CAMPU: Episode 3 “Fences” Transcript

VO: Hey, it’s Hana. If you like what we’re doing, subscribe, share, leave us a review on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you tune in to your podcasts. It really does help us out. Thanks!

[break]

VO: Henry Nakano had written a song.

HENRY NAKANO: Oh give me land, little land, under city skies above. Don’t fence me in. Let me be by myself in the city that I love, don’t fence me in. Let me be by myself in my little room, listen to the radio and Sinatra croon, send me to the city, but I beg of you goon, don’t fence me in.

VO: Well, a parody. Roy Rogers had a new record out, and it was on. the. beam. That means cool, in 1940s slang. Cole Porter had written “Don’t Fence Me In” in 1934. It topped the charts for eight weeks in 1944, after Rogers sang it in the movie Hollywood Canteen. And it was equally if not more popular with kids in the Japanese American concentration camps riddled across the nation.

HENRY NAKANO: We’re stuck into this fenced compound, surrounded with barbed wire. So—

MAY K. SASAKI: one of the things that I remember is hearing—

TSUGUO “IKE” IKEDA: One of the songs we used to sing—

HENRY NAKANO: a popular song in those days was—

TSUGUO “IKE” IKEDA: “Don’t Fence Me In.”

BO T. SAKAGUCHI: “Don’t Fence Me In,”

MAY K. SASAKI: “Don’t Fence Me In,”

[Chorus: Don’t Fence Me In.]

VO: The song seemed to speak directly to them.

IKEDA: Cut down those barbed wire fences so we could feel our senses.

IKEDA: used to be my theme song—

SADAKO NIMURA KASHIWAGI: And I tell people, when I hear that song, it has a different meaning for us.

VO: The barbed wire fence isn’t necessarily the fence that comes to mind when we think of American iconography. We picture the white picket fence that shelters white suburbia and its white American dreams. But beyond those fences are the barbed wire ones of a reality that goes against everything America imagines itself to be.

VO: In this episode of Campu, we’re going to talk about the barbed-wire fence, what it meant to the people it imprisoned—and those it kept out.

Theme.

VO: From Densho, I’m Hana Maruyama and this is Campu.

End theme.

VO: Before we get started, I want to give you a heads up: this episode will contain some explicit language and discussions of state violence, murder, and suicide.

[break]

VO: From 1942 to 1946, Japanese Americans made lives for themselves behind barbed wire. Some were born. Some died. Some fell in love. Got married. Divorced. And the backdrop to all of this was the fence.

GRACE KUBOTA YBARRA: the barbed wire fence and the guard in the tower is still in my mind’s eye after fifty years.

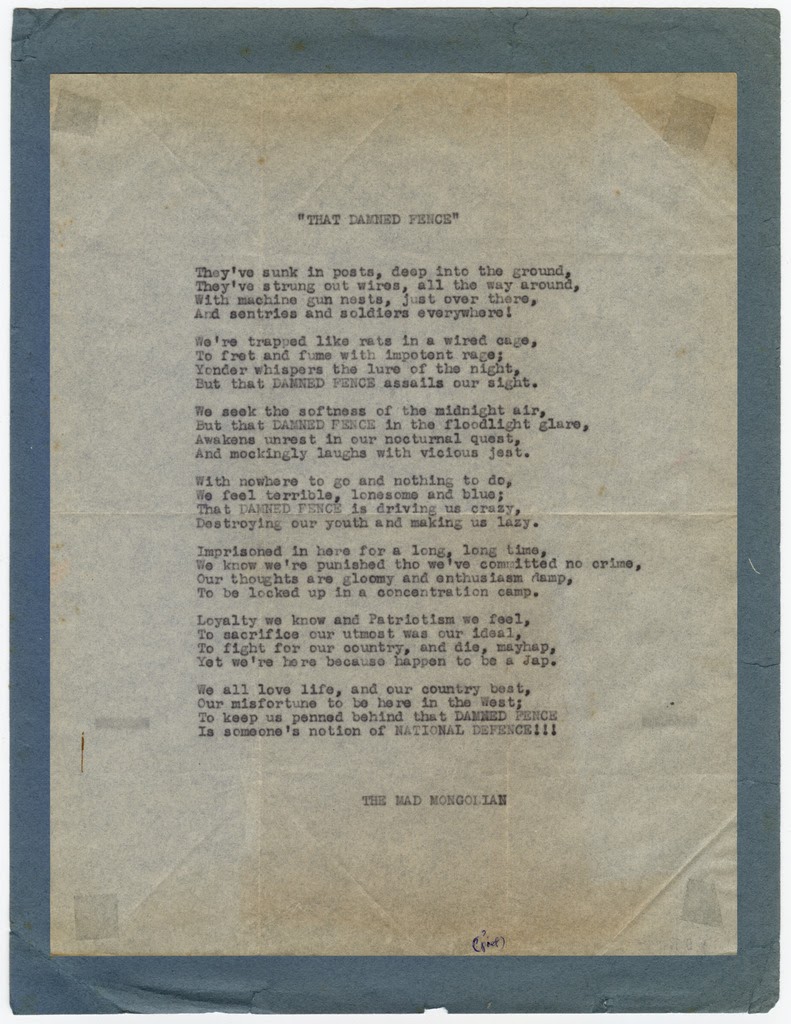

VO: It inspired great anger, as seen in “That Damned Fence,” a poem passed around anonymously among the incarcerees. There’s been a lot of debate about the origins of the poem. Over the years, it’s been attributed to several different people, including an individual who went by the name the “Mad Mongolian.” But when Holly Yasui saw the poem in a museum, she knew she’d seen it before.

YASUI: I had seen the TypeScript in my dad’s papers in which … he had put his name at the bottom of the poem.

VO: Holly’s dad was Minoru Yasui. You may recognize that name.

YASUI: He was in fact the first person to violate a military order leading to the forced removal and imprisonment of Japanese Americans.

VO: In March 1943, General John Dewitt instituted a curfew for all persons of Japanese ancestry.

YASUI: So he violated that curfew on purpose in order to bring a test case to the courts.

VO: Yasui took his case all the way to the Supreme Court. During this time, he was sent first to Minidoka, then to federal prison, then back to Minidoka.

YASUI: I remember him telling me he tried writing poetry when he was when he was in jail.

VO: Minoru Yasui was a renowned orator, activist and lawyer. But he only wrote poetry during his brief interlude in jail.

YASUI: …in all his papers, which ranged from the 1940s all the way to his death in the 1980s, I found no other poetry … and there are literally hundreds of thousands of papers … those are the only poems. It’s a little folder of about a dozen.

VO: By his own admission, poetry wasn’t exactly his genre.

YASUI: they were all pretty bad. He himself called his poetry doggerel.

VO: He didn’t publish the poem, though he did share it with his sister, nieces, nephews, maybe some buddies, Holly says. Still, the poem circulated at several camps—Minidoka, of course, but also at Poston and possibly Tule Lake.

YASUI: it’s like memes going, what do they call that, viral. It just hit the point… for a lot of young people.

VO: The reason Holly thinks that her father wrote it? Aside from finding a type-written version with his name on it–

YASUI: one of the versions of the poem in Densho is attributed to quote the Mad Mongolian. … that is a pseudonym that Min Yasui used for his doggerel.

VO: The confusion behind its authorship shows how much the poem resonated.

YASUI: what it does indicate to me is that, you know, there was a lot of seething, frustration and anger in the camps among all the nisei … And I think that the poem spoke to that.

VO: And it speaks to how the fence defined the incarceration experience.

YASUI: it was just there in your face, you know all the time. And … the fence is what made you realize you have lost your freedom.

VO: Here’s Holly Yasui reading an excerpt of the poem for us.

YASUI: Gosh how can I take on the Min Yasui persona? I don’t think I can.

He was quite an orator. Quite an orator.

That Damned Fence

They’ve stuck in posts deep into the ground

They’ve strung out wires all the way around.

With machine gun nests just over there,

And sentries and soldiers everywhere.

We’re trapped like rats in a wired cage,

To fret and fume with impotent rage;

Yonder whispers the lure of the night,

But that DAMNED FENCE assails our sight.

Imprisoned in here for a long, long time,

We know we’re punished—though we’ve committed no crime,

Our thoughts are gloomy and enthusiasm damp,

To be locked in a concentration camp.

YASUI: Min Yasui. It’s actually kind of hard. He didn’t have a very good sense of meter. [laughs]

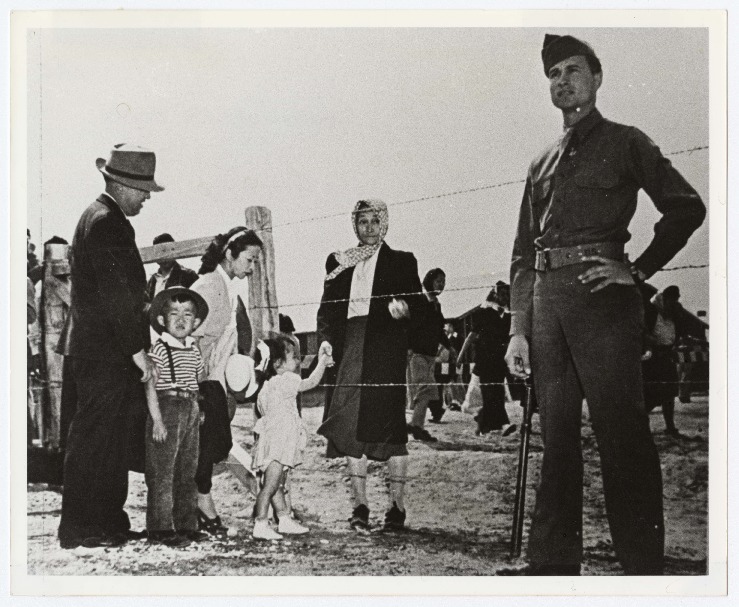

VO: That damned fence. It was the first thing that greeted incarcerees when they arrived at the assembly centers, the temporary detention facilities where Japanese Americans waited for more permanent “relocation centers” to be built.

AKIKO KUROSE: As we entered, I realized that there were barbed wire fences all around us.

MAY Y. NAMBA: four towers on the four corners … with the soldiers—

SEICHI HAYASHIDA: —they’re saying that these guards were to protect us—

BEN TAKESHITA: —to protect us.

MIN TONAI: —to protect us.

TAKESHITA: —armed guards and military police with rifles or submachine guns—

HAYASHIDA: —they didn’t have the guns pointed away from the camp … They were looking into the camp.

TAKESHITA: So we found out very quickly that this was not for our protection—

MASAO WATANABE: And quite frankly, I just thought, “What the hell is this?”

NAMBA: Then you knew you were prisoners.

KUROSE: I always considered barbed wire fences were to keep the cattle out of the [laughs] you know, farm areas … So that was pretty… interesting.

VO: In the assembly centers, the fence was often the only thing between the incarcerees and the city they used to live in.

CHIYE TOMIHIRO: they would stand outside the barbed wire fence and I would be inside and I’d be talking to them.

GENE AKUTSU: And when they would try to go up to the … barbed wire fence and try to shake hands, the guards would say, “Get away from there”—

NOBU SUZUKI: one of them brought a chocolate cake to us, but it had to go through the office. And when they brought it to us they had several slash holes in it, because they were afraid that they had put some contraband material inside the cake. [Laughs]

SHIGEKO SESE UNO: there were people outside looking in on the camp, as if we were the zoo.

TOMIHIRO: And you know, it was so humiliating.

VO: When they were transferred to the more permanent “Relocation Centers” further inland, they sometimes got a little more freedom—at least initially.

[desert ambience]

CHIZUKO OMORI: Our camp, as I remember … didn’t have barbed wire fences all around. … we could just go out. I mean, nobody stopped us because there was nowhere to go, you know.

BILL HOSOKAWA: … There was really no need for a fence. You could walk 20 miles through the sagebrush and not run into anything. And after the camp was pretty well settled, the army decided to put up a barbed wire fence around the camp and put up watchtowers.

VO: Some of the camps already had fences when the incarcerees arrived, but, sometimes, the fences were built weeks or even months after they got there. At Minidoka, some incarcerees saw the fence being built and—humiliated and angry—tried to dismantle it.

KATSUMI OKAMOTO: I heard rumors of first-generation Isseis, some of ’em going out and cutting it.

VO: In response, the contractor electrified the fence. The administration eventually apologized but also made sure to condemn the “destruction of government property.”

[end ambience]

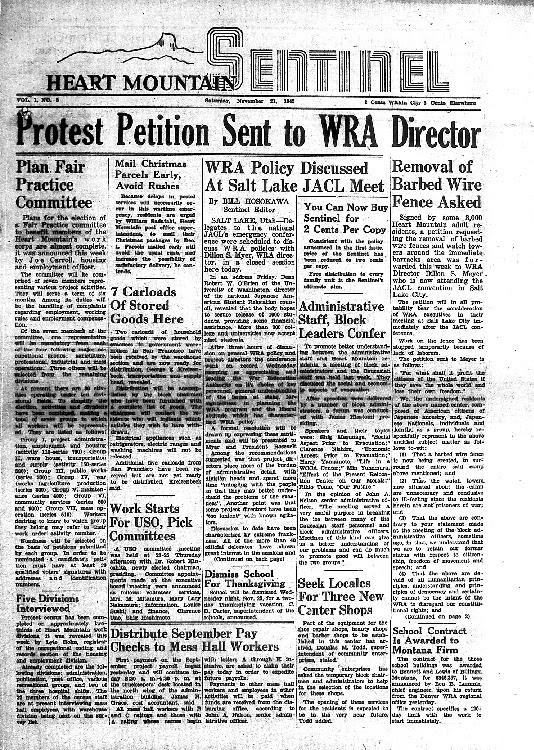

VO: At Heart Mountain, the fence was built in November, three months after the first incarcerees arrived.

BILL HOSOKAWA: some of the camp leaders organized a petition-signing campaign, as I recall.

VO: A petition went around calling the fence “an insult to any free human being.” Within a week, 3,000 incarcerees—about half of Heart Mountain’s adult population—had signed it.

BILL HOSOKAWA: the decision to build a fence was just the last straw.

VO: The War Relocation Authority, or WRA, did not respond. When the army tried to recruit incarcerees to build this new fence, the majority of working-age men went on strike.

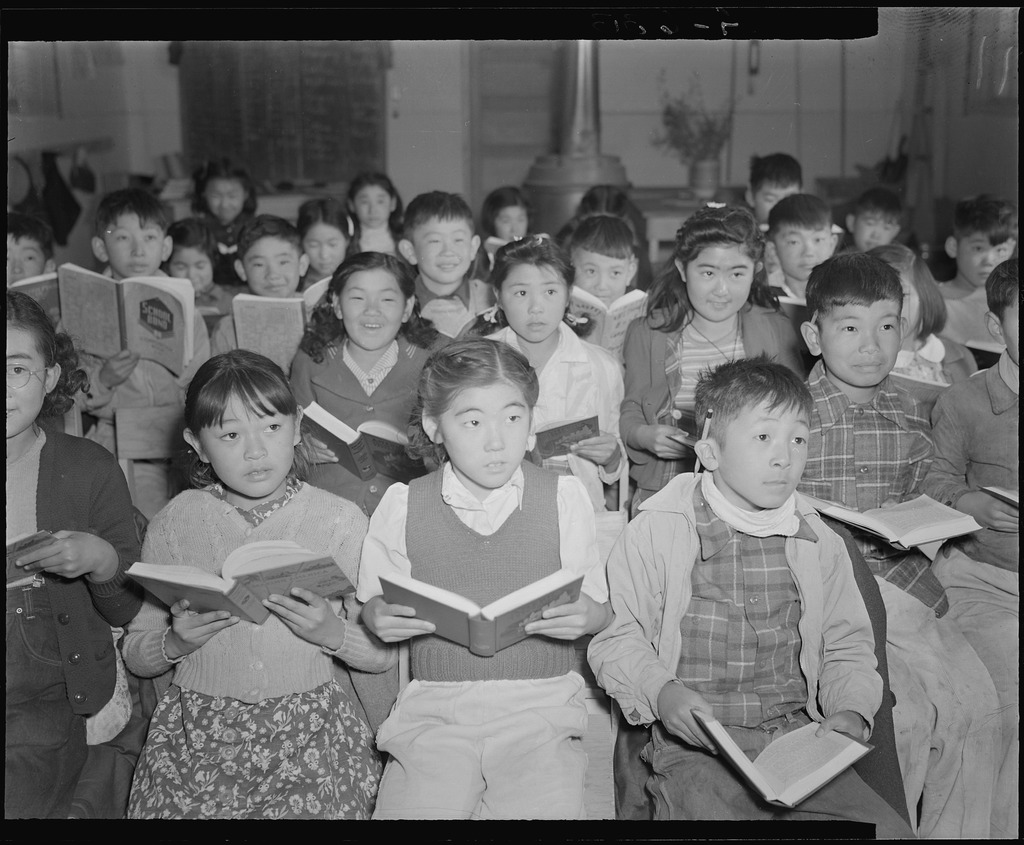

VO: Then, on December 2, 1942, the Military Police arrested 32 children for sledding on a hill outside the fence. The children were eventually released to their parents. Learning the rules of living behind barbed wire was… an adjustment. Frightened parents did their best to teach their kids to stay away from the fences. But kids didn’t always understand–let alone follow—these new rules.

CHIZUKO JUDY SUGITA DE QUIEIROZ: all the kids were told that we have to learn all the army words like … we had to learn the word “halt,” and “halt” meant “stop.” And never go near the fences, barbed wire fences, and never go near the sentry towers.

YOSHIKO KANAZAWA: my parents and other people told us, “You can’t get close to the fence or they’re gonna shoot you.”

KENJI SUEMATSU: they’ll shoot you there.”

GRACE KUBOTA YBARRA: she used to point to the guard up there and said, “You know, he has a rifle and he’s going to shoot you if you cross the barbed wire fence.” ….she said, “You know, there was a little old man who was collecting some rocks and he crossed the barbed wire and was shot and killed.”

VO: The story of the little old man who got shot and killed? That really happened.

BEN TAKESHITA: it was all ocean at one time … and the sand was filled with seashells and—

JUN KURUMADA: —he saw a seashell and he wanted to pick up that seashell–

VO: From our first episode, you’ll recall that collecting things—rocks, seashells, wood—was a popular pastime in camp.

BEN TAKESHITA: …he didn’t hear this guard saying, “Get away, get back, you’re too close to the fence”—

VO: James Hatsuaki Wakasa was 63 years old on April 11, 1943 when he was killed by a single bullet. Private First Class Gerald Philpott was in one of the Topaz guard towers some 250 yards away, and later testified that he meant for the shot to be a warning. Philpott was charged with manslaughter and went before a court-martial. He was acquitted. Mr. Wakasa was five feet within the fence when he was killed. An autopsy found he was facing the guard when he was shot.

TAKESHITA: The man was … possibly also hard of hearing and also concentrating, and so the guard just shot him dead.

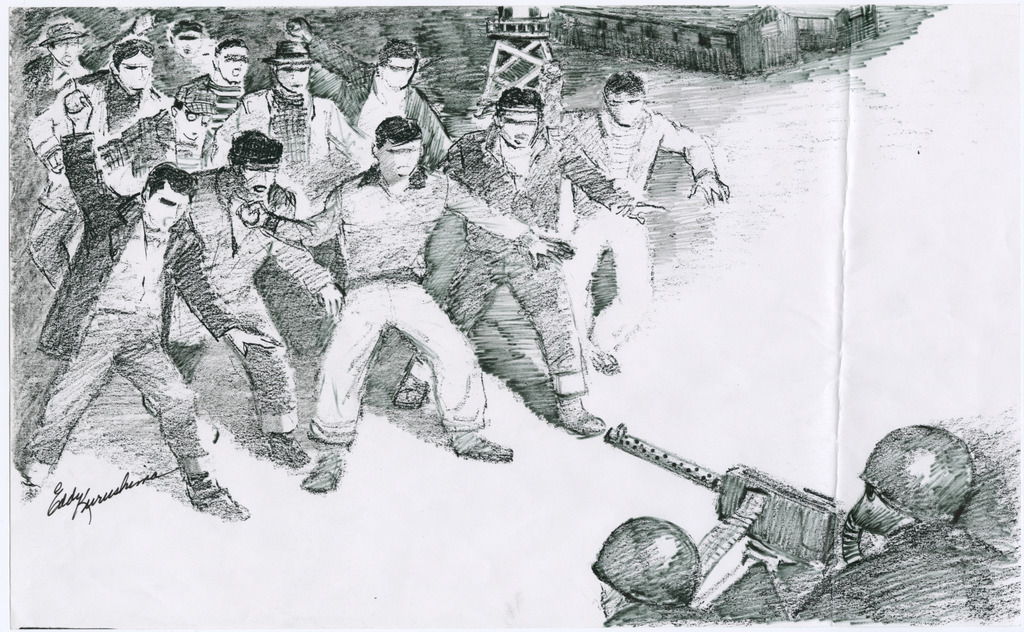

VO: At Manzanar, protests ensued in early December 1942 after the Manzanar WRA arrested three individuals suspected of beating a pro-WRA incarceree. One had been vocally against mismanagement by the administration. Hundreds gathered to demand his release.

VO: Military police threw tear and vomit-gas grenades into the crowd, leading to panic. In the commotion, some began to blindly run toward the police station, and some of the soldiers, without orders, fired upon the protesters. Nine were wounded. Two were killed. James Ito was 17 years old. Katsuji James Kanegawa was 21. These events later became known as the Manzanar Uprising.

GRACE SHINODA NAKAMURA: Yes, I was standing there and … Then from the guard tower they started shooting bullets and it hit Jimmy Ito, who was my classmate. He was standing right next to me and they just shot him dead. It could have been me, because they were randomly shooting.

NAKAMURA: He was just an innocent bystander, too.

VO: At Lordsburg, Toshio Kobata, 58, suffered from difficulties breathing after contracting tuberculosis more than a decade earlier.

WAKAKO YAMAUCHI: There was a guy named Obata-san. I think it was Kobata, but we used to call him Obata-san…

VO: On July 27, 1942, he was in a group of incarcerees who had just gotten off the train in Lordsburg, New Mexico. The station was 2 miles from the U.S. Army internment camp. Kobata quickly fell behind, as did Hiroto Isomura, 59. Isomura had suffered a spinal column injury decades ago. At some point during this walk, they were killed by Private Clarence A. Burleson. Burleson later testified, “these two men started running.” Two disabled, middle-aged men. The court martial acquitted Burleson on both counts.

VO: At Tule Lake, Shoichi James Okamoto was 30 years old when he was shot and killed by a guard.

KENGE KOBAYASHI: he was a truck driver working outside the fence, and … he has been going in and out, in and out every day so this guard knew him so he just waves him on. But, this one day this … new guard there who just came back from the Pacific war, he told him to halt. So he halted and he told him to get out of the truck so he got out, … and they started to argue and all of a sudden he shot him—

KENGE KOBAYASHI: —they said that they called the medics and everything, but this guard kept everybody away with the gun and so he bleed to death right on the ground.

VO: The guard was fined one dollar for the ‘unauthorized use of government property’—the bullet. He was acquitted of homicide.

VO: Kanesaburo Oshima was killed at Fort Sill on May 12, 1942. Mr. Oshima had been in debt before he was forced to leave his large family back in Hawai‘i. He was sent first to Sand Island Detention camp on Oahu. He was transferred to Angel Island, then Fort Sill in Oklahoma, all the while becoming increasingly anxious about his family.

MITSUHIKO H. SHIMIZU: [in Japanese with English translation] an old man went out of his mind and tried to climb up the fence. That happened right after I had finished breakfast. I found him trying to do that, so I ran toward him to stop him. I saw guards trying to shoot him, so I screamed, “Don’t shoot at him! He can’t cross over the fence anyway!” I told them just to pull him down because he was out of his mind. But they shot him down. I felt so sorry for him. Persons like him who went out of their minds were hospitalized for the time being, but they ended up being killed.

VO: Depression and anxiety were common among the incarcerees.

KAY UNO KANEKO: I remember my brother graduating from high school, … and thinking he would like to become a doctor, but here we are, we don’t know … what’s going to happen? And I remember he was very depressed, and he sat in one part of the camp in front of the fence, and we were afraid that he was going to try to climb over it or do something, make the guards shoot him or something. … a friend of ours gently talked him out of that, coming away, coming home.

VO: The fence could all too easily mean life or death. But it was also just a fixture of daily life. Half of the incarcerees were children. School in camp, like schools around the country, began with one thing.

JOHN NAKADA: we were in a concentration camp but every morning we had to say the pledge of allegiance to the flag—

SASAKI: …while being behind barbed wire fences—

TOSHIKO AIBOSHI: there was a patriotic fervor about the whole thing—

TORU SAITO: : We didn’t know what the hell we were saying. We just said what they told us to say—

AIBOSHI: We, of course, did the Pledge of Allegiance, but I remember learning all three verses and all the words to “The Star-Spangled Banner” and thinking I would memorize that to show my patriotism to the United States. That was how naive I was.

VO: Even the most patriotic felt the strain between honoring the America they loved and resenting their circumstances. Min Yasui, in “That Damned Fence,” for one.

YASUI: I mean, it’s this really interesting combination of both being angry and frustrated at the situation, but also affirming this … what I would call almost fanatical patriotism, which my dad definitely had. He was super, super patriotic.

VO: Here’s Min Tonai, a veteran.

MIN TONAI: today they play the Star Spangled Banner, I stand up and I sing it. “Pledge of Allegiance,” I say it. In camp, I thought it was ironic—

[MP4]

VO: For some, the rift between them and America would never be repaired.

SAITO: …since I left camp I cannot make, I cannot make myself say those words. They just can’t come out, you know?

PAUL TAKAGI: …I never, never salute the flag.

PAUL TAKAGI: “One nation indivisible—”

TORU SAITO: “With liberty and justice for all,” what a bunch of bullshit.

VO: Some had never realized that they were any different from other Americans. Dennis Bambauer grew up in an orphanage until he was eight. His mother was Japanese American and his father was white. In 1942 he was removed to the Manzanar Children’s Village. Anyone with more than 1/16th Japanese ancestry was subject to the removal.

INTERVIEWER: Did you have any sense of why you were being taken to this place?

DENNIS BAMBAUER: None whatsoever. I didn’t learn that until later when we were taught the Pledge of Allegiance. It was about that time … that I realized that I was there because I was part Japanese.

VO: He was not the only one who came to this painful realization in camp.

CHIZUKO JUDY SUGITA DE QUIEIROZ: […] after a few weeks … I came running home. And I said, “Lil, Lil, … Everyone in this camp is Japanese. Did you know that?” And I thought I had made the most fantastic discovery, and everybody would just be so astounded to hear this news … . And then she said, “Well, Chizu, this is…” [cries] … she said, “You know, we’re all Japanese Americans here, and we were put here for this reason.” And … she said that, “They think we’re the Japs … but we’re really Americans,” and I don’t want you to forget that. … and the whole thing sort of came together … and I thought, “Oh, my god, I’m a Jap, I’m a Jap.”

VO: Draft age men had received this message loud and clear after Pearl Harbor.

FRED SHIOSAKI: Being a very naive and dumb kid, I thought, “Well, I’m no different than those guys, and I expect to be drafted.” And so—

PAUL BANNAI: …I went up to the draft board and I said, “Well, here I am. The war is on. You’re calling everybody.” And they said, “You are now reclassified. You’re 4-C.”

FRED SHIOSAKI: 4-C.

GEORGE KATAGIRI: 4-C … the classification for “enemy aliens.”

SHIOSAKI: Even now, I’m mortified by it, just being classified an “enemy alien.”

VO: As we discussed in episode 2, the federal government began to recruit Nisei volunteers for the army in January 1943. What we didn’t get to in that episode was that a year later, in January 1944, the Nisei draft classification changed to 1A, which meant that eligible Nisei men could be drafted. They could now be compelled to serve in a segregated combat unit for the US Armed Forces while the same Armed Forces aimed guns at their families back home.

RANDY SENZAKI: my father volunteered for the service right after Pearl Harbor, and he was classified as an “enemy alien.” They wouldn’t take him … And so then when he was put in the camps, they came around and tried to draft him. And I was already born, and he was very bitter. He said, “When I volunteered, you didn’t want me, now I have a family behind barbed wire and you are asking me to go now?”

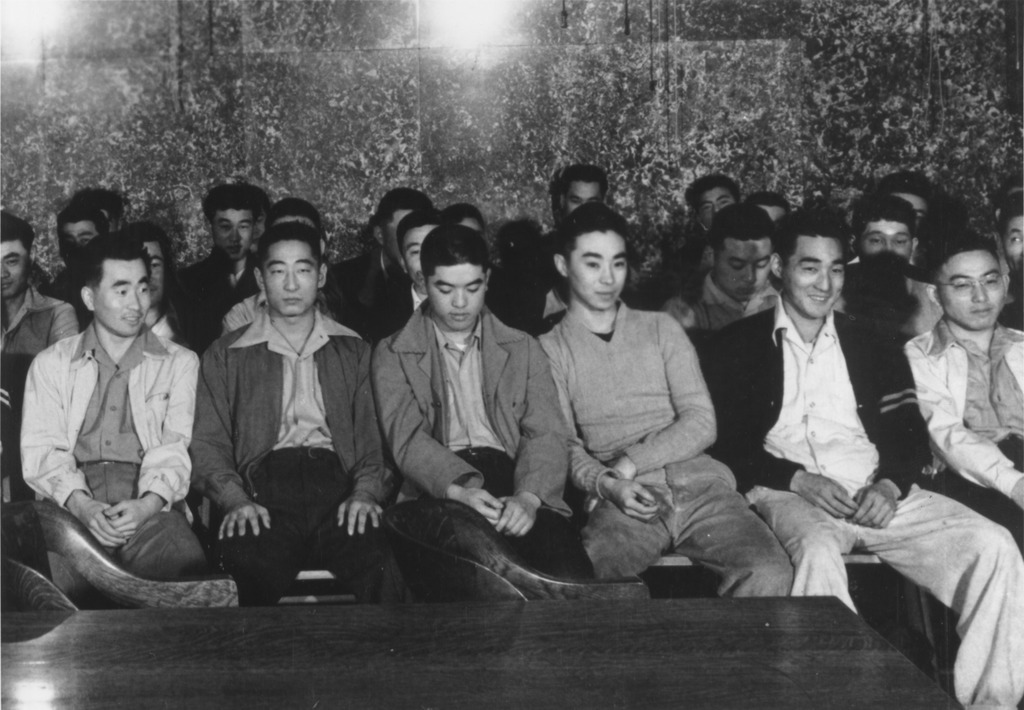

VO: Most Nisei complied with the draft, but some—nearly 300—felt that they could not fight for this country while it continued to incarcerate their families. Here’s Mits Koshiyama, a draft resister from Heart Mountain.

MITS KOSHIYAMA: how can I as a Japanese American citizen, be put into camp, denied my constitutional rights, denied my day in court to prove that I’m innocent, and yet I’m supposed to go out and volunteer or be drafted into a segregated army unit to fight for the very democratic principles that are denied me. I said, why should I go fight … for the very people that are oppressing me—

VO: Heart Mountain had the largest organized draft resistance movement of any of the camps. They demanded that the federal government release Japanese Americans before they would comply with the draft and brought a test case before the courts. For that case, they needed to prove that they could not leave camp. Here’s an interview with Frank Emi, one of the organizers.

FRANK EMI: we wanted to make sure that we established the fact that we were not free. And that’s the reason we … tried to walk out and then the MP stopped us and said if we kept walking he would shoot us.

VO: For many years, they were dismissed as cowards by their own community. But they felt they had to take a stand.

YOSH KUROMIYA: Somebody had to say somethin’.

KUROMIYA: we saw this as an opportunity to raise the issue; not to just get out of the draft just to save our own necks.

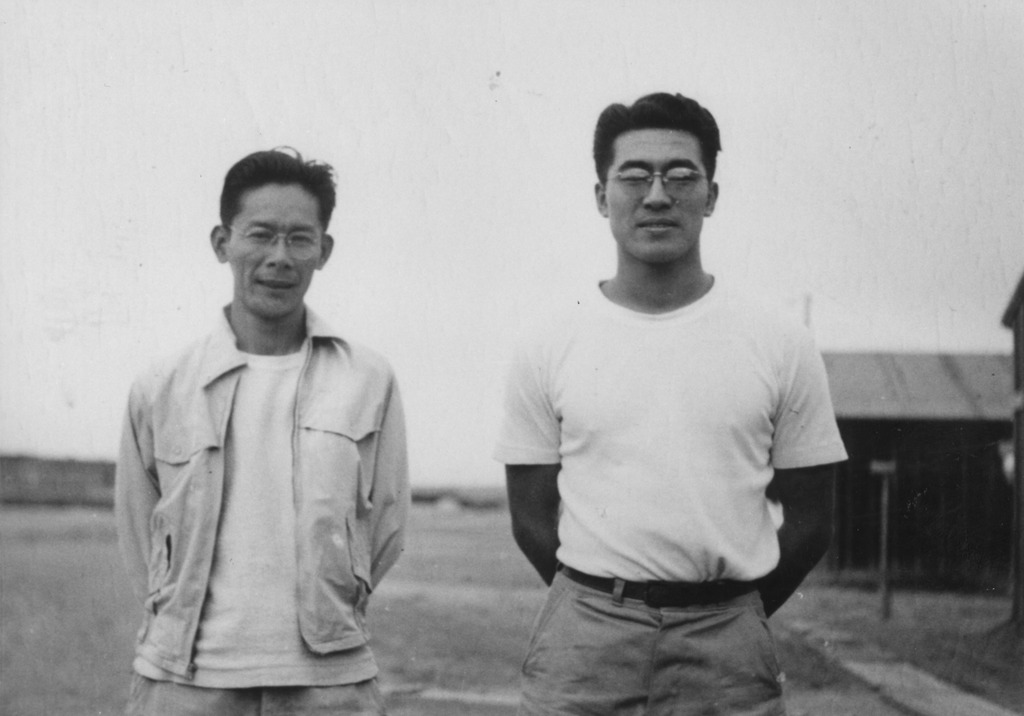

VO: Frank Yamasaki was one of the draft resisters at Minidoka. He’d had tuberculosis before the war. If he’d shown up for induction, he wouldn’t have passed the physical. For him, it was never about evading the draft. He wanted to make a point.

FRANK YAMASAKI: my anger built up and I says, “No, this is wrong. We don’t have to prove we’re Americans.”

VO: A few of the resisters did end up serving–just not in World War II. Tak Hoshizaki was just 18 when he was drafted–one of the few resisters young enough to still be eligible for the draft during the Korean War.

HOSHIZAKI: there were six of us in the group of sixty-three who then served during the Korean conflict.

HOSHIZAKI: they were drafting people into the army and I got my second draft notice, and … then I went into the army.

VO: Like he had promised, he fought when he and his family had been released. But these personal ethics didn’t matter back in 1944 and 1945. By the time the trial began in June of ‘44, 63 had been arrested. There were so many Heart Mountain resisters that there wasn’t room for them in the local jails. They were moved all across the state. Hoshizaki was sent to the jail in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

TAK HOSHIZAKI: it was probably never really cleaned, and so when all of us were then … stuck there before the trial, volunteered to clean up … so they told the guards to give us a bunch of rags … and then we scrubbed the whole place clean. So for the rest of the time we had a halfway decent place to sleep. In fact, some of us were sleeping on the floor because we were just jammed in there.

VO: The Heart Mountain resisters’ trial remains to this day the largest mass trial in the state of Wyoming. The presiding judge was T. Blake Kennedy and… let’s just say he was not impressed by the resisters.

MITS KOSHIYAMA: Well, the first day we went to trial, the judge called us “Jap boys.”

VO: Not too inspiring.

TAKASHI HOSHIZAKI: “Well, that doesn’t look good for us,”

MITS KOSHIYAMA: Things don’t look too good.

VO: Kennedy sentenced them to three years in prison. Eventually 85 were charged with and found guilty of draft resistance at Heart Mountain. Seven leaders were also found guilty of counseling draft evasion and sentenced to two to four years in prison. Five of their convictions were overturned on appeal in 1945. Two were not released until 1947. The Heart Mountain resisters were sent to McNeil Island and Leavenworth federal penitentiaries. Hoshizaki was sent to the former.

HOSHIZAKI: since we weren’t hardened criminals, we were then sent out to the minimum security area, which was the farm. There we lived in dormitories. No barbed wire. Doors were open … And so the conditions were much, much better than the county jails and much better than the, what we called the main house, the main penitentiary.

VO: Resisters from Minidoka were also sent to McNeil. Instead of a mass trial, Minidoka resisters had their own separate trials and—because they couldn’t afford counsel—were assigned Boise lawyers to represent them. Here’s the assistance Gene Akutsu’s lawyer gave him.

GENE AKUTSU: the first thing he said was, “You’re a damn fool. I’ll be darned if I’m gonna help you at all. You’re up on your own, boy.”

VO: Another lawyer told the judge that he didn’t want to sit at the same table as his client, whom he saw as quote “a traitor to his country.” The judge—former Idaho Governor Chase A. Clark—believed the solution to the so-called “Jap problem” was to quote “send them all back to Japan, then sink the island.”

GENE AKUTSU: we got a rough deal, rotten deal.

VO: Resisters at a couple of the camps got more sympathetic judges. Judge Louis E. Goodman dismissed the charges against the Tule Lake resisters on the grounds that being subjected to the draft while confined behind barbed wire was—in his words—“shocking to the conscience.” In 1946, the judge sentencing the Poston resisters found them guilty—and fined them a penny as punishment.

VO: In some ways, the federal penitentiaries were very different from the camps. The resisters were separated from their families during this time. And, when their families were released and struggled to rebuild their lives outside of camp, the resisters couldn’t be there for them. But in other ways, they’d just traded one prison for another. And that says a lot about this country’s relationship with prisons. Remember what Dr. Erika Lee said in the first episode about the management of bodies under capitalism?

ERIKA LEE: with slavery and settler colonialism it’s about the management … of certain populations towards the service or in the service of a white settler nation. So we know that the slave codes and the forced exile of Native Americans is part of this management to control where people go, what rights they have and to keep certain opportunities, the best opportunities, for white settlers.

VO: Confinement has become one of the main ways the state “manages” bodies. And that’s clear in Japanese American incarceration. Three concentration camps were created on American Indian reservations. And the reservations themselves had been created to confine Native Nations.

SAVILLA: when they first … put us on reservations—you had to have permission to get off, and if you went off without permission you were jailed—

VO: That was Agnes Savilla, a Mohave member of the Colorado River Indian Community, in a 1978 oral history. She worked for the Tribal Council in March 1942 and was present when the Indian Affairs superintendent informed the Council they intended to incarcerate Japanese Americans on their lands. The Army had already started construction.

SAVILLA: They just looked at him. They couldn’t believe it. That was the first thing they said really: ‘Well the government’s doing it again: taking our lands!’

VO: The Council called a recess and went down to visit the site.

SAVILLA: My heavens, it looked like the whole thing was just being torn to pieces down there, the land.

VO: The Tribal Council empathized with the Japanese American incarcerees.

SAVILLA: ‘The white man is treating them just like he treated us.’ … they were sore—not at the Japanese, but at the authorities for getting them in here.

VO: The creation of these camps blocked off their access to the lands they had left.

SAVILLA: We lost the use of that land while they were in here. … I had an old aunt living at that end of the reservation. … she lived over there by herself. And … we couldn’t go through without a pass.

VO: It also undermined their sovereignty—their rights as Indigenous nations to make decisions concerning their people and their land. A month later, the federal government did exactly the same thing at Gila River. The Gila River Indian Community Council held out for six months before signing the lease agreement with the WRA in October 1942. But the first Japanese Americans had arrived at Gila River in July. The council only signed because the federal government was now threatening not to pay them any rental money for the land–on top of using it without their permission.

[break]

VO: The WRA created prison after prison in its management of confined Japanese American populations. In 1943, the WRA started to experiment with separating out so-called “troublemakers.” Tule Lake was just another of the ten WRA camps when the administration first jailed people who refused to answer the Loyalty Questionnaire. Then Tule Lake itself was converted into a segregation center to separate out those deemed “disloyal” from all the camps. And then the administration built a stockade to partition off those it considered most troublesome.

FRED TADASHI SHINGU: next morning the MP came through, started from one end of the camp, picking up everybody, … that’s when I was picked up and thrown in the stockade.

TOM AKASHI: He even locked up kids. Sixteen-, fifteen-years-old, … buddies of mine …

VO: Some asked the colonel in charge why they had been selected for this treatment—

K. MORGAN YAMANAKA: his response was essentially, “You’re here because you’re here.”

VO: His records were a little more forthcoming. “General troublemaker,” “too well educated for his own good,” “leader of the wrong kind.” These were just a few of the reasons these people couldn’t see their families and friends for nine months.

SHINGU: two guys that I used to work with and … I was trying to talk to them. He said, “No, I can’t, we can’t talk too much because there’s a guard up there looking down at us.” … even they didn’t want to talk to us because they might get shot…

YAMANAKA: I remember my mother coming to the end of the prison area, … where we were and waving. And then they put a plywood so we couldn’t see each other.

VO: Conditions in Tule Lake were bad. But the stockade was even worse.

YAMANAKA: having midnight raids in the barrack was nothing unusual.

SHINGU: they wanted a head count, so they line up right against the barrack.

YAMANAKA: there was about two hundred twenty people—

AKASHI: Holding prisoners for eight months without a trial, without a hearing, without charges.

TOKIO YAMANE: [in Japanese, with translation] The FBI and Dies Committee showed up randomly 24 hours a day and took anyone kept in the stockade to another place for individual interrogation.

YAMANAKA: I think that was about the only time in my life I was physically scared.

SHINGU: there was a Jeep with a gun pointed at us, machine gun pointed at us, and then another one. … Seemed like one was a tank.

YAMANAKA: we were told to get out in a open area of the closed stockade, and one of those times … the whole area … was already surrounded by soldiers in full uniform with their … rifles, and then by the gate there was a truck with a machine gun aimed at us with a guy sitting by the machine gun.

SHINGU: And both of the guns were pointed at the whole group there.

YAMANAKA: That Thompson machine gun was aimed at my belly …

SHINGU: So I thought what the hell are they gonna do? Are they gonna shoot us?

VO: The stockade was so bad that the incarcerees went on hunger strikes to protest its conditions.

YAMANE: [in Japanese with English translation] If we hadn’t done anything, we would have been locked up there for one full year. We didn’t know if or how long we would continue to be kept in the stockade after the one year milestone. We decided to go on a hunger strike to win unconditional release.

SHINGU: Two weeks, two weeks of not eating anything.

VO: Some of the more worrisome “troublemakers” were sent to Moab, Utah—a former Civilian Conservation Corps site—and then Leupp—a former American Indian boarding school on land belonging to the Navajo nation. When Harry Ueno was initially transported from Moab to Leupp, he and his group spent the whole ride in a box on the back of a truck.

HARRY UENO: that was 5 by 6, around that size, the box. About oh, four feet high. … a padlock on the back. They open and he picked the five people to go in there. And only small breathing hole in back…

VO: They were in there for the whole of the ten plus hour journey. Instead of taking them to Leupp, the truck took them to a jail in nearby Winslow, Arizona, but…

HARRY UENO: you know, it costs money to keep us in the outside jail. So they took ’em back to the Leupp Indian school there and they have a jail in down cellar. I imagine they used to put the Indian kids into the jail, you know.

VO: Why would they need a jail in a school? Well, these boarding schools weren’t so much schools as they were institutions designed to take children from their families and force them to forget their cultures. Not so different from a prison. So, when the school was converted into a prison a year after it closed, the jail in the basement was already there waiting for them.

HARRY UENO: So I was in with the other people in that jail for ten days, and finally I been released from there.

[break]

VO: From Reservations, to Plantations, to Boarding Schools, Prisons, Jails, Concentration Camps, Detention Centers—confinement has a long and distinguished history in the land of the free. Today, the U.S. imprisons more people per capita than any other country, in a system that disproportionately impacts Black, Brown, and Indigenous people. In the last few years, the image of the barbed wire fence has come to be associated with migrant detention. Tsuru for Solidarity, a Japanese American activist organization, leads protests against these current-day concentration camps. Mike Ishii is one of the organization’s co-founders:

ISHII: The earliest roots of Tsuru for Solidarity are really at the 2018 Tule Lake pilgrimage. … And if you remember, at that time, they were actually stripping children out of the arms of their parents at the border, and incarcerating children. So during the pilgrimage, we actually staged a protest right in front of the Tule Lake jail. Where all the survivors were present. There were people who were 96 years old, under blistering sun…

ISHII: the Tule Lake community were the people who actually stood up and resisted in that moment, and they were severely targeted for that.

VO: 75 years later, these same incarcerees and their families, are again leading Japanese American resistance, this time against migrant detention.

ISHII: So the historical roots of resistance in our community continue to guide us to this day.

VO: But as we’ve discussed in Episode 1, speaking about their experiences isn’t something that comes easily to many incarcerees, even decades later.

ISHII: Kiyoshi Ina … he’ll probably kill me that I’m talking about him, but he’s one of the most humble people I’ve ever met. And I know that it’s not easy for him to speak publicly. … He prefers not to. But he does it because he knows that it makes a difference for someone else if he speaks out.

VO: Many Nisei were told not to make waves, to keep their heads down. A common saying in the Japanese American community at that time was “Shikata ganai.” It cannot be helped.

ISHII: at Fort Sill, you see Chizu Omori, you know who is 90, 91 now, I think, speaking out and standing up to that military guard. And this whole line of survivors just standing there refusing to be moved.

VO: These Nisei have joined with new generations of activists, inspired by their families’ experiences.

ISHII: Becca Asaki, another organizer in Tsuru, spoke at the Burke’s detention site when we went there several weeks ago to protest to release Haitian families. She said, I’m standing here in front of this fence. And I can’t imagine what it would have been like for my family if people had come to their fence to demand that they be released.

VO: Japanese American elders, often children themselves in the camps, know how this experience can affect children for the rest of their lives.

MARY NOMURA: my nephew said that he … was doing something and something fell over on the other side of the fence, and … my nephew went through the fence to go get it, and a sentry came down and took his bayonet, hooked him up by his suspenders, and put him back over the fence. And my nephew says that was something he didn’t have to do, to scare the daylights out of a little kid. He must have been about … seven.

VO: Being incarcerated shaped their worldview from a very young age, in big ways and small.

KAZIE GOOD: She was a child, seven when she went in, ten when she got out. And the first time we got off the bus, she looked around and she said, “This town doesn’t have a barbed wire fence around it.”

KAZIE GOOD: those were things that just stuck in my sister’s mind, and she just thought that’s the way the world was.

VO: Other Nisei have experienced firsthand the trauma of being separated from a parent due to their arrest.

ISHII: they took away our our elders and put them in Department of Justice camps sort of similar to how ICE is rounding up people out of communities. It’s so resonant of those raids that the FBI did on our community, right after Pearl Harbor.

VO: Mako Nakagawa’s father was arrested by the FBI after Pearl Harbor.

MAKO NAKAGAWA: …we went down to the immigration office a couple times to see him. And so the story goes that one of the friendly guards teased me and slammed the bar gates closed and says, “Now you’re a captive. You have to stay here,” and kind of threatening me, just being funny. And apparently I ran to my father, jumped in his lap, and said, “Oh, good. I get to stay with Papa.” And that’s when Mama started kind of crying—

VO: On the day her father was being transferred to Missoula, Montana, Nakagawa recalls going with her mother and siblings to see him off.

MAKO NAKAGAWA: My father says he comes out and he sees us, and he doesn’t ask permission to come to the fence to talk to us.

MAKO NAKAGAWA: and all the while he’s walking there, he’s kind of expecting that someone is going to stop him.

MAKO NAKAGAWA: and then he looks and sees his wife and his kids and he doesn’t know what to say ’cause he was concentrating completely on just being stopped and so when he gets to the fence, he looks and then he’s really at loss for words.

MAKO NAKAGAWA: and he turns around and starts walking back to the train to get on. And then he says he hears the kids calling him, “Papa. Papa. Pappa.” They’re yelling to him. And forty years later when my father is so deaf that he can’t hear Japanese music anymore, he’s telling me that, “Oh, Mako,” he said, “I could hear my kids calling me.”

VO: Like Nakagawa and her father, children are being separated from their undocumented parents everyday in this country—sometimes on the same sites where Japanese Americans were incarcerated. Tsuru for Solidarity has organized protests at Crystal City in Dilley, Texas, and Fort Sill, both of which were used as sites of detention for people of Japanese ancestry during World War II.

ISHII: Lauren Sumida, who is another Tsuru organizer from New York … She had been doing some research and what she found out was that … After they closed Crystal City down after World War Two, they dug up that fence and they took it to Calexico which is the US Mexico border in California. And they repurposed it to build the wall of the border.

VO: The parallels with Japanese American incarceration are reason enough for outrage. The differences are horrifying. In 2018, the Trump Administration instituted a “zero-tolerance” policy which not only separated asylum-seeking parents and children, but also imprisoned the children in overcrowded, under-resourced facilities to be cared for by armed guards. Japanese American actor and activist George Takei wrote in an op-ed, “At least during the internment, when I was just 5 years old, I was not taken from my parents.” As Mako Nakagawa’s story shows, it wasn’t an uncommon experience for children to be separated from at least one parent. And some Japanese American children were separated from both parents–these children were sent to the Manzanar Children’s Village or shuffled around among foster parents and family friends. But these cases were rare. Highlighting these differences is important, says Ishii.

ISHII: in this moment now, no one’s gonna come knocking on our doors. They’re not going to do FBI raids on our community. They did that to us. And we carry the trauma of it. But we are not being targeted like that.

VO: And now, in the midst of an international epidemic, these groups—imprisoned in close quarters without access to proper hygiene—are at even greater risk. We’re going to talk more about the health issues presented in concentration camps in a future episode. For now, let’s just say there’s a reason why the fence keeps popping up, why it keeps being used against certain populations.

ISHII: it was just surreal to me to think about how across time and generation this idea of the fence keeps being repurposed to separate people and repurposed on communities of color … to deny us resource or equity or freedom.

VO: That’s why the image of the crane—the Tsuru—is so powerful, says Ishii. Tsuru for Solidarity collects origami cranes folded around the country.

ISHII: they actually contain the energy of care and protection that our community folded into them.

ISHII: And so I think as you’re hanging those cranes every time we go there … we transform the internal image of a barrier that separates people in our own minds and hearts.

[fade out on NAKANO: Oh, let me straddle my old rattle underneath the city skies. On my hop up, let me travel over gravel ’til I see the buildings rise. Oh, let me ride to the West where Hollywood commences, gaze at Betty Grable ’til I lose my senses, send me to the city but I beg of you please—”]

VO: Don’t fence them in.

VO: You’ve been listening to Campu. Subscribe, like, share, leave us a review—on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you tune in to your podcasts. Or just tell your friends. It really does help! Visit densho.org/campu for additional resources and this episode’s transcript.

VO: Campu is produced by Hana and Noah Maruyama. The series is brought to you by Densho. Their mission is to preserve and share the history of the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans to promote equity and justice today. Follow them on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram at @DenshoProject. Support for Campu comes from the Atsuhiko and Ina Goodwin Tateuchi Foundation. Special thanks to Natasha Varner, Brian Niiya, Andrea Simenstad, Naoko Tanabe, Mike Ishii, and Holly Yasui for their assistance with this episode. The interview with Agnes Savilla was used courtesy of the Lawrence de Graaf Center for Oral and Public History, California State University, Fullerton. This episode included excerpts from nearly 50 Densho oral histories as well as interviews conducted by Frank Abe for his film Conscience and the Constitution. The names of the narrators featured in this episode are: Henry Nakano, Tsuguo “Ike” Ikeda, Bo T. Sakaguchi, Sadako Nimura Kashiwagi, May K. Sasaki, Grace Kubota Ybarra, Akiko Kurose, May Y. Namba, Seichi Hayashida, Ben Takeshita, Masao Watanabe, Nobu Suzuki, Chiye Tomihiro, Gene Akutsu, Shigeko Sese Uno, Chizuko Omori, Bill Hosokawa, Katsumi Okamoto, Chizuko Judy Sugita De Quieiroz, Yoshiko Kanazawa, Kenji Suematsu, Jun Kurumada, Grace Shinoda Nakamura, Wakako Yamauchi, Kenge (Kenji) Kobayashi, Mitsuhiko H. Shimizu, Kay Uno Kaneko, John Nakada, Toshiko Aiboshi, Toru Saito, Paul Takagi, Min Tonai, Dennis Bambauer, Fred Shiozaki, Paul Bannai, George Katagiri, Randy Senzaki, Mits Koshiyama, Frank Emi, Yosh Kuromiya, Frank Yamasaki, Takashi Hoshizaki, Harry Ueno, Fred Tadashi Shingu, Tom Akashi, K. Morgan Yamanaka, Tokio Yamane, Kazie Good, and Mako Nakagawa.

Discussion Questions

- Consider the sayings, “The nail that sticks up gets hammered down” and “The squeaky wheel gets the grease.” What do you think each of these sayings mean? Which saying do you identify with? What is an example of each of these from the episode?

- To some, fences represent confinement and to others they represent safety. The American flag is another common symbol that has very different meanings for different people. Name two different things it represents to different groups, and then think about what it means to you.

Visit the Campu Education Hub to see full discussion questions, lesson ideas, and activities.