CAMPU: Episode 1 “Rocks” Transcript

Keep scrolling to read the transcript, or download a copy here.

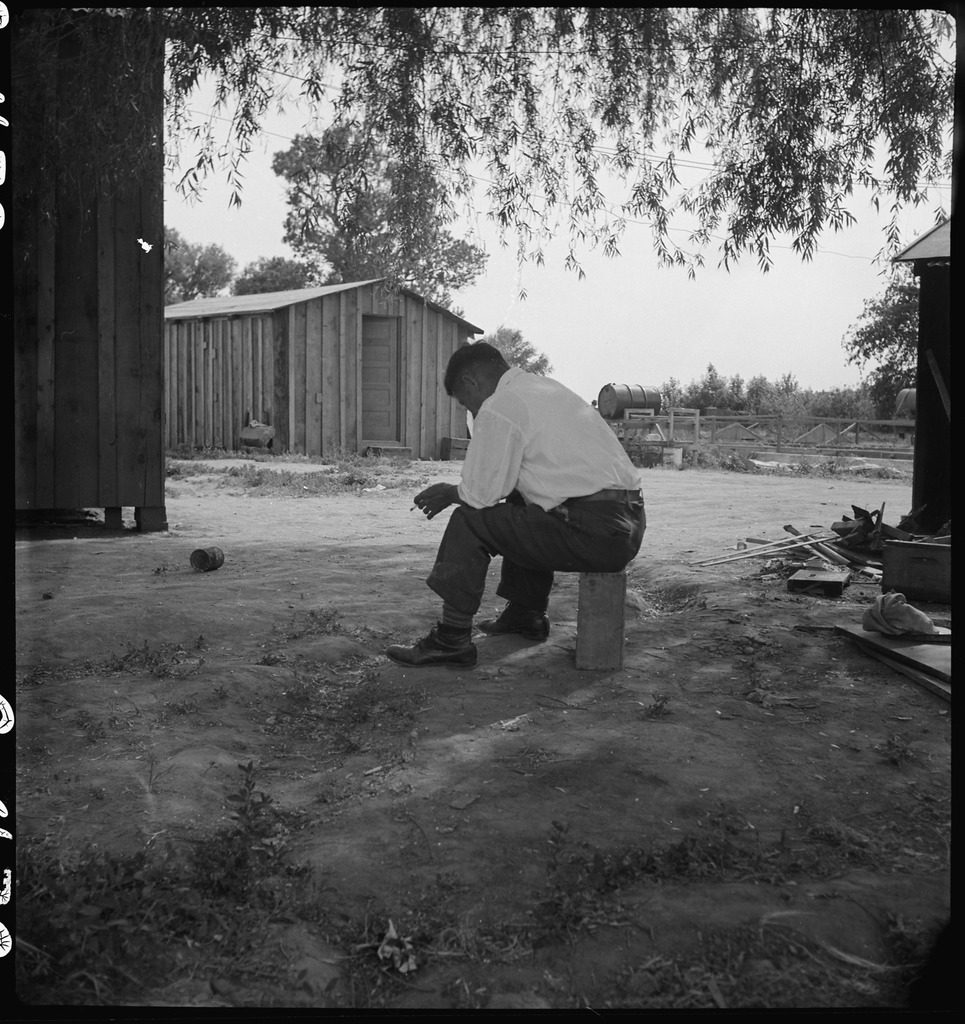

VO: Seiichi Tsuji was finally leaving. Not that he really had a place to go. For three years behind barbed wire, Seiichi received a train ticket to wherever he wanted, shipping for whatever belongings he had left, and twenty-five dollars. He’d lost, among other things, the car, the tractor, and the farm where he’d raised four children and buried another.

Kiyo, his oldest, left camp first—in September 1943. Kats, his second, left next in June 1945. Seiichi was gone a month later. His wife and two youngest stayed behind, but they would follow soon.

VO: Like most of the people who were leaving, he didn’t have much anymore. Still, during his last few days at Heart Mountain, he fashioned scrap wood into boxes. Packed them with care. Hammered them shut. They were so heavy the soldiers could barely lift them onto the truck. ‘It feels like rocks,’ one of them complained.

He was right. When Seiichi’s wife asked him why he had packed crates of rocks, he told her he thought they were beautiful.

Theme.

VO: From Densho, I’m Hana Maruyama and this is Campu.

End theme.

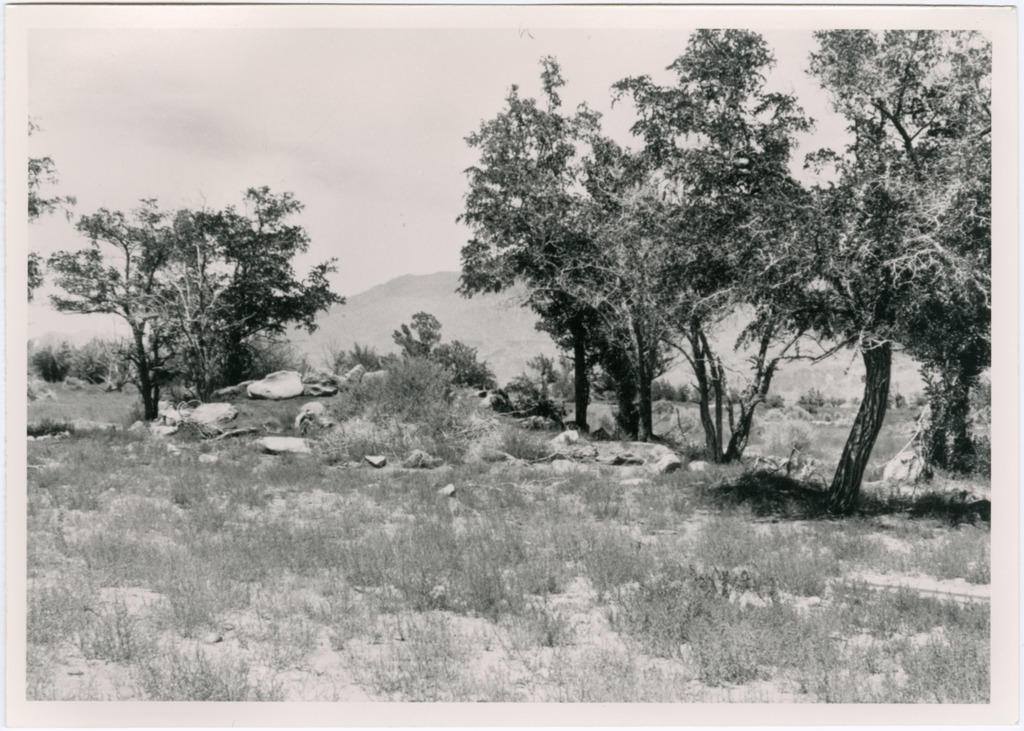

VO: In this episode, we talk about rocks, memory, and unanswered questions. My great-grandfather, Seiichi Tsuji, or Jichan as we call him, was our inspiration for this episode. But to talk about Jichan’s rocks, we should first talk about where they came from.

VO: In the northwest corner of what we know today as Wyoming, there is a mountain. The Apsáalooke—more commonly known as the Crow—call it Foretop’s Father. Here’s Dr. Janine Pease, speaking in a recent panel on Japanese American incarceration on Indigenous lands.

JANINE PEASE: Foretop’s father is a mountain where we find … the connection the Apsáalooke have with all of the cosmos, nature.

VO: We know it as Heart Mountain. It’s about 8,000 feet tall, standing in the middle of otherwise flat plains. The rock it stands on is fifty-five million years old—ancient, at least by our standards. But Heart Mountain itself is more than five times older. It’s hard to grasp the sheer scale of it. The rock that makes up Heart Mountain has been here for more years than there are seconds in a human life, for the whole lifespan of our species, a hundred and sixty-seven times over.

Geologists believe the mountain was originally 25 miles to the northwest, part of the Absaroka range. The mountain moved here somehow—it was the largest rock slide known to humanity.

How does a mass of limestone heave itself over rock 250,000 years younger? How did so much rock slide so far across the plains? Was it a volcanic eruption, an earthquake? Did it happen slowly, over the course of several millenia? Or, as the current theory goes, suddenly, catastrophically, in less than thirty minutes?

Scientists have been trying to figure out what happened for the last hundred years. One team of geologists called it a “long-standing enigma regarding its emplacement mechanism.” Basically, they don’t entirely know what happened.

But the Apsáalooke know.

PEASE: the Apsáalooke creator, [Apsáalooke] sought the people to find through a great migration of perhaps as many as 30 or 40 years looking for the best place—exactly the right place for the Apsaalooke people to live. … finally coming to the foothills of the Bighorn mountains in what’s now Wyoming.

At that point, in the way in which we know it, the stars fell, on a particular blessed night, they fell on to plants and the plants were seen as tobacco, a sacred plant. And in this way, the Apsáalooke identified the blessed place, the Big Horn mountains.

VO: In 1851, the U.S. divvied up the area between eight Native Nations, attempting to draw neat borders where none had existed previously. In this treaty, 33 million acres were designated for the Apsáalooke.

By 1868, less than twenty years later, that land had been reduced to 8 million acres. Part of the land the federal government took this time? Heart Mountain. In 1905, it took an additional 5 million acres. The reservation was now one tenth of its original size. The Apsáalooke are still struggling to regain access to these lands today.

PEASE: And it happens that over the last 15 years, the Apsáalooke people have been returning to Foretop’s Father … to talk about and recall powerful stories of our relationship with the place. … the leader of the return to Foretop’s father, is Grant Bulltail, an elder from [Apsáalooke] or Pryor district. … some 30 families go there every year.

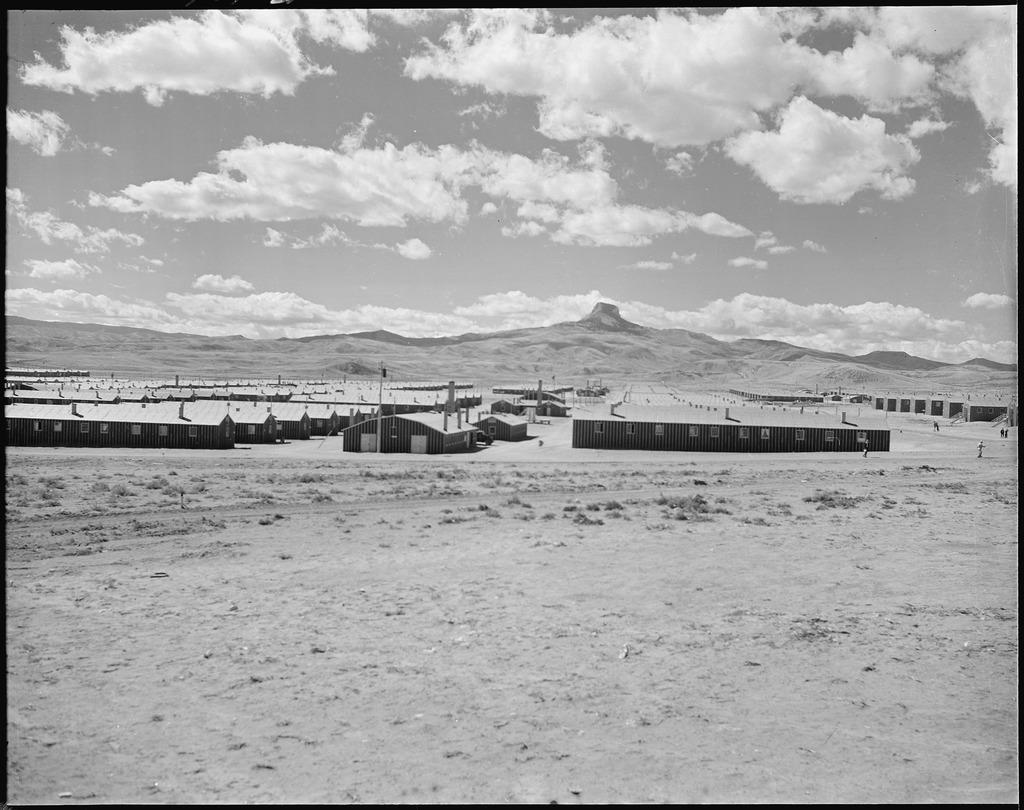

VO: Back in summer of ‘42, a big ruckus had begun in the shadow of that mountain. Contractors hired locals to build barrack after barrack. They got so good at building these structures that the crews bragged they could put one together in under an hour. Most of the workers were white settlers, but some, Dr. Pease says, were Apsáalooke.

PEASE: During the construction of the Heart Mountain Center, there were a number of Crow Indian men who were involved in the construction crews. My own father was in the construction crew, and he said he didn’t have any idea what they were building. He was 19 years old. … he always felt really sad in his later adulthood that he had participated in building that center. But he didn’t realize as a 19 year old, what it was that they were building.

VO: Nearly seventy-five years after the Apsáalooke had been forced from Heart Mountain, 14,000 people of Japanese ancestry would be forced to that same place, Seiichi and his family among them.

MITS KOSHIYAMA: I think Heart Mountain was mostly Los Angeles people, and a big percentage Santa Clara valley people, and a sprinkling of San Francisco and Washington.

VO: In all, 120,000 would be forcibly relocated from “strategic areas” all over the West Coast. Big cities—

ROY DOI: Sacramento.

JIM AKUTSU: Seattle.

EMI SOMEKAWA: Portland, Oregon.

AMY IWASAKI MASS: Los Angeles.

JOAN RITCHIE DOI: Los Angeles.

FRANK EMI: LA.

DOI: in Boyle Heights.

HAL KEIMI: Hollywood.

EMI: on Beverly and near Vermont.

MITS KOSHIYAMA: In the heart of Mountain View.

VO: And nowhere near a city.

LAWSON SAKAI: —a little town—

DOI: —a small town—

JIM HIRABAYASHI: —little village—

SUMI UYEDA: —little town of Penryn—

SAKAI: —Montebello.

DOI: —Loomis.

HIRABAYASHI: —Thomas.

VO: As scary as camp was, it was also—in a word—boring. Incarcerees had to find ways to pass the time.

TOM MATSUOKA: nothing to do, you know—everybody nothing to do. All of a sudden—I don’t know who started—

KAZUKO UNO BILL: the main activity was to polish rocks.

HENRY SHIMIZU: he went along the riverbed and picked up rocks.

LILY C. HIOKI: He collected these rocks and he polished them—

MATSUOKA: By gosh, that thing is really came popular, something to do in the camp.

NANCY K. ARAKI: you’d find a lot of flint stones …

BILL: some beautiful agates,

ARAKI: arrowheads

BILL: all different colors,

HIOKI: big ones and little ones.

SHIMIZU: … so many big rocks that friends built him a wheelbarrow so he could bring it in …

BILL: they were really beautiful.

HIOKI: They were works of art.

MATSUOKA: You picked a rock, go to the bathroom, then bathroom there is concrete cement so we polish the rock on the cement. Then they gave us blanket. You polish with the blanket.

VO: Clearly, Seiichi wasn’t alone in collecting rocks in camp. It was a particularly popular pastime for Issei, or immigrants. One, Suikei Furuya from Hawai‘i, even wrote several haiku about rock collecting in camp. While people of Japanese ancestry in Hawai‘i were not rounded up the same way they were on the West Coast, some 2,000 were incarcerated—first in Hawai‘i and later in the continental U.S. Here’s one haiku Furuya wrote at Camp McCoy in Wisconsin: “We were sent faraway / and within the fence / I gather pebbles.” And rocks weren’t the only thing incarcerees collected.

TOMIKO HAYASHIDA EGASHIRA: scrap wood.

HATSUKO MARY HIGUCHI: ironwood from Poston

ELAINE ISHIKAWA HAYES: something called tule grass,

EGASHIRA: finding sagebrush or mesquite out in the desert—

MANY: Shells.

PEGGIE NISHIMURA BAIN: People would go out—

FUSAKO YAMAMOTO: —and they’d gather the shells—

BAIN: —they’d dig four feet down, they’d get … way up to their waist.

HAYES: And then they made—

YAMAMOTO: —pins,

BAIN: corsages, birds—

YAMAMOTO: ornaments—

BAIN: Picture frames—

HAYES: —out of these white shells.

VO: People would make things out of whatever they could find.

HAYES: the women … made offering plates out of the tule grass, wove them into kind of flat plates.

EGASHIRA: —making a cane or maybe a table.

BAIN: If there’s nothing around, somebody is gonna get smart and make use of what’s available.

VO: My great-uncle Kiyo said the practice of collecting things was so widespread it had a name—“Campu No Kuse,” or camp custom.

[subdued musical cue, solo piano]

VO: Camp, or campu, as it was transliterated by the Issei immigrant generation, is a word that carries a lot of meaning for Japanese Americans. It carries all the times we have been told not to call it a concentration camp—even though that’s what FDR called it.

VO: The word “camp” is a question that the children of the incarcerees learned not to ask. It’s the moment they realized that camp and summer camp were two very different things. It’s everything the incarcerees wanted to tell their children, but couldn’t.

Campu carries the everyday acts of translation that Issei undertook, and their efforts to navigate a country far from the one where they had been born. We call this podcast “Campu” in recognition of the Issei, many of whom died without leaving records of their voices. We’ll be working their words in where possible, but since our great-grandparents’ first and sometimes only language was Japanese—this can be a challenge.

[end cue]

[build music and fade/cut to next line]

VO: How did it all begin?

HOMER YASUI: Well, let’s talk about Pearl Harbor.

FDR: Yesterday, December 7th, 1941, a date which will in Infamy—

[sound distorts at the end of the quote]

VO: But that wasn’t really the beginning.

[VCR rewinding sound, then stop and playback.]

[Minimalist musical cue. Pads, arpeggios.]

GEORGE WAKIJI: It was longterm. It didn’t start just with the war.

JAMES YAMAZAKI: … the war was going on in Asia, and the local situation of the anti-Japanese feeling was getting stronger. And in ’37, Japan was in turmoil, and … bombed the U.S. naval ship Panay and actually sunk it, I think. And it looked like reason for war then, but it didn’t happen.

[rewind]

MIYAMOTO II: there was a lot of sentiment against the Japanese people on the grounds that these are people who are going to come in and overrun the country with their high birth rate and with their aggressiveness and so on.

TSUGUO “IKE” IKEDA: our parents could not vote. They couldn’t become citizens of this country, by federal law, which was ridiculous in a democracy.

[rewind]

FRANK MIYAMOTO: The Immigration Act of 1924,

IKEDA: where persons of Japanese ancestry were not allowed to come to this country,

MIYAMOTO: stopped the immigration into the United States—

VO: Here’s Dr. Erika Lee, University of Minnesota history professor and author of America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States.

ERIKA LEE: By the 1930s all Asians are effectively barred from migrating to the United States and they are prohibited from becoming naturalized US citizens.

MIYAMOTO II: It was a sign to the Japanese people that the American people really … did not accept the Japanese as equals.

[Second cue: more foreboding. Ostinati on strings.]

HIRABAYASHI: Initially, the alien land law was passed in the state of California in 1913. I think the other states passed similar laws because they didn’t want Isseis coming from California into their states.

VO: The alien land laws targeted immigrants ineligible for citizenship—in other words, Asians, who had been prohibited from becoming citizens by a series of Supreme Court decisions. These laws made it illegal for Asian immigrants to own land or sign long term leases.

KARA KONDO: … soon after the anti-alien land law we had to move from our property.

WAKIJI: Being a non-citizen, he was an alien, my father was not able to own property.

VO: There was also the issue of how much Asian workers were paid.

ERIKA LEE: So Asians were never paid the same or equal wages for the same work as white workers. And they were often just shunted into … certain economic positions where there was no ability for economic mobility, and they were excluded from professions. And this is just one of the ways in which again, our capitalist system has relied upon an exploitable source of racialized labor to quote unquote develop the United States.

VO: And then there was the mundane, everyday prejudice individuals encountered.

YAMAZAKI: …one was when I was still a young teenager, I went to the Ambassador Hotel, which was the biggest hotel in town … And I put on a clean shirt and tie and all that, and … this was just a job as a porter, or some menial job, I’d do anything just to have a job. I was shown the back door and told just to remove myself from the premises.

EMI: the team goes swimming in the public pool and because you’re not white, you’re sitting up in the benches watching your scout mates swim and you can’t.

YAMAZAKI: And somewhere along the road, we brought up the subject that the country didn’t want us.

VO: At one point though, Japanese laborers had been seen as the desirable replacement for unwanted Chinese laborers. How did we get to this point? Here’s Dr. Lee:

LEE: The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first time in our nation’s history that the federal government singled out a group for immigration exclusion based on race but also on class. It barred Chinese laborers. … It was supposed to be only in place for 10 years, but it ended up being the law of the land for 61 years. … There were tens of thousands of Chinese who came in in 1882, before the Exclusion Act was passed, but by 1887 were only in the double digits.

YASUI: So the railroad magnates … they hired Japanese laborers to come over, and that’s when the immigration really took off for the Japanese in Oregon. In Hawai‘i, it was earlier. In California, it was a little earlier.

VO: But soon, white workers’ groups, angry now at Japanese immigrants for the perceived theft of their jobs, began to target them as well.

MIYAMOTO: … there was the point at which, my mother tells me … the white workers of the mill tried to run the Japanese workers out of the area … she said one night my father sent her … away from the sawmill town to another place so that they might not get hurt and he remained, insisting that he was not going to be run out by a bunch of rowdies. … they finally moved out.

KONDO: our front porch was set on fire. … there were about … four or five bombings of … not the residences, normally, but generally some structures that were on the farms. And they were not devastating … but enough to do some damage and, of course, to frighten people.

MIYAMOTO: … once we moved in, however, especially rowdies, vandals, would make it unpleasant for us by throwing junk on our front porch and this sort of thing.

VO: It would be a mistake, though, to blame workers’ groups without also holding the corporations and politicians who fostered and encouraged this anti-Asian prejudice accountable. By the early 1900s, says Dr. Lee,

LEE: Japanese and Korean laborers are such an important part of the plantation workforce and are heavily recruited and … become indispensable. But as they become indispensable … they begin to organize and as they flex their economic power, plantation owners seek to disempower them by introducing additional laborers, this time from the Philippines and from Korea to break Japanese labor unions’ hold on the plantation economy.

VO: Sound familiar? That’s because something very similar had happened in the 1870s with Chinese workers.

LEE: By the 1870s, the anti-Chinese movement, led not only by the working men’s party, but also really again supported and promoted by professional politicians, has become a major political movement that national politicians cannot afford to ignore.

[VCR pause.]

VO: Which is how we end up with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. But that’s not really the beginning either.

LEE: With slavery and settler colonialism it’s about the management … of certain populations towards the service or in the service of a white settler nation. So we know that the slave codes and the forced exile of Native Americans is part of this management to control where people go, what rights they have and to keep certain opportunities—the best opportunities—for white settlers.

VO: Chinese exclusion, alien land laws, the 1924 Immigration Act, Japanese American concentration camps—all of these were part of that same system of management of people, land, and labor.

[Fade out music.]

VO: And on and on. There aren’t any neat beginnings and endings in history. Each layer builds on the one below, mixes with it, sometimes slides up and over layers 200 million years younger.

LEE: So one of the things that I think is so important when studying Asian American history is not only understanding, you know, where did Asian Americans come from, how did they come? … But also, what was the world in which they entered, you know, they did not enter into a vacuum. There were already existing racial hierarchies and institutions and worldviews that directly impacted how they came, what kinds of freedoms they did have compared to others and which ones they didn’t.

VO: Hopefully, this very short dive into history has given you a rough idea of how deeply embedded some of these social structures—race, capitalism, settler colonialism—really are. Sometimes they can feel insurmountable, “set in stone.” But if Heart Mountain has taught us anything, it’s that even mountains can move. History, like rocks, pokes up out of the ground if we know where to look for it.

Sometimes we walk by it. Sometimes we stop to admire it. Sometimes, we pack it into boxes and take it with us.

What can Jichan’s rocks tell us about the incarceration? About what the incarcerated lost? About how these places both tormented and comforted them? What can rocks tell us about what we—as Japanese Americans—still carry?

Dr. Donna Nagata, a professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, does research on Japanese American concentration camps and intergenerational trauma. She says that trauma manifests differently depending on the age incarcerees were in camp.

DONNA NAGATA: the Issei really were suddenly cut off from their livelihoods that they really had been developing over decades since arriving in the US. They’d established families, livelihoods, were making this their new home. … they were really in an impossible position. Their home country—where they still had many relatives and sometimes their children were living and being educated there—had now been declared an enemy of the United States. So being classified as enemy aliens, they had no rights, at the same time that they were actually prevented from becoming US citizens. So really in a bind there.

VO: We’re going to be talking a lot about generations in this podcast, so we should pause here and go through the terms Japanese Americans have for the different generations. Issei means the immigrants. Remember earlier when we talked about the Immigration Act of 1924? That meant that for the most part the last Japanese immigrants arrived in 1924. So, by World War II, the Issei were mostly adults, often middle aged or older. Nisei, or the second generation, means their children.

NAGATA: Unlike the Issei parents, the Nisei were U.S. citizens and had been born and raised here. Yet at the same time, they were being treated like enemy aliens, just as their parents were without any regard to their constitutional rights.

VO: When they were in camp, most Nisei were young adults, adolescents, or even children.

NAGATA: And those are critical stages of identity development. So the incarceration was a powerful communication to them, about how the US viewed their status in this country.

VO: Sansei, or the third generation, means the children of the Nisei. Some Sansei were born right before or even in camp, but the majority were born after the war. So Nisei were often parenting Sansei in the aftermath of their experiences in camp, and this absolutely impacted their parenting styles.

NAGATA: the vast majority of Nisei did not talk openly about what they had been through or how they felt about it.

I do think a lot of that was done to protect their children from hearing the negative experiences that they had been through. I also think that part of that was their own need for themselves to move on and not dwell on the negative experiences for themselves.

VO: Or, maybe they did talk about it, but only as a passing mention, or a funny anecdote.

NAGATA: the Sansei … knew that they couldn’t ask more questions. The nonverbal communication was ‘this was off limits. This is not something that you need to be digging into, and we don’t really want to discuss it.’

VO: Could sansei experience trauma from something they had, for the most part, not actually lived through? Something that in some cases, they knew very little or nothing about—because of the silence surrounding that experience?

NAGATA: One of the interesting findings from my research showed that Sansei respondents who had had a parent in camp or significantly less confident about their rights in the US than those sorts who had not had a parent who was incarcerated. … There were also sansei who were driven to, in some ways compensate for what their parents had gone through. So they wanted to fulfill lost dreams and aspirations.

VO: But that inheritance had its silver linings.

NAGATA: they also picked up resilience and saw their parents and grandparents as really powerful role models.

VO: Still, many Japanese Americans who had family in the camps will understand me when I say that silence can take up a lot of space.

NAGATA: I think silence itself is a really powerful transmitter of trauma. So the avoidance of something that is significant, really signals that there’s unfinished business…

VO: At the end of the day, the silence means that we only see the vague outlines of the trauma the incarcerees faced. Here’s Peggie Nishimura Bain. 63 years after she left camp, she said,

BAIN: I still have nightmares. I have nightmares quite often, trying to decide, “What am I going to take? What am I gonna do with everything? What’s going to happen to us?”

[Music cue: Burning]

VO: Every family that endured the incarceration has a story about the things they brought with them and the things they had to leave behind. The stores, the homes, the farms, the treasured piano they sold for pennies on the dollar. The family photos and histories that parents burned for fear they would be taken as proof of their loyalty to Japan.

AKASHI: … we came back from church, and my father was there, and he says, “Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.”

HERZIG-YOSHINAGA: —rumors spread that if the FBI came to your home and found Japanese language books, your father or uncle, or mother would be taken away and fear just gripped the community—

AKASHI: He had a bunch of documents and things like that, and he says, “Help me burn ’em.” … Pictures, newspaper articles, anything that related to Japan, he burned ’em.

NAKAO: My dad says, “Get rid of everything,” so we just burned things, buried things, broke things up, did everything to get rid of all the things that Grandma sent from Hiroshima…

HERZIG-YOSHINAGA: My father destroyed almost all of his Japanese language books, including a book that he had written—he had a number of copies of an autobiography my sister said he had written. [s5]

RICHARD MURAKAMI: Lot of people they have memories, photos from before, but we don’t have those things, so that’s one of the things I miss.

[end cue]

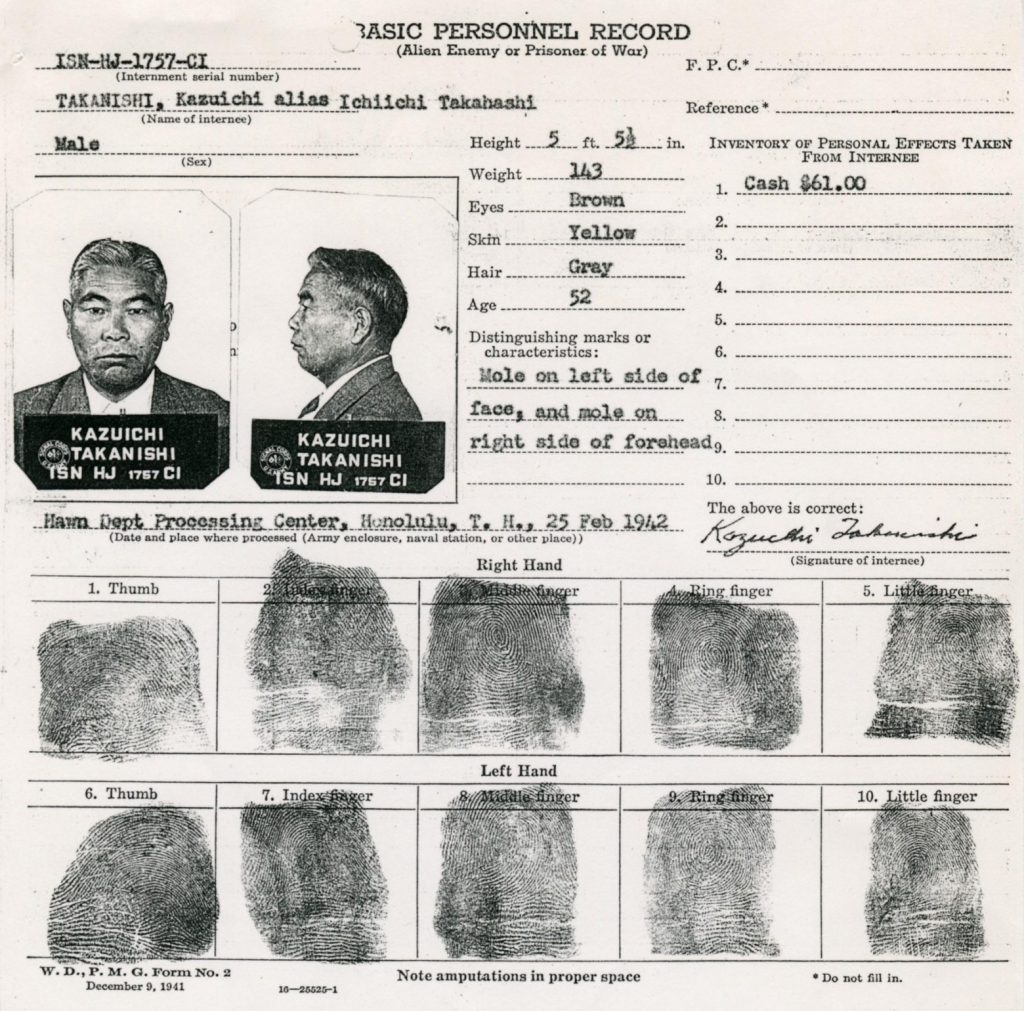

VO: As though the U.S. needed anything more than their race to link them to Japan. Some were arrested with nothing but the clothes on their backs. No time to get dressed, to pack even a toothbrush. No time to say goodbye to their families. They often had no idea where they were going.

FRANK S. FUJII: one hour after Pearl Harbor now—

BILL: about midnight—

JAMES OMURA: still dark … before 6 o’clock—

GLORIA KUBOTA: ten days after, I guess, my son was born.

BILL: —there was a knock on the door.

OMURA: —there was a knock on the door.

YASUI: and within a matter of days,

DONALD TAMAKI: FBI swept through the community and arrested—

YASUI: —1500 Issei—

TAMAKI: —community leaders,—

YASUI: almost exclusively … men, although fifty women were also rounded up in that first roundup.

OMURA: When I opened the door—

BILL: there were these three big men—

FUJII: Two big white gentlemen—

OMURA: I could see only one man … it was so dark I couldn’t see but there were three other men behind him.

BILL: they kind of pushed open the door—

GRACE SUGITA HAWLEY: —ransacking the house, and they were tearing through the Shinto shrine—

BILL: and then they asked where my father was—and he was already in bed—

KAZUKO NAKAO: They just said, “You’re coming with us,”

TOM AKASHI: —handcuffed him, put him in a car, and took him away—

YASUI: he was picked up … Friday, and of course, that’s a school day. So when … I … came home, my father was gone and—

NAKAO: he couldn’t pack anything—

BILL: And I said, “Where are you going? Where are you going?”

OSHITA: … my mother drove us out, and there were a lot of buses, and … some of them were already moving on, and we just yelled from where we saw a bus full of men … and I was the only one yelling, “Otousan.”

Nobody called their father Otousan. Nobody called their father Otousan. You know, ‘Papa,’ ‘Mama.’

But we missed him. … There was this Mr. Yamashita, a very good friend … he pointed … ‘Your dad’s gone already.’ … And the first letter my father wrote to us, he did say, … “I heard your voice, Grace, I heard you.”

MINORU TAJII: I never saw my father—

FUJII: —for three and a half years.

RICHARD IWAO HIDAKA: for two and half years—

TAJII: —how many years.

FUJII: He was shifted constantly from Missoula, Montana, to Bismarck, North Dakota—

COOKIE TAKESHITA: to Crystal City, Texas,

HAWLEY: to Sand Island.

FRANK SUMIDA: to Lordsburg

FUJII: and ended up in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

AKASHI: Boom, gone. … no goodbye, no nothing. Just gone.

[muted panic in the music cue]

VO: Then on February 19, 1942, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, paving the way for the forced removal and incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. Most had a couple weeks to prepare, but some had as little as 24 hours.

TAKETORA JIM TANAKA: We had ten days. ….

GEORGE YOSHINAGA: About a week before… we didn’t have that much notice, you know…

TAKETORA JIM TANAKA: It was better than … some people, they had forty-eight hours. Worst one was, I don’t know if you ever heard about it, at Terminal Island they had twenty-four hours. I talked to one fellow, I couldn’t believe it. Twenty-four hours.

VO: Families had to figure out what to sell, what to store, what to bring with them, what to leave behind.

TED NAGATA: many people lost their homes, their cars, their business, their furniture, their bank accounts.

YOOICHI WAKAMIYA: —two, three acres of crops—

WAKAMIYA: … he had to abandon it. What can you do? You can’t take it with you.

NELSON TAKEO AKAGI: So $20,000, so we sold it for one-tenth of the value—

SUMIDA: —a ten thousand dollar restaurant. Never compensated. Not a penny.

YAMAUCHI: We didn’t own it, we were just renting, we couldn’t take anything.

BOB UTSUMI: —main business was weddings, funerals, family pictures, portraits, passport photos. … he was an “enemy alien,” he had to turn in his cameras and essentially put him out of business.

YOSHINAGA: All my personal things like my bicycles and my sporting equipment.

SALLY KITANO: a beautiful doll, and it was a brand new one I had just gotten from Santa Claus.

EMI: a 1934 Chevy coupe which was a pride and joy.

HERZIG-YOSHINAGA: he had been carrying around the ashes of one of my sisters, a half-sister, and my mother told me many, many years later that he had buried those ashes in the backyard of our home in Los Angeles. … I’ve often thought of going back to that house, but I didn’t know how to …approach the occupant of the house to ask if I could dig up his backyard to look for the ashes of my sister my father had buried fifty years ago. So I’ve never done it.

[end cue]

VO: Of course, just because they managed to store something didn’t mean it would still be there when they got back.

TATSUNO: —we rented it to them, and they seemed like a very nice couple and they came to Tanforan—

TATSUNO II: —they had broken in, broken into the back room, they had broken into the basement, they even drove our car to Los Angeles.

TANAKA: … what good is it? The cop would look the other way, they come vandalize, take what they want, … they burn the barn down or shed down or whatever. But that’s how it goes.

SUMIDA: —they were waiting out the door for us to go to camp. The minute we went in camp, they just go right in there and steal everything. They won’t buy it. They knew we were going into camp, so why buy it when they could get it free?

VO: The lucky ones got to choose what to bring.

YAMAUCHI: … they said that we can only take one suitcase per person.

NAKAO: Dad went to town and bought eight suitcases, we all had one suitcase apiece.

OMOTO: We were told we could only take what we could carry, and that wasn’t much because I had three younger sisters.

KITAKO IZUMIZAKI: …they all said, “Oh, you guys better buy boots, ’cause I think we’re gonna be sent to a desert, and there’s rattlesnakes.” So we all bought cowboy boots. [Laughs]

VO: They chose carefully, but many had no idea where they were going or what to pack.

OMOTO: … my father thought that Niseis and Isseis would be separated. … he went and bought tin plate, tin cup, and a silverware for each of us to take in case. And then Mom made a money belt and wrapped up so we could tie it around our tummy and gave each of us cash, so we’ll have something.

IZUMIZAKI: … my suitcase was full of sanitary napkins.

NAKAO: we wore a lot of clothes. [Laughs] It was a beautiful day in March, and my goodness, I had my wool suit on, and wool coat on, and my hat on and good shoes.

… we really didn’t know what we needed.

[pause.]

VO: Most were sent to 15 temporary “assembly centers,” where whole families lived in hastily built barracks if they were lucky—and horse stalls and other animal pens if they weren’t. Later that summer and fall, they were shipped off to ten “War Relocation Centers”—Manzanar, Poston, Gila River, Granada, Heart Mountain, Jerome, Minidoka, Rohwer, Topaz and Tule Lake. They spent anywhere between a few months to four years in those camps.

And then, in January 1945, Japanese Americans were finally permitted to return to the West Coast.

TANEMURA: my father was given only $14 at the time, to leave camp.

UTSUMI: I got my train ticket and twenty-five dollars—

TANEMURA: —so I remember boarding a bus, and we got to this bus terminal—

UTSUMI: —got on a train by myself, one small suitcase—

FLORA NINOMIYA: the train was very, very crowded. It was very, very hot.

VO: Some people had homes to return to, others tried their best to make arrangements.

UTSUMI: The church became a hostel, and they had laid out a bunch of bunks, cots, mattresses… They did have a shower back there, and a pretty nice big kitchen. … And we stayed there for quite a while.

KEIMI: … a junky looking trailer … it was our home for a few months.

YANO: my mother and my father had several friends who were … they were homeless. They didn’t have a place to go back to. … so my parents allowed them to come and stay with us. … My neighbor who used to live next to us in Topaz … And then Mr. and Mrs. Ueda and her daughter lived at my mother’s house for several years.

TANEMURA: And this friend … was able to find housing for us at the Japanese Language School.

MAKO NAKAGAWA: That was the first time I remember Mom and Dad arguing is what we should do out of camp and when should we leave.

VO: Once again, they had to choose what to bring and what to leave behind.

FUMIKO HAYASHIDA: We didn’t bring the crib back … we kinda wanted to bring it home but, it was all wood and … Too much trouble packing and, we left it.

KEIMI: I don’t recall how we got the dog in Heart Mountain, but it was a cocker spaniel, we had it in Heart Mountain, and somehow my folks got it shipped and we had the dog there in that trailer camp.

HENRY MIYATAKE: Harry Kadoshima’s father made this huge … replica of the water tower. And they … brought it home from the camp. And it’s a … huge thing.

VO: Some had new reminders of the war etched onto their bodies, like the Nisei who volunteered or were drafted from the camps, often leaving family behind barbed wire.

TOSH YASUTAKE: when you get hit by shrapnel, it’s hot enough that it’s sterile when it goes into the wound so you don’t have to worry too much about infection. And so they usually leave it in there. And I still have it in there.

VO: And then there was Seiichi, who packed boxes of rocks. But maybe that wasn’t so strange. In camp, rocks often became the monuments that marked incarcerees’ landscapes and lives. At Manzanar, the ruins of rock gardens remained long after the camp had closed.

GEORGE IZUMI: There was a fellow named, I think his name was Mr. Kato, he was a rock garden specialist.

ARTHUR OGAMI: My father … he’d go out to the foothills of the mountain to pick up rocks, trees, shrubs to use in the garden.

IZUMI: —he built a beautiful rock garden up near the hospital.

FRANK ISAMU KIKUCHI: they had water channeled in and they had all kinds of beautiful flowers, they had rocks forming the beds—

VO: Some of these rock gardens followed centuries’ long traditions. Yoko Kawaguchi, author of Japanese Zen Gardens, says these traditions go all the way back to the seventh century in Japan.

YOKO KAWAGUCHI: you know, in the West, you think of gardens and you think of plants, but in the Chinese, Korean and Japanese traditions, … they may include plants, but the important thing was always to create a landscape and plants are are only a part … of that landscape. And the rocks were essential to create the outline of that landscape.

VO: Though rocks figure centrally in these gardens, the term ‘rock gardens’ is actually a bit of a misnomer.

KAWAGUCHI: at Manzanar, actually, they are pond gardens. And they use rocks a lot in the pond gardens there.

VO: Kawaguchi says that pond gardens depict the natural environment around them.

KAWAGUCHI: the whole idea of creating a garden pond to represent the sea, and then to use the earth, that’s the soil that’s dug out when you’re creating the pond to then build a mound or mounds to represent the mountains and hills, the mountain ranges behind the body of water.

VO: Some had received training in Japan; most hadn’t.

SHIMIZU: for some reason, he decided he’ll build a rock garden, and he did this for the next five years, every day. He built this rock garden.

TOM IKEDA: So more of a traditional Japanese type of rock garden?

SHIMIZU: No, he had no idea, he was not a gardener.

VO: That was Henry Shimizu. He was incarcerated at New Denver incarceration camp in Canada. Some 20,000 people of Japanese ancestry were imprisoned in Canada.

VO: So incarcerees didn’t build rock gardens just in the U.S. concentration camps. Henry Shimizu’s neighbor–and most of the gardeners in the camps—may have lacked formal training in Japan, but that did not mean that there was not skill or tradition involved. At Manzanar, many of the gardeners had spent years learning about horticulture in L.A.

KAWAGUCHI: although they may not have trained in Japan, they were extremely technically skilled landscape artists or landscapers.

ANNA TAMURA: People were really creative, adapting and using the natural materials and being expressive of the time, reflective of the time.

VO: That was Anna Tamura, who has written extensively on gardens in Japanese American concentration camps. She says one way these gardeners adapted to their camp environment was by using local rocks.

TAMURA: And at Manzanar there were two main types of rocks that were collected. There were granite, huge boulders … because the granite was native indigenous to the Sierra Nevada Mountains. And then on the other side, where the Inyo mountains, where it was metavolcanic rock, very jagged, red colored, hued rocks.

VO: In contrast, at Minidoka—

TAMURA: At Minidoka, it was mostly basalt, because that was the natural material behind the camp.

VO: Using local stones became a way to make homes for themselves in an unfamiliar place, behind barbed wire. It allowed incarcerees to forge a relationship with the landscape around them. Selecting the right rocks for a project was a crucial part of the process of creating a garden, says Kawaguchi.

KAWAGUCHI: It is quite difficult finding stones. It is not that you can just go out and get a stack of stones and then come back and you know sort of wonder what you can do with them…

VO: And that is just what the gardeners in the camps did.

SUMIKO SAKAI KOZAWA: Mr. Kato would always do everything himself, putting the rocks in place, and he’s looking at the rocks and … “This has to be faced so and so.”

HENRY NISHI: Placing rocks, it is an art.

OGAMI: …there was feeling in placing rocks.

VO: But, of course rocks aren’t exactly known for being light. Midori Suzuki’s father, Zenichi Takaha, built a rock garden at Topaz, in Utah.

MIDORI SUZUKI: Dad in the beginning, he was on some kind of a work crew. … he would bring back all those rocks … I don’t know how he managed–

SUZUKI: They had to be awfully heavy.

VO: At Minidoka, Mr. Yasusuki Kogita, a former businessman, was also undeterred by the size of the boulders he found. Here’s Tamura again:

TAMURA: when he and his two sons were sent to Minidoka he decided that he was gonna spend his time building a rock garden outside of his barrack. And so what he did was he fabricated with scrap lumber, a wheelbarrow—really large wheelbarrow—and he got his two young sons who were in elementary school…

And so over the course of many months, he and his sons would dig out these basalt boulders, dislodge them, get them into the wheelbarrow. Some of them were much larger than the wheelbarrow and bring them back to his barrack.

VO: And then there was the added difficulty that at most of the camps, the gardeners were stuck behind barbed wire.

TAMURA: they would have to get permission to leave the camp to use the government vehicles to drive out out of the camp and go into the natural areas behind the camp away from the camp. At Manzanar they went as far as 75 miles away from Manzanar to locate Joshua trees and bring Joshua trees and rocks to the camp.

VO: Why did incarcerees create these gardens? There were many reasons—boredom, the desire for a change of scenery, a tactic against dust storms in these dry, desert regions. The fact that it was one of the few things they could control in camp. But that’s not all, says Tamura.

TAMURA: There is also this sense of wanting to create beauty in a ugly place, right, a place that exhibits injustice, imprisonment, everything that was taken away, indignity and to be able to create beauty in that environment was one way that they exhibited their own power over their situation.

VO: And then, in 1945, the incarcerees had to leave their gardens behind.

TAMURA: So at Manzanar, what happened is after World War Two, the barracks were were removed, auctioned off, and the land just sat there and natural processes took over.

And so over those 70 years, the rock gardens became covered.

VO: But, they were still there, buried just beneath the surface. After the war, the federal government sold off whatever it could. But the rocks remained.

TAMURA: Now, they’re not barracks, they’re the rock gardens that didn’t have any financial value or material value. And so when people left the camps, they couldn’t bring them with them in most cases. And so they left a piece of their artwork and artistry and creativity in the camps. And so now when you go there, you can see them and have a real personal direct connection to those places, and those people through those rocks.

VO: The rocks from Mr. Kogita’s garden at Minidoka—which he and his sons had meticulously gathered with their makeshift wheelbarrow—were no longer there, though. Like Seiichi, he had brought the rocks back home with him after the war.

TAMURA: And when the WRA said, well—

VO: That’s the War Relocation Authority, the governmental agency responsible for Japanese Americans’ forced removal and imprisonment.

TAMURA: —when the WRA said, well, you know, we’re gonna pack up people’s belongings, and you can bring what you want back to, you know, your home. His dad said, Well, I want the rocks to be brought back because I collected all of these rocks at Minidoka…

VO: The rocks were still in storage when he died. But his son later used them to build a rock garden at his home in Beacon Hill.

TAMURA: Paul mentioned to me yesterday that he goes out there and sprays the rock so that the moss will continue to grow on them even during the summertime and they’re treasures for the family now.

VO: In the last ten years, some of the gardens at Manzanar and Minidoka have been excavated. The effort was led by Jeffrey Burton, an archaeologist with the National Park Service. He was assisted by volunteers.

TAMURA: Many of them were actual Japanese American survivors who had been incarcerated at Manzanar or other camps and their descendants…

VO: The rock gardens became a way of preserving the memory of the camps. This is a personal story for Tamura. In 2000, she was planning a road trip from Seattle to Salt Lake and while plotting out her route on the map, she saw a familiar name. Minidoka.

TAMURA: And I thought to myself, “hey, wasn’t that where my family was sent during the war?” And that was literally the extent of what I knew in the year 2000.

I had never heard anything about it from my Issei grandparents, from my mom who was a baby in camp, my uncle who was a teenager in camp, my two aunts, I had never heard anything about it. And I knew that they were at Minidoka. But that’s all that I had known.

I drove to the town of Minidoka because I didn’t know anything. I had no documents or anything. And I got to the town and they said, Oh, actually, the Camp Minidoka is 50 miles back West. And so then I turned around, drove 50 miles back West.

VO: A landscape architect in training, she began to do research on the gardens at Manzanar and Minidoka.

TAMURA: … it was one of those turning points in my life, where I realized, Wow, my family lived here for three years. I know nothing about this. I feel horrible that I know nothing about it.

VO: “I know nothing about this.” I can relate to that. For me, that moment was on my grandmother’s first trip back to Heart Mountain fifty-five years after she left. I was sitting in the back seat while my parents bickered over whether we had already driven by it.

For sixty years, our history was something you could drive by without even noticing. That’s changing now. There’re museums at Heart Mountain, Topaz, Minidoka, Manzanar, McGehee, Arkansas, L.A. and San Jose. Several of the sites have National Park Service designations. My grandmother tries sometimes—rarely—to talk about the camps, but I can tell how hard it is for her. She’s the only one left in my family who lived through them.

NAGATA: there’s this absence that really signals the presence of something that’s negative, and yet a sense that you cannot ask more questions about it.

VO: That was Dr. Nagata. That absence, she’s referring to? It’s still there. When my great-grandfather got off the train in Fresno, there was nowhere to take his crates of rocks. He was homeless. In the months after he got back and his family came to join him, they lived in a shed on the farm where he was working. I asked my grandmother once what happened to his rocks. She didn’t know. Her best guess? He’d left them at the train station.

[End theme.]

VO: In the following episodes, we’ll continue to explore how ordinary objects carry the memory and stories of Japanese Americans’ World War II incarceration. The incarceration wasn’t one moment in their lives–it was many small indignities that accumulated over years. And, as we hope you’ve begun to see—sometimes the things that weighed the most and that we’ve carried the longest took up no space at all.

[music]

VO: You’ve been listening to Campu. Campu is produced by Hana and Noah Maruyama. The series is brought to you by Densho. Their mission is to preserve and share the history of the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans to promote equity and justice today. Follow them on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram at @DenshoProject. Support for Campu comes from the Atsuhiko and Ina Goodwin Tateuchi Foundation. We received assistance from Natasha Varner, Brian Niiya, and Andrea Simenstad.

This episode included excerpts from more than 60 Densho oral histories and interviews conducted by Frank Abe for his film Conscience and the Constitution. The names of the incarcerees featured in this episode are: Mits Koshiyama, Roy Doi, Emi Somekawa, Jim Akutsu, Amy Iwasaki Mass, Joan Ritchie Doi, Frank Emi, Hal Keimi, Lawson Sakai, Jim Hirabayashi, Sumi Uyeda, Tom Matsuoka, Kazuko Uno Bill, Henry Shimizu, Lily Hioki, Nancy K. Araki, Tomiko Hayashida Egashira, Hatsuko Mary Higuchi, Elaine Ishikawa Hayes, Peggie Nishimura Bain, Fusako Yamamoto, Homer Yasui, George Wakiji, James Yamazaki, Frank Miyamoto, Tsuguo “Ike” Ikeda, Kara Kondo, Tom Akashi, Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, Kazuko Sakai Nakao, Richard Murakami, Frank S. Fujii, Richard Iwao Hidaka, James Omura, Gloria Kubota, Donald Tamaki, Grace Sugita Hawley, Grace Shinoda Nakamura, Grace Oshita, Minoru Tajii, Cookie Takeshita, Taketora Jim Tanaka, George Yoshinaga, Ted Nagata, Yooichi Wakamiya, Nelson Takeo Akagi, Frank Sumida, Bob Utsumi, Sally Kitano, Dave Tatsuno, Sumiko Yamauchi, Nobuko Omoto, Kitako Izumizaki, Peggy Tanemura, Flora Ninomiya, Chiyoko Yano, Mako Nakagawa, Fumiko Hayashida, Roger Shimomura, Henry Miyatake, Tosh Yasutake, George Izumi, Arthur Ogami, Frank Isamu Kikuchi, Henry Nishi, Sumiko Sakai Kozawa, and Midori Suzuki.

VO: You can find a complete transcript at densho.org/campu.

Discussion Questions

- Is there a landmark near where you live that has a name that was given to it by Indigenous people? Is that name still used? Why or why not?

- How many generations have your ancestors been in the U.S.? When and from what countries did they come? Or have your ancestors always been here?

- What does the comment, “Silence can take up a lot of space” mean to you?

- If you were suddenly forced to leave your home, and you could only take what you could carry, what would you take?

Visit the Campu Education Hub to see full discussion questions, lesson ideas, and activities.