January 19, 2021

1921 likely marked the peak year of Nisei births in the continental US. So with the arrival of 2021, there are a whole host of Nisei artists, activists, performers, civil servants, and more born whose 100th birthdays are well worth commemorating. We’re kicking off the new year with a look back at some of these Nisei notables.

Given how the flow of Japanese immigration was shaped by racist immigration laws, it is not surprising to see that the number of Japanese American births rose continually through the 1910s, reaching a peak in 1921 before gradually starting to decline.[1] (More on those numbers, and how they contradict the common myth that “over half” of Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII were children, here.)

Nisei born in 1921 would have been around twenty years old when World War II dramatically changed the lives of all Japanese Americans. For young adults in particular, the events brought about by the war—which for many involved forced removal and incarceration, interruptions in higher education, “resettlement” in unfamiliar areas of the country, and military service—changed the trajectory of their lives.

Two Beloved Nisei Writers

Two of our best-known writers, whose careers took divergent paths, were born in 1921.

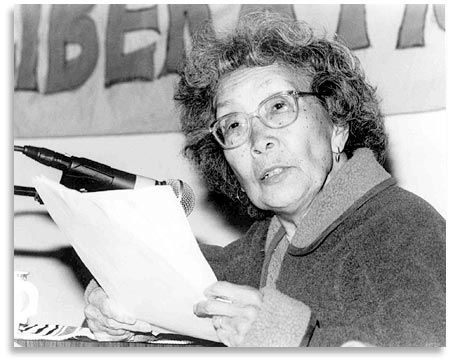

Hisaye Yamamoto DeSoto was from Southern California and was incarcerated at Poston during the war. After a stint with the Los Angeles Tribune, an African American newspaper, after the war, she published a number of short stories in prestigious literary journals and magazines mostly in the early 1950s. She focused on family life in the ensuing years, while publishing stories in the holiday editions of the Rafu Shimpo through most of the 1950s-1970s. But she remained little known to both mainstream and Japanese American audiences until the 70s. With the rise of ethnic consciousness and Asian American Studies, her works began to appear in numerous anthologies and become the subject of much academic study and critical acclaim, with awards, a published collection of stories, and a TV adaptation. Even after her passing in 2011, she remains one of the most acclaimed of Nisei writers.

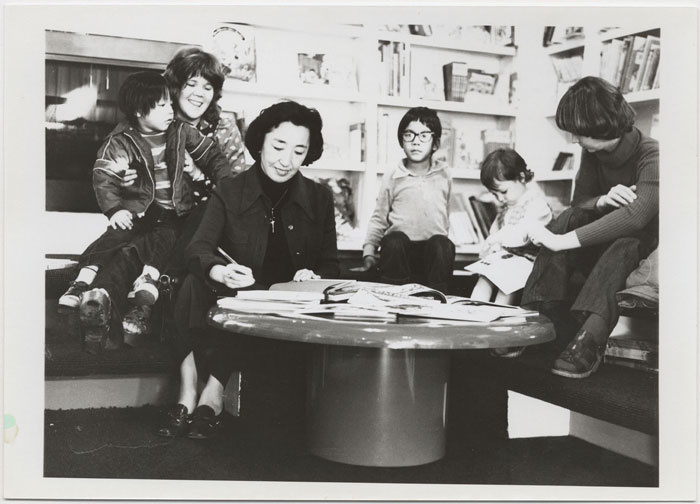

Yoshiko Uchida came from a prominent family in Berkeley and was attending the University of California when the war broke out. Eventually incarcerated at Tanforan and Topaz with her family, she left to finish her education back East, eventually settling in New York. While working as a secretary, she pursued creative writing, breaking through in 1949 when a collection of Japanese folk tales written for American children was published by Harcourt Brace. Over the next several decades, Uchida gained great acclaim and popularity writing children’s books set in Japan, and, later, that featured Japanese American characters. Her 1971 book Journey to Topaz, which was based on her family’s story, was the first children’s book about the incarceration by a Japanese American author. She went on to write several others. Her memoir Desert Exile, written in the 1960s, but not published until 1982, is one of the most cited of the Japanese American concentration camp memoirs. Uchida died fairly young, in 1992. Though well-known during her lifetime, she is perhaps less well-known today, though she was a key figure in making the story of the incarceration better known.

Nisei on the Stage and Screen

A couple of prominent Nisei entertainers were also born in 1921. Yuki Shimoda was from Sacramento and was incarcerated at the Sacramento Assembly Center and Tule Lake. He resettled in Chicago and, though he graduated with an accounting degree from Northwestern, he decided to move to New York to pursue his dream of becoming an actor. He subsequently became one of the few Nisei to attain mainstream success as an actor, landing roles in Broadway productions of Teahouse of the August Moon and Auntie Mame. He later moved to Los Angeles, working regularly in television and movies and appearing in two key movies about the Japanese American experience, Farewell to Manzanar (1976) and Hito Hata: Raise the Banner (1980). He, too, died young, at age sixty in 1981.

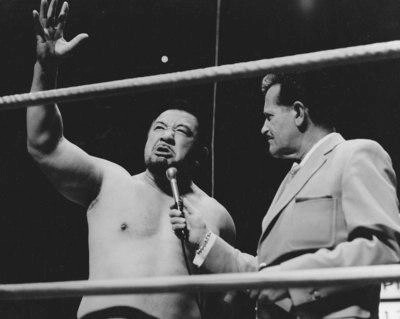

Kinji Shibuya was one of a group of Nisei who became stars as professional wrestlers when the sport—which was really a series of scripted exhibition matches—became a staple of the new television medium in its first couple of decades. Born in Utah as Robert Kinji Shibuya, he grew up in Los Angeles. He became a star football player at Belmont High School and later at Los Angeles City College in 1939–40 (as “Bob Shibuya”), while also starring as a basketball player in the Japanese Athletic Union. He moved to Hawai‘i in 1941 to join older brother Sam, who had also been a star athlete and who now ran a trucking business. He continued to play football at the University of Hawaii and semi-professionally.

After working various jobs in Hawai‘i, Shibuya was drawn into wrestling by a local promoter in the early 1950s and, with his wife Janet, moved to the continent in 1952 to pursue his new career. For the next fifteen or so years, he wrestled throughout the continent—the Midwest and Western Canada in the early years, California later on—with Janet and later two children in tow. As with the other Nisei in the business, Shibuya played a “Japanese” character that was inevitably a heel. He eventually settled in Hayward, California in 1967 and retired from wrestling in 1976. In retirement, he worked as an actor, ran an engine cleaning business, and raised koi. He passed away at age 88 in 2010.[2]

Unquiet Americans: Nisei Women Activists

Three notable Nisei women activists were also born in 1921. Yuri Kochiyama has become the best known and most celebrated of them, due in large part to the fact that her lifetime commitment to social justice inspired by her wartime incarceration mostly focused on groups other than Japanese Americans, something that resonates strongly today. Her transformation from sports-crazy San Pedro high school journalist in the 1930s to New York-based revolutionary in the 1960s—while also being a not atypical Nisei wife and mother of six—is a remarkable one that has captured the imagination of many and has been the subject of a memoir, a biography, and two documentary films, with more to come. We’ll have more about her life and impact around her birthday on May 19th.

Chizu Kitano Iiiyama and Setsuko Matsunaga Nishi lived somewhat parallel lives that balanced marriage and family life with paid work that helped support their families, and activism both inside and outside of the Japanese American community. Their stories also converged at Santa Anita and in Chicago in the 1940s.

Chizu Kitano Iiyama was born and raised in San Francisco, the fifth of seven children of Issei parents. (A younger brother, Harry H.L. Kitano, became a famed sociologist.) A student at the University of California when the war broke out, she was incarcerated at Santa Anita (the Iiyamas were part of the one small group from San Francisco that was sent there before Tanforan opened) and Topaz. She received her Berkeley diploma in the mail in May 1942 while incarcerated. She met her husband Ernest Iiyama at Topaz and the couple resettled in Chicago before moving to New York, where they were part of the Japanese American Committee for Democracy while running a dry-cleaning business.

After moving back to Chicago, Iiyama worked for the Chicago Resettlers Committee and as a social worker in the African American community, while she and Ernie were among those who formed a branch of the Nisei Progressives. The couple later moved back to Northern California in 1950s, where they raised a family, and Chizu—who had completed a master’s degree in child psychology at the University of Chicago—eventually became the first director of the early childhood education program in Contra Costa County. She remained politically active throughout her life both within and outside the Japanese American community, from the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s to the Redress Movement in the 1970s and 1980s. She passed away at age ninety-eight last fall.

Setsuko Matsunaga Nishi grew up in Los Angeles and was a student at USC when the war broke out and she was incarcerated at Santa Anita. Among the first Nisei to leave camp to go to college, she left Santa Anita for an M.A. program in sociology at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, moving on to a Ph.D. program at the University of Chicago upon her graduation. While pursuing her degree, she was active in the Japanese American community—like Iiyama, as a founder of the Chicago Resettlers Committee while also working with the African American community and two African American newspapers, in addition to marrying artist Ken Nishi and starting a family. The family moved to New York in the early 1950s, and in 1965 she became a professor of sociology at Brooklyn College, where she would remain for the rest of her academic career, while remaining active in the Japanese American community and in the civil rights arena generally.

Mettle and Medals: Prominent Nisei Veterans

A good number of the thousands of Nisei who served in the armed forces were born in 1921. Among them were two of the twenty-one Nisei who were awarded the Medal of Honor, the country’s highest military honor. Both of them—Yukio Okutsu of Kaua’i and George T. “Joe” Sakato of Colton and Redlands, California—survived the war and were among the group who were initially awarded Distinguished Service Crosses and upgraded to Medals of Honor in 2000.

Yukio Okutsu was from Kōloa, where his Issei parents ran a general store. Like many of his generation, he volunteered for military service during the war and ended up in the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team, as a platoon sergeant in F Company. He was cited for his heroism in battle in April 1945 on Mt. Belvedere in Italy.

Okutsu settled in Hilo after the war, where he became a parking meter mechanic for Hawaiʻi County and raised two sons with his wife Elaine. In retirement, he raised anthuriums. Journalist Karleen Chinen described him as a humble man who, when his award was upgraded to a Medal of Honor in 2000, “accepted [the award] with quiet dignity but was never really comfortable with [it]. Until the day he died in August of 2003, he remained simply Yuki the anthurium farmer.” In 2007, a veterans’ care home named after him opened in Hilo.[3]

George T. “Joe” Sakato also grew up as the son of Issei small business owners, in what is now called the Inland Empire east of Los Angeles. Facing war and impending forced removal, the Sakatos were among the 5,000 or so Japanese Americans who “voluntarily evacuated,” in their case to Arizona, where they had relatives. Sakato—who went by “Joe”—volunteered for the army and eventually went overseas as a replacement in E Company of the 442nd. He was cited for action on October 29, 1944 near Biffontaine, France. After the war, he settled in Denver, Colorado with his family and worked for the post office for thirty-two years. He did an interview for Densho in 2008 and died at the age of ninety-four in 2015.[4]

Frank “Foo” Fujita, a Nisei of mixed-race ancestry who grew up in Oklahoma and Texas, enlisted prior to the war and became one of the few Japanese Americans (outside of the Military Intelligence Service) who fought against the Japanese in the Pacific. He became one of just two Japanese Americans to become a prisoner of war of the Japanese Imperial Army, who held him for over three years. His wartime diary was later used to prosecute Japanese war criminals and was later published.

Many other Nisei veterans born in 1921 went on to postwar prominence in various fields.

Akira Otani‘s father, Matsujiro, ran a prosperous fish market in the ‘A‘ala district of Honolulu prior to the war, but was among the Issei community leaders arrested and interned after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Akira nonetheless volunteered for the Hawaii Territorial Guard and later for the fabled Varsity Victory Volunteers, eventually enlisting when the army opened back up to Japanese Americans. After serving in Japan during the occupation, he returned to Honolulu and, with his father, oversaw the expansion of the family business that eventually encompassed the country’s only live large-scale fish auction.[5]

Masato Doi was from the Big Island and was attending the University of Hawai‘i at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor and joined Otani in the HTG and VVV. He later served in the 442nd as part of the anti-tank company in Italy and France. Taking subsequent advantage of the GI Bill, he attended Columbia College and Columbia Law School before returning to Hawai‘i, where he became a lawyer, a legislator, and, eventually, a circuit court judge.

A surprising number of Nisei veterans also became artists. Two who were born in 1921 are sculptor Bumpei Akaji and graphic artist S. Neil Fujita, both of whom were from Kaua‘i.

Akaji’s exposure to paintings and sculpture while serving with the 100th Infantry Battalion in Italy inspired his own love of art, and he was able to remain in Italy after the war to continue his studies. He returned to Hawai‘i and lived most of the rest of his life there. Two of his best known sculptures—”VVV,” located at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and the “Brothers in Valor” memorial located at Fort DeRussy in Waikīkī—and are works of public art honoring the memory of the Nisei veterans.

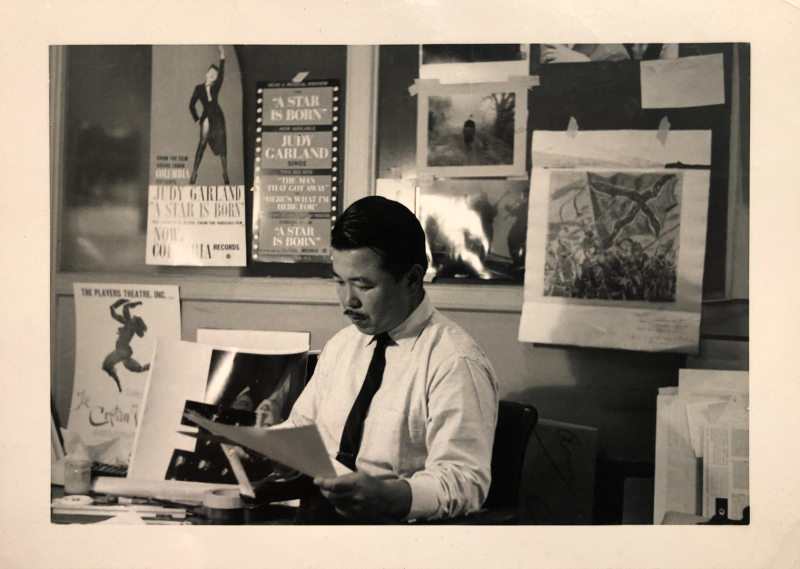

By contrast, Fujita spent most of his life in the continental U.S. Already in Los Angeles attending the Chouinard Art Institute when World War II broke out, he was caught up in the mass forced removal of Japanese Americans, ending up eventually at Heart Mountain. After serving in Italy and France with the 442nd, he returned to Chouinard and began a career as a commercial artist. He is perhaps best known for his stint as the director of design and packaging at Columbia Records in New York, where his jazz album cover designs incorporated the use of contemporary artists and abstraction, most famously in the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s classic 1959 album Time Out. In the 1960s, he led his own design studio that produced many well-known book covers, logos, and other designs. His story was among those featured in the recent documentary Masters of Modern Design: The Art of the Japanese American Experience.

And One Typical Nisei Story Gone Wrong

And finally, there is the story of Tomoya Kawakita, also born in 1921. While all of the people mentioned above might be viewed as “success stories” of one type or another, Kawakita’s can be seen as a typical Nisei story gone very wrong. From a relatively well-off family in Calexico, California (his father ran a trading company), young Tomoya was sent to Japan after graduating high school, where he attended Meiji University. This was not an uncommon path for Nisei who had the requisite ambition or finances, since there seemed to be greater opportunity in Japan for Nisei who could learn the language and culture, given the debilitating discrimination they faced back home, particularly in rural parts of California such as Imperial County. As was the case for many of the Nisei in Japan, his bilingual skills were in demand, and he eventually worked as an interpreter at a nickel mine in Kyoto Prefecture that used Allied POWs and Chinese and Korean forced laborers to work the mines.

Having survived the war, Kawakita returned to the U.S. in 1946. A few months later, he was recognized by a former POW in a department store in Los Angeles and accused of mistreating Allied prisoners who were forced to work at the mine. After a sensational trial, he was convicted of treason and sentenced to death, though he was eventually paroled sixteen years later on the condition that he return to Japan never to return. He lived out the rest of his life there. Though a compelling story, the Kawakita case has largely—and perhaps conveniently—been forgotten today.

These are just the bare outlines of the lives of a small sample of the Nisei notables born in 1921. Though these stories go in many different directions, I think there is a throughline of racism and war with the country of their ancestors, and how best to respond to being in such a situation. There are undoubtedly lessons we can take from these stories that are applicable today. At any rate, there are Densho Encyclopedia articles on most of them, so please click over if you want to learn more.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

[Header image: Birthday party c. 1956. Courtesy of the Okano Family Collection, Densho.]