to camp. At Tule Lake, 42% did not answer questions 27 and 28 or answered “no-no”; at Minidoka and Amache, the figure was less than 3%.

9. In the end, only 805 men in the ten camps volunteered for the army. By contrast, 4,414 male Nisei initially answered “no” to question 28 with another 715 giving a qualified answer.

10. The questionnaire led to a large increase in requests for repatriation/expatriation: from just 52 in January 1943, there were 987 in February, 972 in March, and 1,514 in April.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

For more on this episode, see Eric Muller’s American Inquisition: The Hunt for Japanese American Disloyalty in World War II (University of North Carolina Press, 2007) and Cherstin Lyon’s Prisons and Patriots: Japanese American Wartime Citizenship, Civil Disobedience, and Historical Memory (Temple University Press, 2011), among other works. Statistics come from the WRA’s own statistical summary, The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Description (U.S. Department of the Interior, 1946).

[Header photo: Original WRA caption: People from the Manzanar Relocation Center were moved to the Tule Lake Segregation Center and quartered in the ten blocks which had been built as an addition at Tule Lake. They arrived in four special trains and were taken directly from the railroad to their new homes. A total of 1876 people came on the four trains. They were tired from their long train ride, but everything was done to make them comfortable and aid them in getting settled. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]