Densho’s new podcast, Campu, tells the story of Japanese American incarceration like you’ve never heard it before. Brother-sister duo Hana and Noah Maruyama weave together the voices of survivors to spin narratives out of the seemingly mundane things that gave shape to the incarceration experience: rocks, fences, food, paper. Follow along is they move far beyond the standard Japanese American incarceration 101 and into more intimate and lesser-known corners of this history.

On this page, you’ll find educational material designed for self-guided learning or to prompt discussion, geared towards high school and college-age learners. The discussion questions and lesson ideas are centered around each episode and meet curriculum goals correlated to standards in several subjects.

Contact education@densho.org if you have any questions.

Episode 1: Rocks

This episode is about the forced removal of Japanese Americans in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, but it’s also about the bedrock that lies beneath. Literally. We talk about rocks — not just in the geographic sense, but also the stories they hold: of origins and stolen lands; of passing time and reviving tradition; of memory and of the questions we learned not to ask.

See the full transcript here.

Discussion Questions:

- Is there a landmark near where you live that has a name that was given to it by Indigenous people? Is that name still used? Why or why not?

- How many generations have your ancestors been in the U.S.? When and from what countries did they come? Or have your ancestors always been here?

- What does the comment, “Silence can take up a lot of space” mean to you?

- If you were suddenly forced to leave your home, and you could only take what you could carry, what would you take?

Lesson Idea:

Try writing a haiku about something that you have collected. Before starting your haiku, reflect on the following questions: What did you collect? Why did you collect that item? How did your collection start? For info on haiku (description, history, format): Haiku

Episode 2: Paper

After Japanese Americans were released from incarceration, most of what remained were mounds and mounds of paper. Papers that told us about choices the incarcerees made, big and small. About how even in camp, people were still just being people. In this episode we’re talking about paper—the stories it tells, the ones it doesn’t, and what that says about power in historical narratives. See the full transcript here.

Discussion Questions:

- What kind of “paper trail” do you have? What papers document your life? (Prompts: medical records, school records, birth certificate, etc)

- Imagine that all of your purchases from a drugstore were saved for posterity. What would these receipts say about you?

Lesson Idea:

Search the Densho Digital Repository for one of the names in the PDF and see what you can find out about them by looking at their paper trail.

[Note: Some students may not be able to read cursive. Point out that handwriting styles have changed over time, making it challenging to read old documents.]

For tips on how to search the Densho archives, please see Navigating the Densho Digital Repository. Start by typing the name of the person in the “Search” box.

When you have completed your search, write a paragraph about the person, including:

- What kinds of documents did you find?

- What kind of documents or other evidence of the person were missing?

- What questions do you still have that weren’t answered by the paper trail?

Episode 3: Fences

Not all fences are of the white picket sort. Many, in fact, represent a reality that goes against everything America imagines itself to be. In this episode, we’re going to talk about the barbed-wire fence of World War II concentration camps—what it meant to the people it imprisoned, and to those it kept out. See the full transcript here.

Discussion Questions:

- Consider the sayings, “The nail that sticks up gets hammered down” and “The squeaky wheel gets the grease.” What do you think each of these sayings mean? Which saying do you identify with? What is an example of each of these from the episode?

- To some, fences represent confinement and to others they represent safety. The American flag is another common symbol that has very different meanings for different people. Name two different things it represents to different groups, and then think about what it means to you.

Lesson Idea:

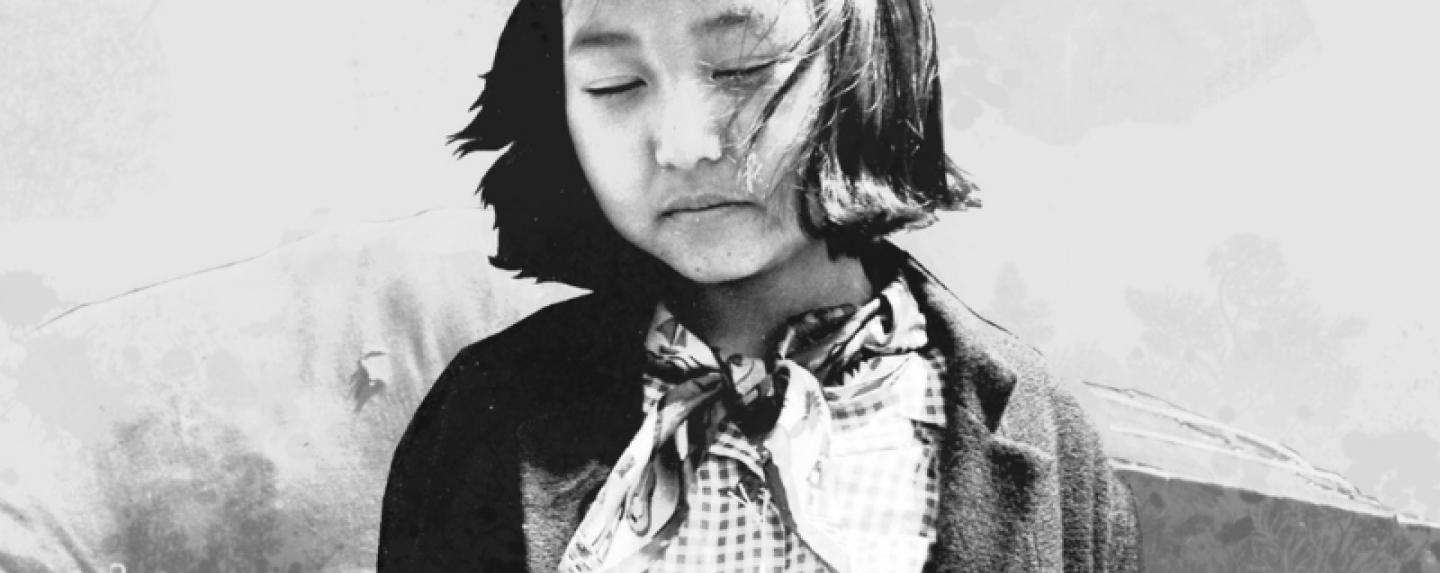

Click through to the PDF below for a classroom Thinking Routine activity using this image from the Densho archives.

Zoom In: The purpose of this activity is to closely examine an image. This activity will take about 10 minutes.

Episode 4: Cameras

Pictures allow us to peer into the past, but those images are often far more complicated than what initially meets the eye. Photographs (and the people who took them) portrayed Japanese Americans as menacing threats, as hapless victims, as model Americans. But there were also covert acts of resistance playing out on both sides of the camera. In this episode, we talk about the visual record of WWII incarceration and the stories that unfolded behind the lens. About what you see — and what you don’t. See the full transcript here.

Discussion Questions:

- Photography was one way to document an experience in 1944. What are some other ways of documenting experiences today? If you had to document an experience, what form would you use?

- Why do you think the War Relocation Authority (the government agency that ran the camps) wanted to portray the incarcerees as “good Americans”? What is the contradiction/irony in this message?

- How did the portrayal of Japanese American incarcerees as “good Americans” help lead to the myth of Asians being the “model minority”? How has this myth influenced perceptions/stereotypes of Asian Americans?

- The podcast gives several examples of anti-Japanese propaganda used during the war. What are some examples of propaganda related to other subjects that you can think of (e.g. immigration, terrorism, crime, COVID-19)?

Lessson Idea:

See–Think–Wonder Activity: This thinking routine encourages students to make careful observations and thoughtful interpretations. It helps students stimulate curiosity and sets the stage for inquiry.

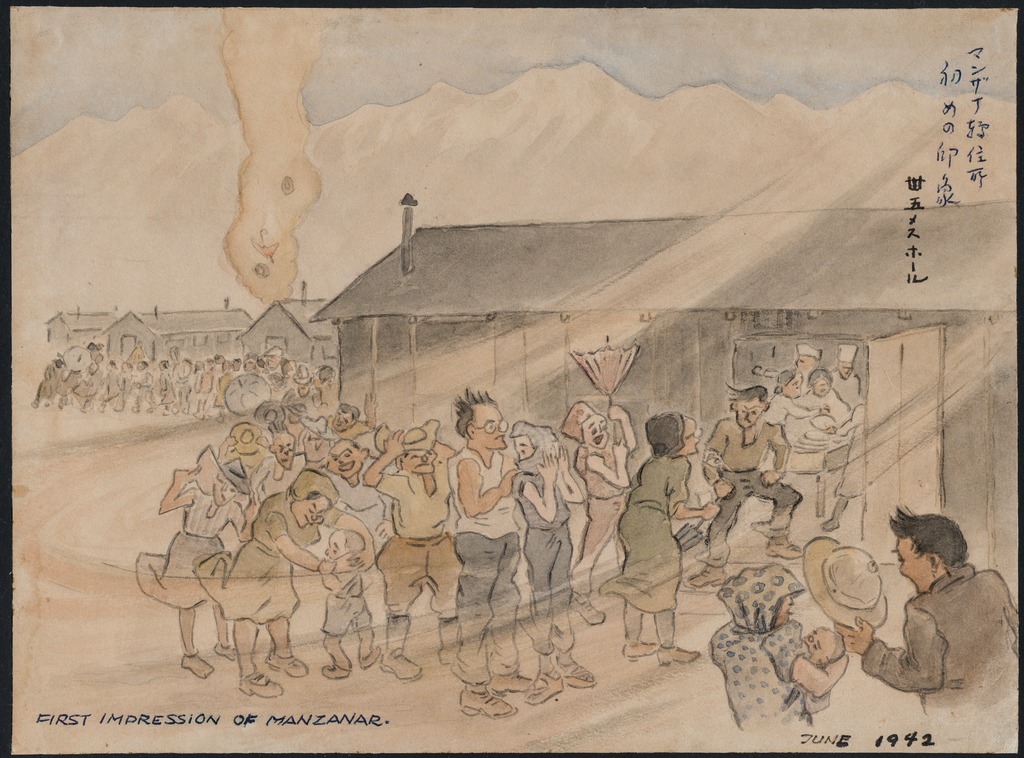

Show students this painting by Kango Takamura.

(Tip: Cover over caption in lower left corner that says, “First Impression of Manzanar.”)

Takamura was an Issei who was incarcerated at the Santa Fe internment camp and the Manzanar concentration camp. For more information on Kango Takamura, see the Densho Encyclopedia.

Ask each of the following questions in sequence, allowing time for students to look closely at the painting, to reflect, and to respond (either verbally or in writing) after each question.

Question 1: What do you SEE? (For this question, it’s important that students focus only on observation, not interpretation.)

Question 2: What does it make you THINK about? How does it connect with something else that you have seen or know?

Question 3: What does it make you WONDER? What questions does it bring up for you?

Episode 5: Latrines

In this episode, we talk about everything you never wanted to know about latrines in WWII Japanese American concentration camps. Our research may have gone down the toilet, but we promise this story isn’t all about poop. We’ll look at how incarcerees adapted to extremely adverse conditions and the unique challenges women incarcerees faced, including sexual violence and harassment. See the full transcript here.

Discussion Questions:

- How does the lack of privacy dehumanize people? In what other ways were incarcerees dehumanized? Can you think of other examples in history or in the present in which detained peoples have been dehumanized?

- Stories about sexual violence are often left out of the historical record — why do you think this is the case? Can you think of other types of stories that might be left out? Is it important that we try to uncover these stories? Why or why not?

Lesson Idea:

Think about all the infrastructure needed to accommodate 120,000 people in 10 concentration camps. Imagine that you work for the War Relocation Authority and that you are charged with setting up a camp for 10,000 men, women, and children in the middle of the desert. Working in a small group with other students, brainstorm a list of infrastructure needs for your camp. Think about basic needs, such as food, clothing, and shelter, as well as other needs like health care, sanitation, safety, education, and

recreation. How would you meet these needs?

Episode 6: Food

Food is more than just sustenance. It’s a vehicle for culture, a way to delight in the world around us, engage our senses, connect with other people. It’s how we tell someone we love them. It’s the lessons we pass down between generations—and the ones we don’t. This episode is about food in Japanese American concentration camps. It’s about mutton, so much mutton…but it’s also about disrupted traditions, about memory, about politics, and about subtle—and not so subtle—acts of resistance. See the full transcript here.

Discussion Questions:

1. What’s a question that you would like to ask one of your ancestors who has passed away? Why is this question important to you?

2. What is a culturally significant food or food memory for you? What does that food signify to you? How do (family) relationships tie into the food?

3. In this episode, several incarcerees talk about the horrible smell of mutton. Tell about a food scent, either good or bad, that takes you back to a particular time or place.

Lesson Idea:

Food is a core part of our daily lives but it is also an important part of how we transmit culture, memory, and identity. Now that you have learned about food in Japanese American concentration camps, take a moment to reflect on the significance of certain foods in your own life.

[Note: This activity may be triggering for students who are experiencing food insecurity. One alternative may be to start by asking, “How many of you have ever eaten food in a cafeteria or other institutional setting? What was the food like? Is there any particular food that stands out for you? Most students, even those experiencing food insecurity, will be able to relate to the topic of school lunches.]

Ask students to choose a food that has special meaning for them. They can either write a food poem about it (see prompts and sample below), or write a poem about school lunches. Have students share their poems with each other.

For further educational resources:

- Densho Learning Center

- “Other”: A Brief History of American Xenophobia on TED-Ed

- Ugly History: Japanese American Incarceration Camps on TED-Ed

- What Does It Mean To Be An American? – Curriculum for high school and college students that examines what it means to be an American developed by the Mineta Legacy Project and Stanford’s SPICE program.