August 3, 2020

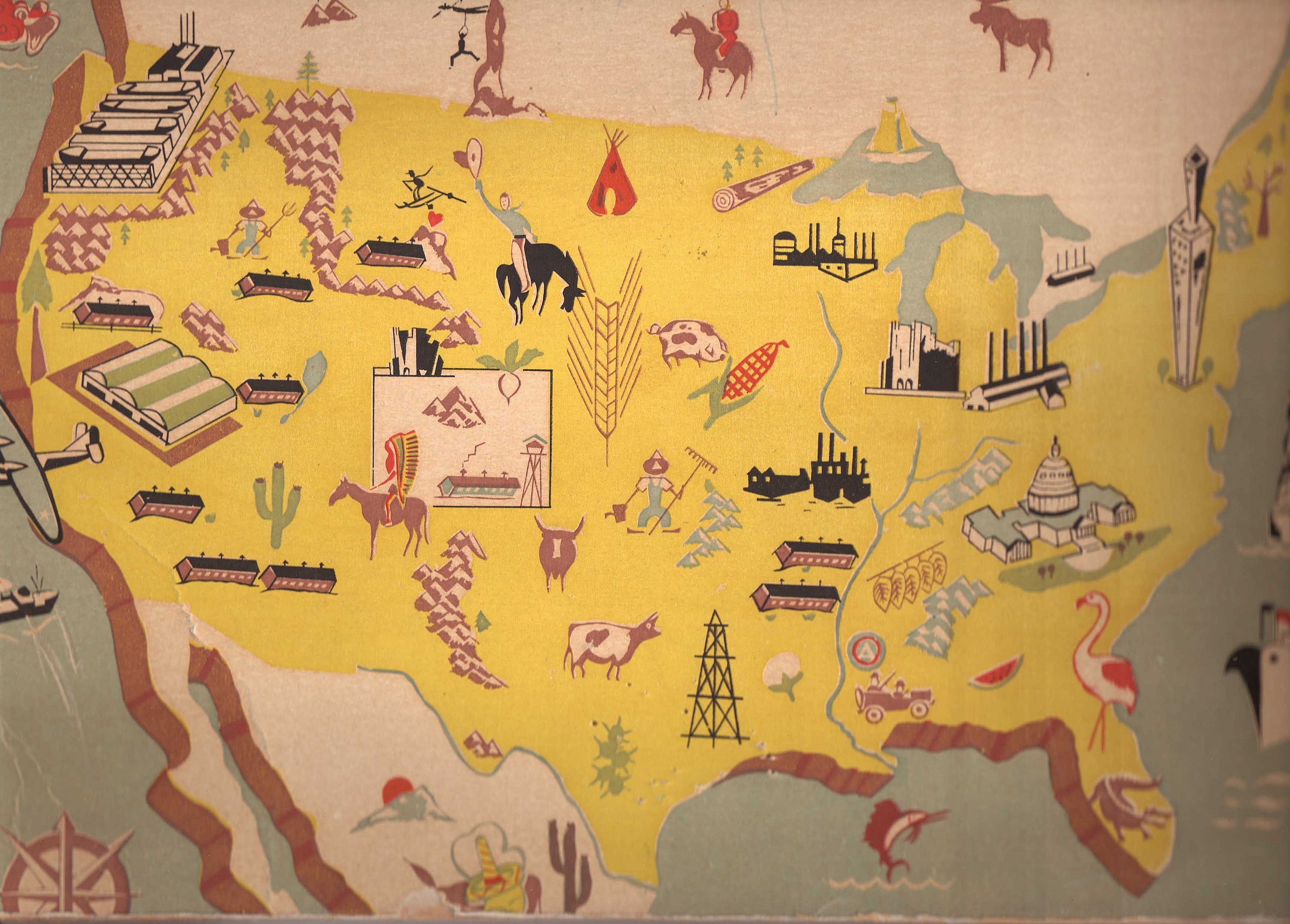

The Amache concentration camp in southeastern Colorado was, in many ways, similar to other War Relocation Authority camps where Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II: rural and rugged, hastily constructed against the wishes of the surrounding community, prone to dust storms and harsh weather. But one thing that was unique to Amache was its successful silk screen shop, run almost entirely by Japanese American incarcerees.

Amache (also called Granada, after the small town about a mile outside the camp) held a peak population of just over 7,300 Japanese Americans, mostly from different parts of California — though because of transfers from other camps, more than 10,000 people passed through in total. It was the smallest of the WRA concentration camps and the tenth largest city in Colorado at the time.

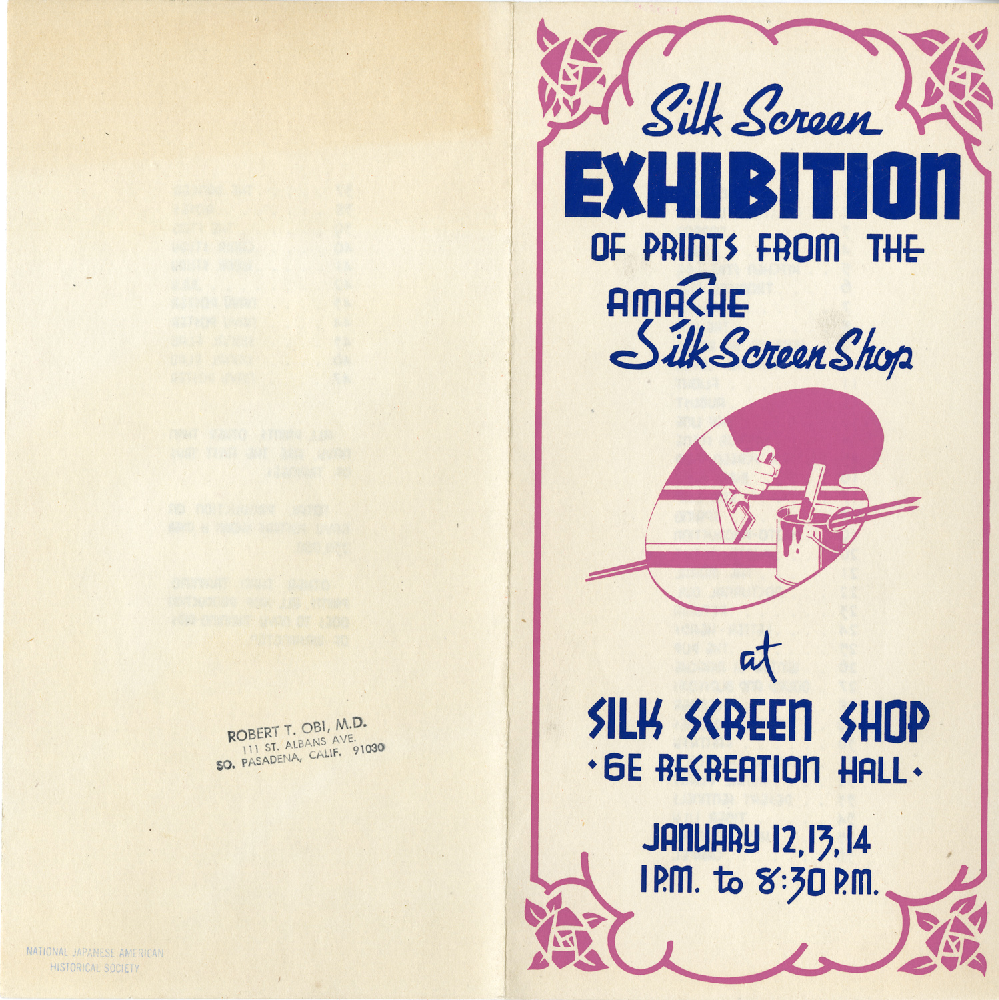

As in all the camps, Japanese Americans were encouraged (or, depending on your perspective, coerced) by WRA administrators to become productive workers patriotically supporting the camp operations and the larger war effort that had put them there. The Amache Silk Screen Shop — along with similar endeavors like the guayule project in Manzanar and several camouflage net factories — was initially created with this in mind. In the spring of 1943, as the war ramped up and created a labor shortage on the home front, a Red Cross nurse named Maida Campbell visited Amache to explore the possibility of running a printing operation there. Under her supervision, and at the request of the U.S. Navy, the shop officially began operations on May 31, 1943 with twenty-five employees, all Amache incarcerees.

Because the silk screen shop occupied a shared public space in a block recreation hall, production would sometimes be interrupted by haircuts, doctor’s appointments, and other meetings and amenities. But the biggest challenge was the constant, pervasive dust. The poorly constructed barracks offered little protection from the elements — for workers or wet posters — so the shop was often shut down by frequent sandstorms.

Within a few months of opening, the shop was producing tens of thousands of color posters for the U.S. Navy to aid with recruitment and training. But it wasn’t all propaganda. The Japanese Americans who worked in the silk screen shop also produced cards, magazines, calendars, commencement programs, high school dance bids, and other colorful materials for their fellow incarcerees.

Over its two-year run, the Amache Silk Screen Shop produced over 250,000 navy posters and countless prints, pamphlets, and other ephemera for the Japanese Americans confined in the camp. Many of these objects are still around today, saved by Amache survivors and their descendents as “positive mementos that reflect their ability to create a thriving, successful community despite the hardships and injustice of incarceration,” notes Dana Ogo Shew in her Densho Encyclopedia article on the silk screen shop. And thanks to the efforts of digital archivists — including our own hardworking collections team! — you can view some of these prints, and the people who made them, online.

—

[Header photo: Japanese American workers in the Amache Silk Screen Shop, c. 1943-1945. Courtesy of the George Ochikubo Collection.]