October 22, 2020

Historical accounts of Japanese American incarceration often pay far more attention to the beginning than the end. But the scenes of camp officials hustling bewildered inmates onto trains in late 1945 bear a striking resemblance to the forced removal from the West Coast just three years earlier. Michi Weglyn colorfully described this time as “an incredible mass evacuation in reverse.” Minidoka, Densho’s “home camp,” closed on October 23, 1945. The story of those final days is as ironic as it is tragic, and was typical of what took place in each of the remaining WRA concentration camps.[1]

That story starts at the end of 1944, when the War Department lifted restrictions on the West Coast and announced that Japanese Americans could now return to their former homes. Shortly thereafter, War Relocation Authority Director Dillon Myer announced that all of the camps would be closed by the end of 1945. This news threw many inmates into a panic.

On the surface, this reaction seems strange. Why would people not want to leave the camps where they had been imprisoned for the last three years?

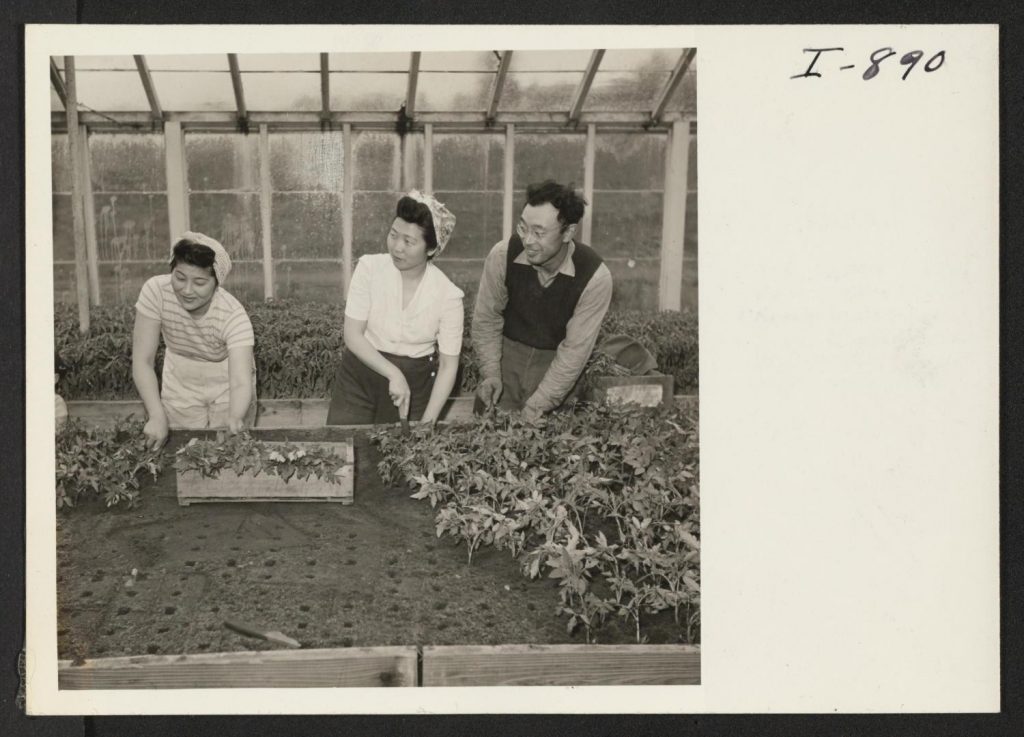

A lot of this had to do with who was still left in the camps by 1945. The WRA encouraged Japanese Americans it had defined as “loyal” to leave in order to resume a normal life as soon as possible. Many did leave the concentration camps for jobs, education, or military service in areas outside the West Coast restricted area, mostly in the mountain states, Midwest, and East. By the beginning of 1945, around 38,000 Japanese Americans had left the camps, about a third of the total number who had been confined. But that still left nearly 80,000 in the camps who had to be out in less than a year.

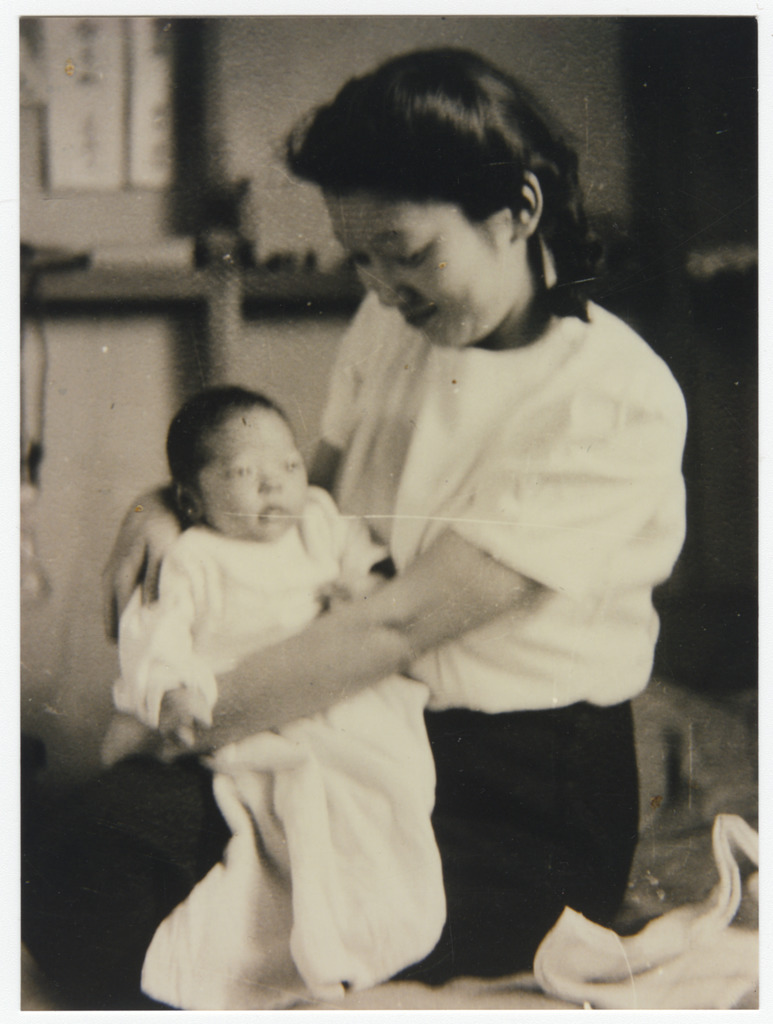

Furthermore, the demographics of the two groups were very different. Whereas the group that had already left was predominantly made up of Nisei young adults, those who remained included a disproportionate number of older Issei as well as young families with children.

The Issei—particularly the men—were typically in their 50s or 60s, and many had lost everything due to the forced removal and incarceration and were too old to start over. Many were also bachelors due to immigration and anti-miscegenation laws. A constant stream of stories about anti-Japanese sentiment throughout the country, along with alarming stories of the reception that greeted early returnees to the West Coast, led many of the remaining Japanese Americans to be fearful of leaving the camps.

Though confined, they were at least provided three meals a day and roof over their heads. And with nothing to return to, how would old men and families with young children support themselves and find a place to live in a hostile outside world?[2]

So at the beginning of 1945, the WRA was determined to close the camps by the end of the year—despite a substantial remaining population in the camps, many of whom were reluctant and afraid to leave.

“Encouraging”—and ultimately coercing—Japanese Americans to leave

January 1, 1945

296 days left

Population: 7,770 (83%)

At Minidoka, the population as of January 1, 1945 stood at 7,770—nearly 83% of its peak population of 9,397. This figure was perhaps artificially high, inflated by a large influx of 1,520 inmates who arrived from Tule Lake in the fall of 1943—a net population gain of over 1,000, since only 335 Minidokans left during that same time.

Over the course of the year, the administration worked to first encourage, then cajole, then force Japanese Americans out of the camp.

The “encouragement” part was pretty straightforward and similar to what took place at other WRA camps. In the fall of 1943, as segregation movements saw the relatively few “disloyal” Minidokans taken away to Tule Lake, what had been the Employment Division transitioned into the Relocation Division. The focus of the camp administration turned from building a community within the barbed wire to encouraging inmates to leave for the outside world. As early as the spring and summer of 1944, staff interviewers in the Relocation Division began a camp-wide project to interview the heads of all family units “to determine relocation plans and deterring factors appertaining to relocation,” though lack of staff kept this project from being completed.[3]

In 1945, the Relocation Division and the Reports Office began putting out weekly “Information Bulletins” to augment the camp newspaper. They focused on topics they hoped would encourage inmates to move out: Happy stories on former Minidokans seemingly doing well out in the world, information on available jobs and housing, and reprints of favorable newspaper articles, along with stories of white allies on the outside, all presented with an upbeat tone. A “Relocation Library” was set up in Block 22 and bulletin boards displayed job offers and outside housing information.[4]

One of the first manifestations of the closing was the shutting down of mess halls. In December 1944, the WRA headquarters in Washington, D.C., had issued orders for any mess halls serving fewer than 125 people to be closed. Mess halls that served less than 150 were “recommended” for closure. Under these orders, two mess halls—those in Blocks 22 and 32—were to be closed by March 1. Announcement of these closures spurred immediate resistance by inmates.

While the inmate community council asked camp director Harry Stafford to request an extension from the WRA, the Doshikai (Mess Hall Workers Association) organized a work slowdown at the end of February that saw meals served an hour or more late at most of the mess halls. This disrupted camp life by making inmate workers late for work and schoolchildren late for school. The slowdown lasted only a few days, called off, according to the camp newspaper, over concerns raised by the PTA. Mess halls were back functioning normally by March 1.[5]

Two other events of note took place in February. Minidoka was among the seven camps that sent representatives to the All Center Conference held at Topaz from February 16 to 22. The conference focused on the closing of the camps and resulted in a joint statement that tried to reconcile the varied and conflicting views of the delegates. During the conference, WRA Director Dillon Myer came to Minidoka, meeting the inmate leaders and speaking to around 1,500 inmates on February 19. According to James Sakoda, a Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) fieldworker in Minidoka, he made his case as to why the camps must close by the end of the year to skeptical audiences at both meetings.[6][7]

Navigating the “confusing, cumbersome, and expensive” process of relocation

March 1, 1945

236 days left

Population: 7,373 (78%)

The first inmates began to return to the coast in January and many were greeted with hostility. Reports of fire bombings, arson, and shootings began to filter back to Minidoka—along with rumors of other incidents that turned out not to be true—feeding into inmate fears of what would greet them on the outside. Many also refused to believe that the WRA would really close the camp and force them to leave.

Nonetheless, a small but steady stream of inmates did begin to leave: about 500 in March, a few less in April, then 725 in May. Meanwhile, the administration announced the closing dates of the schools—May 18 for the elementary schools and June 1 for the high school—which would end the education program. To ensure inmates understood that school would not be coming back in the fall, a Minidoka Irrigator article noted that teachers would be leaving for outside employment, with some being reassigned to other duties in the camp. Also in May came the announcement that some “cots, blankets, cooking utensils and so forth” were being sent to Seattle and Portland for use in hostels for returning Japanese Americans.[8]

While the WRA continued its push to get inmates to leave, the process remained cumbersome. In addition to having to arrange for housing and jobs and possibly welfare assistance, inmates had to also arrange for the packing and transport of their possessions, and navigate various offices to seek clothing allowances, travel allowances, and other forms of aid if necessary. “It was necessary for the relocating person to go to nearly as many buildings as there were steps in his process of relocating,” read one WRA report. “This of course, was confusing, cumbersome, and expensive.”

Navigating administrative politics and red tape was another major hurdle. In particular, the Relocation Division clashed with the Welfare Section, with the former pushing to get people to leave as quickly as possible, while the latter, in efforts to stretch available funds, required piles of time consuming documentation before granting assistance.

Inmates also had to make their own travel arrangements. So-called “special” cars or coaches—essentially train cars that were reserved for Minidokans only—were sought after by both inmates and administration, since they seemed to offer at least a degree of safety and comfort. But the scheduling of the “special” coaches was irregular and they sometimes were canceled at the last minute, since troop movements always had first priority. Those leaving Minidoka took a bus to the Shoshone train station, about twenty-seven miles away, from which trains took them back to the West Coast or to destinations to the east. Especially in the last weeks of the camp, various administrative staffers met inmates at Shoshone to help with last minute details and make sure everyone got on the train.[9]

“Enforcing Relocation” under Administrative Notice 289

June 1, 1945

145 days left

Population: 5,615 (60%)

August 1, 1945

84 days left

Population: 4,330 (46%)

While some inmates continued to leave the camp, the hoped for rush of departures in the summer did not occur. Fewer left in June than in May, and at a July 10 staff meeting, it was noted with some alarm that only sixty-six people had left that week, “a record low mark in recent months.” Fewer still left in July. Barely half of the population had left by August 1, less than three months before the camp was to close, since the original November 1 closing date had been moved up to October 23.

Until the summer, WRA administrators assured themselves that they would be able to persuade all of the inmates to leave and that there would not be a need to force people out. But by the end of July, it became clear that this was wishful thinking.[10]

On August 1, in recognition of this problem—which occurred in all of the remaining camps—Dillon Myer issued Administrative Notice No. 289. Though all but unmentioned in scholarship on the camps, AN 289 proved to be a turning point in setting the course for how the WRA would empty the camps.[11]

AN 289 called on all inmates to make plans to leave their camp as soon as possible. Inmates were to be grouped into “A,” “B”, and “C” classifications. People in group “A” were those who had both a destination and date set. Those in “B” had a destination set, but had yet to set a date. And those in “C” had neither a destination nor a date. The administration would be empowered to issue “two-week notices” to those still in group “C” as of September 1. Inmates who did not make plans in the allotted two weeks “would lose their individual discretion in the matter and would be subject to the pleasure of the administration in setting a date and destination for them.” Those that persisted in not making their own arrangements would be issued a “three-day notice” by the Internal Security Department and the project attorney. “[A]t the expiration of the three days the evacuee would be forcibly ejected from the Project.”[12]

Thus empowered, the administration set to work. Meetings were set up in mid-August in each block and four person teams explained the procedure spelled out by AN 289. Speakers emphasized the advantages of making plans early, including the greater availability of aid, and the availability of travel slots that might fill up for those who waited until the last minute.

According to Project Attorney Frank Barrett, as of August 25, there were 1,257 people in group “A,” 1,498 in “B,” and 672 in “C.” Barrett wrote that those in the latter two groups “are being subjected to personal persuasion, all kinds of reasoning and some leaflets in order to get them into ‘A’ classification.” He remained hopeful that “there should be no enforced relocation” and that “the residents will voluntarily go out within the scheduled time”—perhaps wishful thinking, since he would be the one charged with dealing with the eviction cases.[13]

In the meantime, more of the thirty-five mess halls continued to close. After the two early closures in March, another closed in April, then three more in July, and eleven in August. Many inmates then had to make long treks to other blocks for their meals. The camp co-op began liquidation proceedings on August 1 with remaining merchandise reduced at least 10%. There was also talk about consolidating blocks, but Stafford decided not to do this, reasoning that the psychological impact of being the last family left in a block “might even make them decide to relocate.”[14]

Some Minidokans resist yet another forced removal

September 1, 1945

53 days left

Population: 3,218 (34%)

Despite the pressure applied, there were a good number of inmates who still resisted leaving. There were groups appealing to the American Civil Liberties Union and the WRA to reopen schools, and a group of about a hundred seeking a transfer to Tule Lake or Crystal City with the ultimate aim of repatriation/expatriation to Japan. Some families had sons or husbands/fathers in the army and wanted to remain in camp until they could help them move out and establish a new home. In at least one case, a commanding officer told a Nisei soldier that his family would be taken care of in another camp until his discharge. Community Analyst Elmer Smith told Sakoda about inmates who were refusing to sign travel grant applications because they believed this would relinquish their rights to any further claims.[15]

But the largest group consisted of the many Issei—as well as a handful of Nisei—who believed that Japan had won the war or that the war was not over. Sakoda had left Minidoka for Berkeley in March, but when he returned on September 28 to document the final weeks in camp, he encountered a remarkable number of such people. “There’s no sense in leaving right now because a military boat is coming from Japan in March to take us back. It’s better to stay here,” an informant reported hearing in a laundry room. There was a “Victory Party” in Block 6, news of a meeting in Block 19 to plan for the welcoming of Japanese officials—including collecting $2 per person in the block to prepare the welcome banquet—and reports of people signing up in Block 42 for $10,000 payments to be received from the Japanese government. The expected arrival of Japanese ships or visitors encouraged many such inmates to remain in Minidoka.[16]

With a stubborn group of “C” group people remaining, the first three-day notices were issued with an assigned leave date of September 22. The unenviable task of issuing and enforcing the notices was assigned to Project Attorney Barrett and Internal Security Division Head Kenneth Barclay, both of whom Sakoda portrays as being generally sympathetic to the inmates and who took on this task reluctantly. They selected a group of thirty-four to start with. Inmate internal security employees were dispatched to inform the group. In his weekly report, Barrett reported that these unfortunate messengers “were subjected to a heap of abuse, were called all kinds of names not the least of which was that of traitor to the evacuee group…. The I.S. Men were threatened with injury so they asked to be excused from further work with the No. 289 list.”

While half of the group did agree to make their own plans to leave, four eventually were evicted from the camp on the 22nd. Barrett reported that those escorting the recalcitrant inmates out of the camp and to the train station “struggled through the bitter name-calling of the crowds and generally took a lot of abuse,” adding that “no one served so far has given any semblance of cooperation.” This would be a harbinger of things to come.[17]

“Why can’t they wait a little longer when we’re leaving?”

October 1, 1945

23 days left

Population: 1,482 (16%)

As the calendar turned to October, the administration shut down more and more camp operations to increase pressure on those who remained. At the beginning of the month, all inmate employment was ended, including in such vital areas as the mess halls. Remaining inmates volunteered to help staff remaining mess halls and run the boilers long enough to provide hot water for showers and laundry. Sakoda himself reported that he helped to run the boiler in his block. Through these efforts food continued to be served, but the menus became monotonous—lots of eggs, macaroni, and beans—as the administration tried to clear food from the warehouses rather than make new orders of fresh meat and vegetables.[18]

The water was turned off in some blocks. Sakoda reported that “residents therefore made use of the fire hose and filled barrels in the latrine with water to be used in flushing the toilets.” In what can only be interpreted as examples of gratuitous cruelty, the administration on at least a couple of occasions shut off the water even as inmates were showering or doing laundry. Even in latrines that remained open, they took down curtains and dividers that had been put up in the women’s section. “One often hears the expression: ‘Hidoi koto o suru’ (They’re mean.),” reported Sakoda.

Through an informant, Sakoda noted the impact on these actions on one family:

“One lady with 5 children, all 5 years or less cried as she talked to Mrs. Okawa. ‘Why do they have to do a thing like this. There was plenty of hot water…. I have 5 children and have to wash twice day in order to have a sufficient supply of diapers. Now I have to carry my chamber pot all the way from Block 1 to Block 6. Why can’t they wait a little longer when we’re leaving on the 21st?'”[19]

As the closing date of October 23 neared, inmates continued to leave, some “voluntarily,” some not so much. Tsusuke Nakawatase, seventy-four years old and described by Sakoda as “a wizen old man,” was notable as someone who strongly resisted attempts to evict him. Prior to the war, he had been a farmer in Seattle’s Green Lake neighborhood. Though his wife and children had left camp and returned to their former home, the old man stayed behind because he didn’t believe the war was over and he refused to leave before then. Issued a three-day notice, three men came to get him on the 12th.[20]

According to Barrett, Nakawatase first hid and could not be found. Once found and taken to the gate where he was given his cash allowance, train ticket, ration book, and other paperwork, “he promptly started throwing them around” despite repeated attempts to get him to take the papers. Dragged to the train station, he told Sakoda and Smith that he didn’t know he was supposed to leave that day and that he had been getting ready to leave in a few days.

Unable to reach Barrett, Internal Security head Barclay or new camp director W. E. Rawlings (in the middle of all the excitement, Rawlings replaced Stafford, who had been the camp director since the beginning, on September 1, 1945), they and the other inmates at the station agreed that he should be allowed to return to Minidoka so that he could properly prepare to leave. But when the train arrived, policemen forced him onto the train, the money and other paperwork left by his side, his possessions to be shipped later. Later, Smith was able to confirm that Nakawatase had indeed been scheduled to leave on the 16th, but that he had nonetheless been served a three-day notice for the 12th.

A more typical case involving a family was that of the K’s. Yoshiko K. was a thirty-nine year old Issei woman with four children between the ages of eight and fourteen, with the husband/father separately institutionalized in a psychiatric hospital. The family had lived in Marysville and Newcastle (towns north of Sacramento) before the war, but since there were no accommodations there, the Sacramento WRA office arranged to send them to Penryn, a town they had never been to, on a train that was scheduled to arrive at 1:30 am. They didn’t know where the hostel was, whether the station would be open, and what they would do until the morning. No arrangement had been made for anyone to meet the family at the station. WRA staff were unable to rearrange the schedule nor provide any answers, and the family was sent off as scheduled on October 20.[21]

By October 15, all but 390 had left. Of that group, 76 had yet to set a date. There were five mess halls still open, with two set to close on the 21st, two more on the 22nd, and the last, in Block 24, to remain open to serve breakfast on the 23rd, the last day.[22]

The Yamauchis were among the last families to leave. Consisting of an Issei husband, Nisei wife, and three young children, they had run a barbershop before the war. Embittered by their treatment and blaming the WRA for their refusal to store their equipment, resulting in the loss of the equipment, Hatsuye Yamauchi refused to leave. After receiving a three-day notice to leave on the 16th, they were able to get an extension to the 21st, since they had not packed. On October 21st, they went into hiding. When found, Mrs. Yamauchi demanded a signed statement from Rawlings confirming the conditions in the last days of the camp—the closing of mess halls and latrines, and so forth—before she would consent to leaving. After an undisclosed run-in with WRA staff, both she and her husband were jailed overnight in Jerome (a nearby town) before being forced on the train the next day. Sakoda saw the family as they got off the train in Seattle: “The father and the children looked grave. Mrs. Yamauchi was all broken up. All the fight that she had shown until now was out of her.” The family ended up in the Methodist hostel in Seattle.[23]

There are many similar stories—most of them sad or tragic—leading up to the official closing date. Though the camp did officially close on October 23rd, there was a bit of fudging, as the last few inmates were moved to the hospital, where they remained until they were able to be moved out within the week. And with that, the story of one concentration camp came to an end.

The closing stories of the other WRA camps—besides Tule Lake, which had an entirely different story that was coming to another kind of climax—were similar. These closing stories have been largely forgotten, overshadowed by stories of resettlement, of war heroes, of “model minorities.” But the sad—and ironic—end of the WRA camps deserves to be remembered as the final chapter of a story that never should have happened.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

[Header photo: Japanese Americans boarding buses to leave Minidoka, c. 1945. Courtesy of the National Archives.]