CAMPU: Episode 2 “Paper” Transcript

Keep scrolling to read the transcript, or download a copy here.

VO: Hey, this is Noah. You may not have heard my voice before, but this isn’t our first time meeting. I’m Hana’s brother and collaborator, and Campu’s resident sound and music guy… and this episode’s narrator. If you like what we’re doing, subscribe, share, leave us a review on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you’re listening to this. It really does help us out. Thanks so much.

Even before the forced removal, the federal government was collecting a paper record on Japanese Americans. As early as 1936, the U.S. had—under FDR’s direct orders—begun to compile “a special list of those who would be the first to be placed in a concentration camp in the event of trouble.”

VO: By 1945, the WRA had a file on pretty much every single person who was incarcerated. And that was just the tip of the iceberg: the Department of Justice, U.S. Army, Immigration and Naturalization Service, and the Wartime Civil Control Administration all collected their own records.

These records include everything from correspondence between government officials, to reports on potential sites, land-lease agreements, policies for running the centers, updates, camp newspapers, signs, propaganda. And then there are the individual folders—120,000 of them—which contain health records, report cards, an individual record, correspondence with WRA officials, notes about any property they owned. It sounds like they meticulously documented and organized every detail they could collect. But actually the files are a mess.

VO: There are stains where people spilled food or coffee on the records while filling them out. They’re folded and creased and crinkled and yellowed with time. Scarred with residues of rust from paper clips and staples. It’s not unusual to find one person’s document in another person’s folder—often a family member’s, but sometimes just a stranger with a similar name. Some documents are loosely ordered by date; others are just stuck in at random.

[Begin theme.]

VO: We’re gonna take a look at this giant mess of paper. And if that doesn’t sound boring to you, well, it probably should. But bear with me. After Japanese Americans had left, after the barracks had been sold off for a dollar apiece and the guard towers dismantled and the fences shipped away, most of what remained of the American concentration camps were mounds and mounds of paper. Papers that told us about choices the incarcerees made, big and small. And that tell us little—heartbreakingly little—about their anger and uncertainty and fear and hope. About how even in camp, people were still just being people.

[Theme.]

VO: From Densho, I’m Noah Maruyama and this is Campu.

In this episode we’re talking about paper—the stories it tells, the ones it doesn’t, and what that says about power in historical narratives. I asked Hana to take me through the documents she found in our grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ folders. First up, Grandma’s folder.

NOAH: Jones personality reading scale.

HANA: It says our only basis for until our school adopted the personality rating scale shown here are only bases for reports to businessmen who were inquired about the personality traits of our former students, or grades, activities. Our activities participated in and the hazy recollections of teachers. Realizing the need for some fairly reliable form of trait rating, which might become part of the student’s permanent record, we went to work to remedy this weakness.

NOAH: Was this just for girls?

HANA: I think so. Because Kiyo and Seiyo don’t have it in theirs but Kats does.

VO: My great uncles Kiyoshi and Seiyo, and great aunt Katsuko, respectively.

NOAH: Wait, so, I see listed among ability to get along with others is attractive.

HANA: Because that that definitely plays into how, how well you get along with people is how attractive you are.

NOAH: emotional stability, a sense of humor, poise, dignity, optimism? They’re grading you on optimism while you’re in a concentration camp?

HANA: Right?

HANA: So, the personal grooming one is like the one that irks me the most because it’s like well groomed, clean, unoffensive, nice-appearing, fingernails well-manicured, neat, inconspicuous, hair well cared for and carefully and modestly dressed.

NOAH: Huh. This does sound like what every teenage girl needs is—

HANA: Yeah, definitely you wanted to know is like how this teacher is judging you.

HANA: So then we have her report cards—

HANA: Got straight A’s. But a B in phys ed. Oh, wait. Oh yeah, she also got another B in phys ed.

NOAH: Well, she got an A minus in her first semester.

HANA: So the next document is her dental records.

HANA: And I think out of respect for her, we should maybe not talk about what was on those medical records.

NOAH: Yeah.

HANA: Not that I can read them. I have no idea what they say.

HANA: You’re actually not allowed to see these records unless the person is deceased, or you have a form from that person saying that you’re allowed to and it has to be notarized too.

HANA: You can also see like what assembly center she went to, which is kind of cool and where she lived at the assembly center because, like, grandma’s forgotten most of that stuff, I think, or she won’t talk about it.

NOAH: Yeah.

HANA: It could be either.

NOAH: They note the race as white, Japanese or other.

HANA: Why on earth is Japanese not first? Most of the people who would have been filling out this form are Japanese, obviously, because no one outside of a concentration camp was being asked to fill out this form.

NOAH: Okay, let’s move on.

HANA: Yeah, so, this is the application for leave clearance—and it’s for Chiyo Maruyama, which is our great-grandmother on grandpa Yosh’s side.

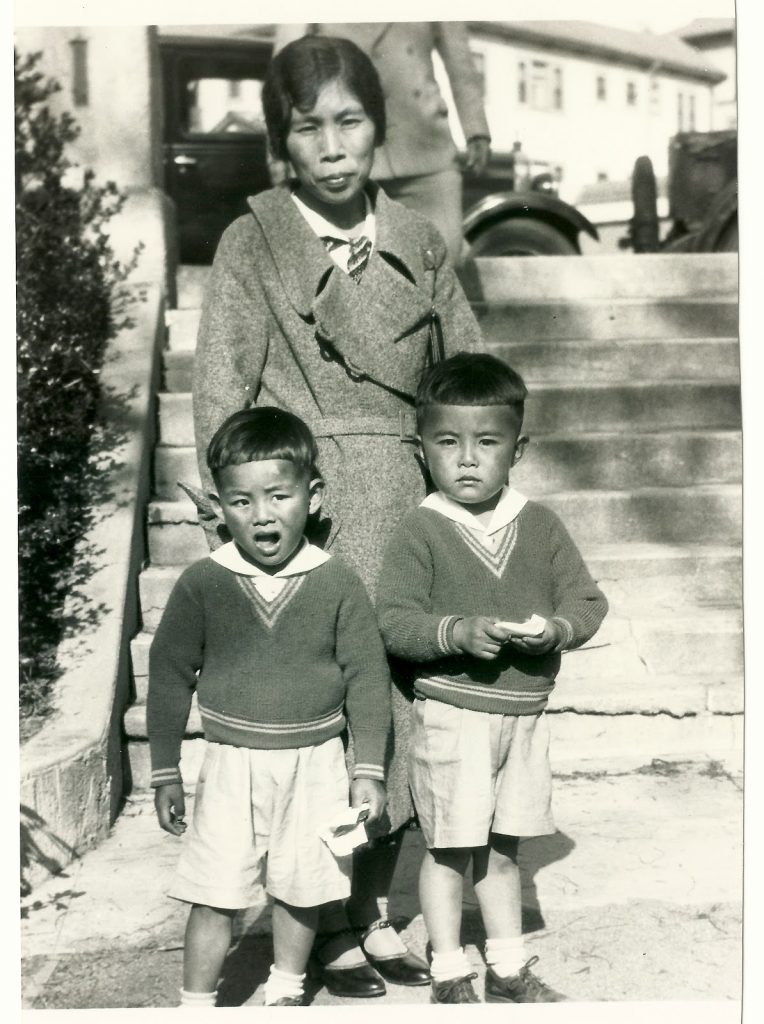

VO: We never met our great-grandmother. My grandfather died when I was a baby. I never got to hear much about his side of the family. This folder is my first time meeting her.

HANA: And it’s got like all of this information about her, you know, when she was born—1895 in Nagano, Japan. Oh here’s all this information about her parents, which would be our great great grandparents. She is not a registered voter, which she couldn’t be because she wasn’t a citizen. She was four-eleven. Man, she was short. I say that as someone who’s five foot three.

VO: This document Hana’s describing may sound pretty harmless. Good, even. An application for leave clearance. Isn’t that what everyone wanted? But this little form changed 120,000 lives. It’s more commonly known as “the loyalty questionnaire.” Here’s Dr. Roger Daniels, a historian on the incarceration:

ROGER DANIELS: Apart from the initial stupidity … of putting Japanese Americans en masse in camps and leaving alone the whole moral thing, perhaps the most stupid … thing was this questionnaire for leave clearance. The motives were not really bad. The WRA, it was a bureaucratic organization, they said, “Well, let’s, we can let loyal Japanese Americans go out,” so they hand out this goddamn questionnaire, as if that were a way to do it.

VO: The way the WRA intended to gauge Japanese American “loyalty” was by asking all adults in the camps two questions. Dr. Frank Miyamoto, an early Nisei sociologist, did research on the incarceration while he was confined at Tule Lake. He said,

FRANK MIYAMOTO: …there was a lot of ambiguity to these questions. In fact, more than ambiguity, it was they were very poorly phrased questions.

TOMMY T. KUSHI: You read it, and you don’t know what it says. “Do I vote ‘yes-yes,’ ‘no-no’?” The wording on it is weird.

VO: Question 27 asked if incarcerees were willing to serve in the armed forces.

YUKIO KAWARATANI: —which people said, “That’s like asking to be drafted.”

VO: Never mind if you were over draft age, an immigrant, or a woman—the question was the same for everyone. It also wasn’t clear what it meant: If you said yes, were you volunteering?

MITS KOSHIYAMA: On question 27, I qualified my answer by saying, “Yes, I would be willing to serve in the United States Army but I would only do so if my constitutional rights were returned to me first and … I was a free citizen again.”

VO: And then there was question 28.

MIYAMOTO: “Do you forswear allegiance to the Emperor of Japan,” and so on.

VO: There were rumors going around that question 28 was a trick—that if you answered yes, you were confessing to having had allegiance to the emperor.

MIYAMOTO: Well, if you had never felt any allegiance to the Emperor, why should you forswear [Laughs] your allegiance?

GEORGE KATAGIRI: The young Niseis were saying … it’s a trick question, you know. Don’t answer it. And so there was this confusion over this dumb questionnaire that tried to determine loyalty.

TSUGUO “IKE” IKEDA: if I’d said, “Yes” to that, then that would mean I had that allegiance.

VO: Even if you didn’t believe the rumors, the question was insulting to Nisei, who had been born and—for the most part—raised in this country.

GEORGE KATAGIRI: I never had allegiance to the emperor.

VO: For their part, the Issei worried what would happen to them if they agreed to that—remember, they weren’t allowed to become U.S. citizens at that point.

CHIZUKO NORTON: —we were given this loyalty oath—

SUE KUNITOMI EMBREY: It caused a lot of confusion among the Issei—

GEORGE KATAGIRI: dad was saying, “My gosh, I can’t be a citizen of the United States. If I disavow allegiance to the emperor, I’d have no country.”

SHOSUKE SASAKI: —become a man without a country.

NORTON: —without a country—

EMBREY: —without a country—

NORTON: —even if that other country did do this horrible war act on the United States.

EMBREY: —they would lose their Japanese citizenship if they did that—

NORTON: my parents decided that they would not sign. … “You allow us to become U.S. citizens and then we will.”

VO: Reasonable concerns, right? Wrong. The only acceptable answer to these questions was an unqualified “yes.” Answering no, refusing to answer, or even just qualifying their “yes” with a comment were all classified as “disloyal.” For some, the answers were easy.

EDDIE OWADA: For me, I was American, I wanted the American way. I didn’t even want Japanese.

TOM AKASHI: And he says, “I came to America, I adopted America. America is my home. It is your home, and I will do whatever possible to defend my home and my family.”

OWADA: So to me, “yes-yes” was easy.

GEORGE YOSHIDA: I said “yes-yes”—

SEICHI HAYASHIDA: I answered “yes-yes,” my wife answered “yes-yes”—

GEORGE YOSHIDA: —without any doubts, without much debate in my mind.

SEICHI HAYASHIDA: —with no question, period.

MARIAN ASAO KUROSU: it was a yes. That’s why we said “yes-yes”.

KAZIE GOOD: There was no problem with me, I registered, I was a “yes-yes” from the beginning. But…

VO: But in a lot of cases, it was a complicated decision—even if the answer was yes-yes.

BILL HOSOKAWA: I was very leery about the way the questions were phrased … I don’t want to go to war right now, with my wife pregnant and a little baby…

ARCHIE MIYATAKE: I’d rather live here and be loyal to United States, … but I will not shoot people.

VO: Some people were just pissed off.

GENE AKUTSU: You sent me to Puyallup, you sent me to Idaho. And I’m through going wherever you’re going to tell me to go. So I answered no to that.

FRANK KITAMOTO: my dad had just been released from Missoula, and that questionnaire came around. … and he was so angry that he just refused to sign “yes-yes.”

MINORU KIYOTA: I was interviewed by the FBI because I was a Kibei.

VO: The term Kibei refers to Nisei educated in Japan.

KIYOTA: he called me a Jap and all that dirty stuff, and then told me … I cannot leave the camp. … And because of that shocking event, … I said, “No-no.”

CEDRICK M. SHIMO: So I was pretty angry by then … If it weren’t for that, I probably would have answered “yes-yes.”

VO: It didn’t always feel like much of a choice.

TETSUSHI MARVIN URATSU: I said, Joe, you know if a guy had a gun at my forehead and told me what to do, I’ll do whatever he tells me because I want to live another day.

MIYAMOTO: for most of us, I guess the feeling was … “It’s not a fair question directed to us, but what can we do? We want to get out of these centers.

GEORGE ISERI: the government can say, “Okay. We’ll put you into solitary confinement or whatever.” … I’ll be a hypocrite. I’m gonna get the hell out of here.”

VO: Some refused to answer the questions altogether.

FRANK EMI: “Under the present conditions and circumstances I am unable to answer these questions.”

TOKIO YAMANE: I told them that I had no intention of answering the questions.

VO: Even though the questionnaire was framed as a matter of loyalty, it had serious implications for families. No one really knew what was going to happen to the no-nos, especially at the beginning. Would they be repatriated? Would the family be separated? Would you see each other again?

AKIO HOSHINO: to me, there wasn’t much choice.

FRANK KITAMOTO: you know, the rumors are going around that if you don’t sign “yes” you’re gonna be taken away and sent to Tule Lake or back to Japan in exchange for Americans trapped in Japan.

BETTY MORITA SHIBAYAMA: …my father said that he had to answer according to his children, ’cause he wanted to remain with the children.

TED HAMACHI: …my dad wanted to go to Tule Lake. And then I just objected—

EIKO YAMAICHI: I said, “I’m gonna say ‘yes-yes’ because I want to go to school outside.” … Then that’s when my father said, “No, you can’t go.”

HITOSHI NAITO: …if you say “yes-yes,” you’ll probably be separated from your family—

EIKO YAMAICHI: “and then you get to go and I say ‘no,’ then the family will be split.”

HITOSHI NAITO: family was the only thing I had left.

AKIO HOSHINO: the only sure thing that I had at that time. … and so I decided that I’ll stick with the family unit…

TED HAMACHI: I told my dad that, “You guys can go—”

EIKO YAMAICHI: So I said, “I’m still going to go ‘yes-yes,’—

TED HAMACHI: I’ll be okay. I’ll just move into the bachelor’s quarters—

EIKO YAMAICHI: that’s the way it’s going to be.”

TED HAMACHI: —just leave some towels and a little bit of money and I can get by.”

EIKO YAMAICHI: So he reluctantly also said “yes-yes.”

AKIO HOSHINO: … my parents … being they’re non-citizens here, I guess it was sort of understood that they would sign “no-no.” … so I decided I would go along with them.

MARIANNE WEST: my father was “yes-yes”—

NORTON: My answer was yes—

HANAKO HOSHIYAMA FUKUMOTO: I said “yes-yes.”

MARIANNE WEST: but I couldn’t see that.

NORTON: —But I wasn’t able to say yes-yes.

HANAKO HOSHIYAMA FUKUMOTO: but then my husband said, “yes-no—”

WEST: I knew I was a citizen but I felt I didn’t have my rights.

FUKUMOTO: —so then they wouldn’t release him.

FRANK KITAMOTO: My mom said, she pleaded with him and said, “Sign ‘yes.’ What would the family do if you had to go to Japan?” … And she said, “I’d rather hang myself than go to Japan.” And my dad got so angry he said, “Go get a rope. Go ahead.” But he did finally sign “yes” to the two questions.

NORTON: And in the end, the family won out. And I really think that they would have won out anyway regardless.

[Break]

VO: If you didn’t answer the loyalty questionnaire yes-yes, that answer might lead to a whole new set of papers in your folder. Iku Kiriyama found a transcript of an interview with her mother about her answer to question 28.

KIRIYAMA: I have the transcript of the interview … You can see how she’s just completely frightened, intimidated, and the questions kept pounding at her. They repeated it several times in different ways to have her say, “Yes, I’m loyal.”

During that interview, “Oh, I’ll be a nurse, I’ll do anything.” … She told the interrogator that she answered “no” because … she thought that if she answered “yes,” because she’s a citizen and my father wasn’t … that he would be sent back to Japan and she would have to stay here.

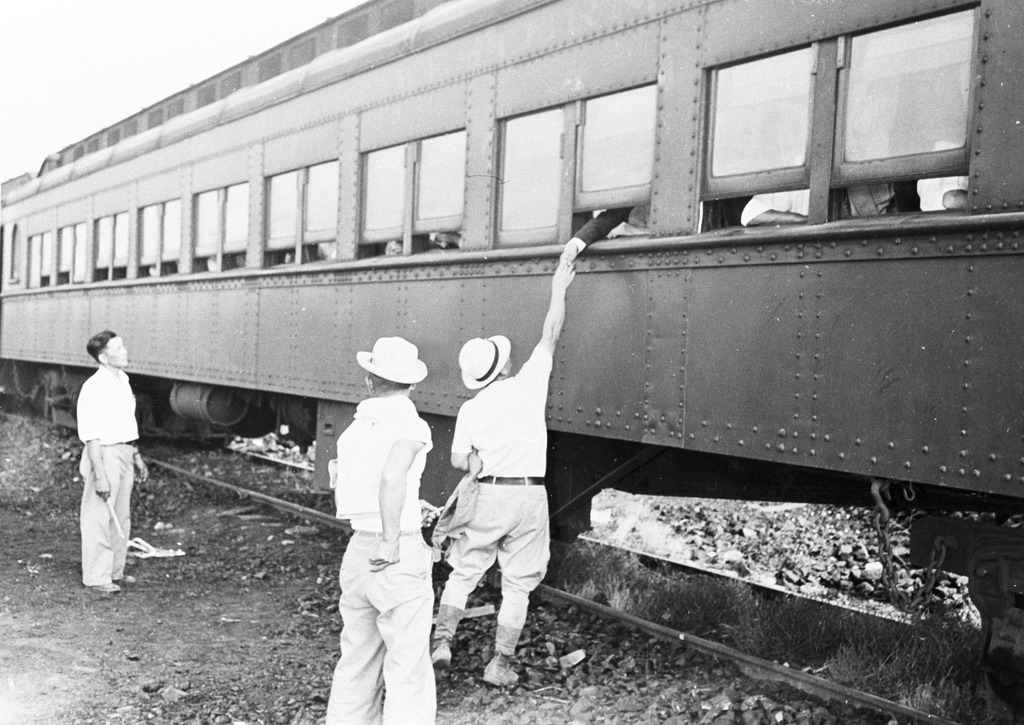

VO: At Tule Lake, the administration pressured the incarcerees to answer the questions quickly without giving them a chance to discuss them with their families. Those who refused were threatened with $10,000 in fines, twenty years in prison, or both. Jim Tanimoto was one of about 30 incarcerees from block 42 at Tule Lake that refused to complete the loyalty questionnaire.

JIM M. TANIMOTO: they dropped these forms off at the block office. And the residents of that block were supposed to go over there and pick up the forms and sign it “yes” or “no” … There were some people in our block that did sign, but there was a lot of people in our block that wouldn’t sign. They wouldn’t sign “yes” or “no,” just refused to sign, period.

VO: The Tule Lake administration sent dozens of protesters to nearby county jails in response.

TANIMOTO: Our block, like I said, most of ’em didn’t sign, and they wanted to make an example out of our block so other blocks wouldn’t do what we did.

TANIMOTO: …one evening, after dinner, our block was surrounded by military police. They had rifles with bayonets on them, and they surrounded our whole block.

TANIMOTO: then we came out, the soldiers made us count off.

TANIMOTO: And they says, “Okay, you guys get in the truck,” we got in the truck. We didn’t know where we was going.

TANIMOTO: we were sorted out and carted away to county jail.

VO: Since there were no criminal charges, the county jails couldn’t continue to hold them, and they were eventually removed to an isolation center fenced off from the rest of the camp—for months.

TANIMOTO: We weren’t charged with anything, so there was nobody there that could explain to us why we’re here, other than the fact we knew that our group didn’t sign these particular papers.

VO: The WRA eventually changed the language on the loyalty questionnaire and started allowing qualified answers to some degree.

GEORGE MATSUMOTO: they changed their questionnaire to, “will you abide by the laws,” or something. If they had asked me the same thing, I would’ve said yes.

SASAKI: I made no secret of the fact that I was going to say no, be one of the no-no boys. … I didn’t have to. Because the day before I was supposed to go up for that kind of questioning, they changed the rules. They dropped that stupid question. If they hadn’t done that, who knows maybe I would have gone to Japan.

VO: But the change in language didn’t always clarify things.

AKASHI: the Isseis were given this form that the females got—and it said, “Would you serve in the… nursing corps, or the women’s army auxiliary corps,”

AKASHI: He says, thought that was nonsense, so he left it blank.

VO: And the damage was already done.

AKASHI: Tule Lake was just, it was chaos.

KENGE KOBAYASHI: There were fights going on and people getting beat up.

ISERI: And the people were getting beat over the head and things in the camp—

AKASHI: fights, arguments, brother against brothers, against friends.

ELAINE ISHIKAWA HAYES: people were getting hurt, or beaten.

AKASHI: Just fistfights … And a lot of name-calling, inu in particular.

VO: Inu means dog in Japanese. It was an insult for people rumored to be government informants.

ISERI: And at that time, the antis were after us guys and called us dogs.

HAYES: they were being called inu and being harassed—

HANK SHOZO UMEMOTO: Inu is one of the lowest things you could think of that you could be called—

HOSHINO: it did raise quite a stink in the camps. It broke apart families, and you can’t blame ’em.

VO: It could also really impact someone’s sense of self during an already difficult time.

GEORGE KIYO WAKATSUKI: I think his experience from when he was in Bismarck… there was a story going around that because Dad could read Japanese and speak English, he was interpreting this American newspaper to the Japanese prisoners that were there with him. And … the prisoners I guess were saying that he wasn’t telling them the truth … so they called him inu … so he’s like a traitor. … I think when he came back in camp, that was following him. … And after that he just drank.

VO: The whole reason the federal government had begun collecting the loyalty questionnaires in the first place was because they wanted to recruit Nisei volunteers. Here’s Michi Nishiura Weglyn, who was incarcerated at Gila River as a teenager and later wrote the seminal book Years of Infamy.

MICHI WEGLYN: And the WRA decided, “Well, we’d like to be able to expedite the release of those who we feel are loyal so that they could help in the war effort, in industry, or on the farm, on the railroads, etcetera.”

ROGER DANIELS: they didn’t bother to make up their own questionnaire … they simply adapted a questionnaire that the military was already using to segregate draft age Japanese Americans who had volunteered.

VO: Not many in the camps were particularly eager to enlist. This probably shouldn’t have come as a surprise, but to the army it did. Here’s Dr. Arthur Hansen, a historian of the incarceration:

ART HANSEN: they expected to get 3,000 volunteers out of the camps and they ended up getting 800.

VO: The army got considerably more volunteers from Hawai‘i, where there was no mass removal and incarceration.

CLIFFORD UYEDA: for the very first call for volunteers from the camp, only 800 and something went in. Now take that with Hawaii where over 10,000 volunteered, and one can see that there was this resentment within the camp.

[break]

VO: Some did volunteer from the camps though.

TOSH YASUTAKE: I decided that maybe if I did volunteer that it might help my dad get released a little earlier. So I did volunteer. … and then I didn’t have nerve enough to tell my mother so I asked a good friend of ours who was the Episcopal minister in the camp … if he would go and tell my mother for me. [Laughs] I didn’t have the guts to tell her myself.

VO: But most took a stance similar to Art Ishida’s:

ART ISHIDA: No, I’m not volunteer unless I’m treated as U.S. citizen, and … I think I’m still citizen so if I get drafted, yes, I’ll go.

VO: In January 1944, the army did also start drafting people from the camps. We’ll talk about that more next episode. The 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the segregated Japanese American units, won seven Distinguished Unit Citations, 21 Medals of Honor, 4,000 Purple Hearts, 588 Silver Stars and more than 4,000 Bronze Stars. Some assisted in the release of prisoners in the liberation of subcamps of Dachau.

SUSUMU ITO: We were separated from the 442nd, it was just the 522nd, we were just giving additional fire power.

MINORU ‘MIN’ TSUBOTA: and we, the 522, went up into Germany and … that’s when we just didn’t know it but we ran into the Dachau concentration camp.

ITO: And at the time of passing west of the Dachau, we were some oh, ten, fifteen kilometers to the west … we saw a lot of prisoners released, we saw a lot of dead Dachau prisoners with the stripes, dead along the road.

FRED MATSUMURA: In France, well, that’s when we went to rescue the “Lost Battalion” there.

VO: On October 27 1944, the 100th and the 442nd were ordered to rescue a battalion of men that had been trapped behind enemy lines with limited food, water, and medical supplies.

MATSUMURA: And the fighting was really fierce. We were fighting, in the forest … And they’re throwing shells at us; every time the shell hit the tree, it burst like geysers. … the machine guns emplacement by the Germans were all set up. They were so well entrenched, we had a hell of a time getting through.

VO: Of the 275, they saved 211. They suffered 800 casualties in the five days it took. Even so, they were ordered to keep pushing on and on and on. And on the 12th of November, less than 30% of them were able to stand in formation when the General who had given them their orders decided to hold them an award ceremony. When he saw K company’s eighteen remaining men, he wanted to know why the rest weren’t standing for him too.

It’s a core value of the American military, a trope even, not to leave troops behind. Still, you have to ask. Would the army have sent so many white troops to their deaths for the Lost Battalion? If their positions had been reversed, how many white men would they have given to save the Nisei soldiers?

VO: Many more served in the Military Intelligence Service—or MIS.

PAUL BANNAI: …even with my very poor Japanese—because I was not real good—I was able to, by myself, go out and try to help the troops that I was with. … So all during the war in the Pacific whenever we got prisoners of war and talked to the Japanese, we got information that was helpful down the line, saved our troop lives, made it easier for us to advance.

VO: 14 Japanese American translators served with Merrill’s Marauders, who fought behind Japanese lines in north Burma to carve a land route to get supplies to China. The unit received a Presidential Unit Citation in July 1944. General Merill later said, “As for the value of the Nisei group, I couldn’t have gotten along without them.”

ROY H. MATSUMOTO: But our mission was … to make a route to join the Burma Road … that has been occupied by Japanese when the British were chased out of there. … In order to do that, we have to chase the Japanese out of there.

VO: Here’s what President Truman said to the 442nd after they returned home:

TRUMAN: You fought not only the enemy but you fought prejudice—and you have won. Keep up that fight.

VO: In 1944, the federal government began to draft Japanese Americans from behind barbed wire, and we’ll talk about that more in our next episode. These arguments—on the loyalty questionnaire, military service—they divided the Japanese American community for decades to come. In 2019, the Japanese American Citizens League formally apologized to the Tule Lake no-nos. It was a very controversial decision.

[break]

VO: And all this started because of some paper. Two words—yes or no—could define where incarcerees were sent during and after the war, when they were permitted to leave camp, whether they stayed in the U.S. or went to Japan, and their relationship with the Japanese American community. But for something that tells us a lot about the trajectories of their lives, the loyalty questionnaire actually says very little about how they made those decisions. Hana and I pored over our great-grandmother’s questionnaire searching for insight into what may have been going through her mind when she was answering those questions.

NOAH: So hang on, I’m seeing in the names and ages of dependents who proposed to take with you. No desire to leave.

HANA: Huh. When was she filling this out? … oh, yeah, it’s March 9 1943. So it’s actually like, probably only like six months or so—maybe like nine months—after they first arrived at Gila River. … And it’s like, you know, they’ve been told all these horror stories about how they’re going to be treated once they got out of camp. And honestly, they weren’t really horror stories. They were absolutely true. Like, people would have their tires slashed and pins put out on their driveway and their houses and garages graffitied and all of this stuff when they got back. And they weren’t even allowed to return to the west coast at this point, right. So if they—if they left, they’d have to go somewhere else and make a new business somewhere outside of outside of California. And so for a lot of the Issei, it was kind of like, why would you want to leave? Where would you go?

HANA: Okay, so then we get to question 25, which is, to the best of your knowledge? Was your birth ever registered with any Japanese governmental agency for the purpose of establishing a claim to Japanese citizenship? And she says yes, because she was born in Japan. So obviously, she is a Japanese citizen.

NOAH: That’s a very confusing way to word that.

HANA: the thing about these loyalty questionnaires is they tried to make this form that was going to work for everyone. And they seemed to not recognize that people would be coming from like, very different positions.

HANA: If so registered, have you applied for cancellation of such registration? Which she says no. Which makes perfect sense because she wasn’t allowed to become an American citizen at that point.

HANA: so these two questions are the ones that cause a lot of trouble for people is 27, 28. And they’re just kind of like folded in there. Like, you would never notice them. They’d look completely innocuous on this form, but they completely change everyone’s lives.

HANA: But she does write in like very big, also non cursive letters, which is interesting to me because the rest of her form is in cursive. But she writes yes in like very big print letters. And that’s all that’s all she writes. Because that’s all she was supposed to write. She wasn’t allowed to write anything else and it’s like that says so much and so little at the same time—that yes.

VO: That’s true of much of what you’ll find in the National Archives.

CAITLIN OIYE COON: there’s a lot of data in the National Archives, but most of it was created by the government for the government. And so you can get a lot of facts. And really good historians or data driven people can pull a lot of information from those facts, right, but it doesn’t give you the personal side of what was going on in the camps.

VO: That’s Caitlin Oiye Coon, Densho archivist.

OIYE COON: And you can really only get that from … people’s personal letters, their diaries, the art that they did.

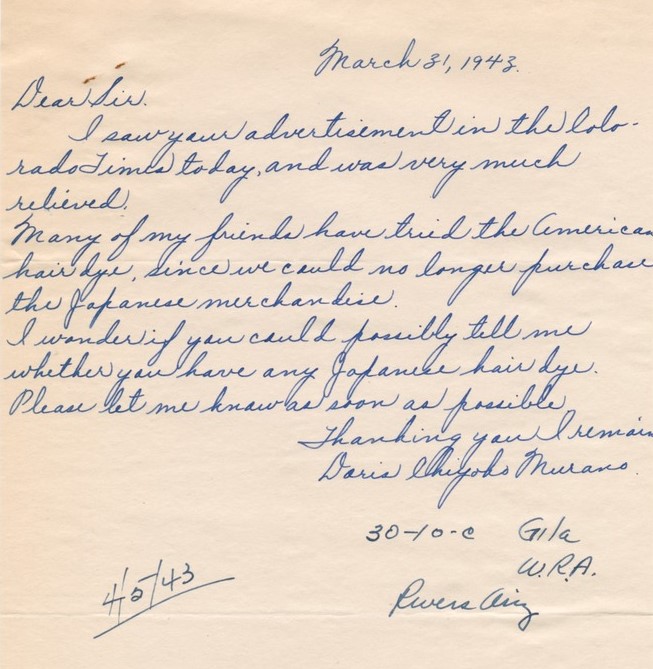

VO: Some incarcerees kept diaries. But most didn’t. And even if they did, a fair amount of that would be in Japanese—a language that the Nisei often resisted teaching their children. Still, we all have a paper trail—it’s just most paper doesn’t ever make it into the historical record. Like post-it notes. Receipts. They get lost or thrown in the trash or—if you’re like me—the carefully ordered filing system that is the back of your car. They record your late night excursion to your local CVS for that urgently needed pint of ice cream or box of Oreos, some shaving cream or soap or a six pack of beer. Our receipts are generally not things any of us would want historians of the future to examine and analyze—much less discuss in a podcast. But these too can be an important part of the historical record. Densho has digitized receipts, invoices, and letters from T.K. Pharmacy, a Japanese-owned pharmacy in Denver.

OIYE COON: I was contacted by the person who was doing the renovation on a building in Denver, I believe it was … and they took down a wall which you hear happens, and inside there was just boxes that somebody had put into the walls for some reason and then shoved into it were lots of like receipts and stuff.

OIYE COON: But then the most interesting part was there was letters … from the 1940s from people who were either living outside of the exclusion zone and requesting to make purchases from TK pharmacy, or they were from people who were actually in the camps who were trying to get different, honestly mostly sake but they were trying to buy things that they couldn’t get in camps from TK pharmacy.

VO: I volunteered at the Library of Congress one summer when I was a teenager. Yes, I was a very cool kid. Why do you ask? A very patient librarian and I carried boxes of their collections around a warehouse that was kept so cold we had to wear winter coats in the middle of the sweltering Maryland summer. They were stored in folders made from acid-free paper; we had to wear disposable gloves anytime we touched anything inside. The TK Pharmacy papers were shoved into a wall at some point, sealed off, and forgotten about.

OIYE COON: we hear about the big things that are going on, but life goes on regardless, right, and what was that life like? So, to me, that’s what’s important.

VO: The fact that this collection ended up being preserved is kind of a fluke. These pieces of paper—pieces of history—got plastered behind a wall, left to decay.

OIYE COON: Dust would be a huge problem. If there was like water leakage, then you could have mold or just the deterioration of the paper in general. And honestly, I would be worried about pests getting in and out, you know, rats or mites or any sort of bug. So must have been pretty well sealed because I did not see any.

VO: And if it didn’t get destroyed by dust or mold or bugs, there was always the possibility of plain old human disinterest.

OIYE COON: It’s a good thing that the person who opened up the wall was actually appreciative of history, rather than maybe just some random contractor who was like, Oh, I’m gonna throw out this old paper.

VO: It may not seem important, but these letters—asking for things like hair dye, mugwort, notepads, sinus meds, gum—tell us about how the incarcerees survived under these conditions.

OIYE COON: there’s a lot of stuff that we’re not going to remember, but that they were important at the time, and they tell us a lot about what our lives were like.

VO: Cod liver oil. Tea. Antacid tablets. Tooth powder. Sumi ink. Bath salts. And, as Coon mentioned, sake. Kokusui Sake. Hakutsuru sake.

HIROSHI KASHIWAGI: I remember this friend of ours coming over. … But after curfew, you know, he’s not supposed to be walking around. Well, he got caught by the MP … And so the MP drove up and knock, knock, knock… and we were frightened, of course, after curfew. And, and then he says, “You know this guy?” And I remember saying, “No, we don’t know him.” [Laughs] … But I think he was drunk anyway.

VO: Scotch, too. Whisky. Hamm’s beer. Sherry. Brandy. Soy sauce. Incense. Eyeshadow.

MADELON ARAI YAMAMOTO: Got to wear lipstick, and so it was a time to appear a little bit more grown up.

VO: A dictionary. Film. Cold meds. Japanese candy. Face lotion. Playing cards.

ISERI: We got together in the evenings and we’d play poker. The lights would go out once in a while. Well, we pass the flashlight around to play poker.

VO: An inhaler. Books. Allergy meds.

WILLIE K. ITO: you virtually slept on straws. And God help if you had any kind of allergies.

IRENE YAMAUCHI TATSUTA: we had mattresses full of hay, and I think the three of us were allergic to that, the women were. [Laughs] My mom and I had hay fever, and my sister had asthma.

MARGIE Y. WONG: And my mother used to put toilet paper inside her nose. I often wondered why. But now I know why. She had an allergy and they didn’t have antihistamines back there. And her nose would constantly run.

MIDORI SUZUKI: And our sister Tsuki, she came down with an allergy attack. So I don’t know what she ended up sleeping on, but she couldn’t sleep on that hay, because boy, did she get a bad hay fever attack. [Laughs]

VO: Okay. But is all this really part of history?

OIYE COON: history is often told from a pretty high vantage point, right? And what does that really tell you, though, about the lives of the people who are just kind of living during those times, dealing with these larger events that were happening that were outside of their control, and just still having to live their lives?

VO: Japanese medicine. A cigar. Baby bottles. A Lanteen Cap Diaphragm.

AIKO HERZIG-YOSHINAGA: I had never had any sexual experience before I went to camp, and so making love on a straw hay mattress was noisy. I mean, every time you moved a toe, crackle, crackle, crackle, you know… It was very difficult to have a honeymoon in that condition.

VO: What would it have been like to lose your virginity in a room you shared with your whole family, in a barrack you shared with strangers?

OIYE COON: To me, it just shows agency on the part of women in the camps to say … I still want to be able to control how many children I have in this environment and when I have them. … whereas so much of everything else was not in their control anymore.

VO: Japanese American women especially can come across in the archives as passive bystanders left to deal with the aftermath of the business of men. Their husbands’ arrests, their husbands’ decisions about how to answer the loyalty questionnaire and where to go after they left camp, … their sons’ military service, draft resistance.

OIYE COON: you know, so often we just don’t hear about what happens to women—

VO: But these letters refute the notion that Japanese American women were standing by as the federal government uprooted their lives.

OIYE COON: So you really hear from the people who are in there when you get these letters.

VO: Women weren’t the only ones asking for contraception. Someone asked for something called a rubber sock. Whatever that is. There was also a request for Trojans. Yes, Trojans were already around back in the 1940s. Thomas Shigekuni came across a man cleaning out the sewer outlets at Granada.

THOMAS SHIGEKUNI: I said, “What are you doing?” He says, “Keeping these condoms out of there ’cause it’s plugging up the outlet.” … He said, “I don’t know where they’re gettin’ ’em, but they’re sure gettin’ a lot of condoms.”

THOMAS SHIGEKUNI: That’s the kind of thing you won’t hear in the history books.

VO: The kind of thing that seems harmless to leave out. Maybe even embarrassing to include. But these are the details that remind us that the incarcerees were humans just like us. Weighing their options just like us. Getting angry, being rash. Having desires. And doing their best. Making decisions—small and large. Moment by moment. No more idea what came next than we have about tomorrow. Questioning themselves, changing their minds. Growing up or growing old. And going on with their lives. It’s kind of sad, isn’t it? These details are where the incarcerees’ humanity shines through the historical record. And they’re the ones that get written out of history. Or at least one version of history. But it’s not the only one out there. All because someone stored some paper behind a wall.

VO: You’ve been listening to Campu. We’re a new podcast and we don’t pay to advertise, so please subscribe, like, share, and/or leave us a review on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you’re tuning in. Or hey, just tell someone else if you think they’d like it! Visit densho.org/campu for additional resources and this episode’s transcript.

VO: Campu is produced by Hana and Noah Maruyama. The series is brought to you by Densho. Their mission is to preserve and share the history of the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans to promote equity and justice today. Follow them on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram at @DenshoProject. Support for Campu comes from the Atsuhiko and Ina Goodwin Tateuchi Foundation. We received assistance from Caitlin Oiye Coon, Natasha Varner, Brian Niiya, Naoko Tanabe, and Andrea Simenstad. The Truman quote came from Universal Newsreels, Harry S. Truman Library. This episode included excerpts from more than 60 Densho oral histories and interviews conducted by Frank Abe for his film Conscience and the Constitution. The names of the narrators featured in this episode are: Roger Daniels, Frank Miyamoto, Tommy T. Kushi, Yukio Kawaratani, Mits Koshiyama, George Katagiri, Tsuguo “Ike” Ikeda, Chizuko Norton, Sue Kunitomi Embrey, Shosuke Sasaki, Eddie Owada, Tom Akashi, George Yoshida, Seichi Hayashida, Marian Asao Kurosu, Kazie Good, Archie Miyatake, Art Ishida, Art Okuno, Gene Akutsu, Takeshi Minato, Minoru Kiyota, Bill Hosokawa, Tetsushi Marvin Uratsu, George Iseri, Cedrick M. Shimo, Frank Emi, Tokio Yamane, Betty Morita Shibayama, Hitoshi “Hank” Naito, Ted Hamachi, Eiko Yamaichi, Akio Hoshino, Hanako Hoshiyama Fukumoto, Marianne West, Frank Kitamoto, Iku Kiriyama, Jim M. Tanimoto, George Matsumoto, Kenge Kobayashi, Elaine Ishikawa Hayes, Hank Shozo Umemoto, George Kiyo Wakatsuki, Michi Weglyn, Arthur Hansen, Clifford Uyeda, Tosh Yasutake, Fred Matsumura, Minoru ‘Min’ Tsubota, Susumu Ito, Paul Bannai, Ray H. Matsumoto, Hiroshi Kashiwagi, Madelon Arai Yamamoto, Willie K. Ito, Irene Yamauchi Tatsuta, Margie Y. Wong, Midori Suzuki, Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, Thomas Shigekuni. Thanks for listening.

Discussion Questions

- What kind of “paper trail” do you have? What papers document your life? (Prompts: medical records, school records, birth certificate, etc)

- Imagine that all of your purchases from a drugstore were saved for posterity. What would these receipts say about you?

Visit the Campu Education Hub to see full discussion questions, lesson ideas, and activities.