April 15, 2020

We’re fortunate today to have access to hundreds of testimonies from Nisei elders who were incarcerated as children during WWII. But the perspective captured in these oral histories is that of an adult looking back on decades-old memories, rather than a child or teen describing contemporaneous experiences. The journals and writing assignments they left behind, however — composed while they were students in concentration camp schools — offer a unique glimpse at how Japanese American youth thought and felt about their life behind barbed wire.

Minidoka teacher Helen Amerman tasked her Japanese American students with writing essays to describe their opinions and observations. Considering the audience and the restrictive setting in which they were written, some students might have been less than forthcoming. But even with these limitations, the writings help stitch together a compelling narrative about student life during WWII incarceration.

In their early essays, many of the students recall the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor and the climate of fear that soon engulfed their families and communities. Ninth grader Takako Mukaida wrote that, on the morning of December 8, 1941, “Something inside told me that I didn’t want to go [to school]. I tried to forget it, but I couldn’t. People on the streets were like policements, who watched every move I made. It made me feel like I was wondering through an unknown city.” [sic]

Mary Hara had a similar experience:

“The next day, Monday was a school day so I certainly dreaded to go to school. Even as I entered the bus, I felt a change as a few of the little boys began to snicker and whisper behind my back, but the older ones were much nicer and acted friendly. When I got to school, again I went through the same ordeal. Most of my friends were nice, but some were certainly not and showed it. These tried to make all the trouble for me as possible by spreading false rumors and such. Of course, they weren’t nothing but it still made me feel awful. I went through this routine every day until the Christmas and New Years vacation.”

For many of these students, the sudden surge in anti-Japanese sentiment, as well as the mass arrests of Issei community leaders in the days and weeks that followed, was an abrupt awakening to the adult realities of the world.

Amy Mitamura wrote, “Being the youngest in the family financial problems and such never bothered me any. But at the outbreak of the war when my father was interned and our funds at the bank were frozen, I realized for the first time that this was also my problem for I was part of it. Perhaps it was my first grown-up feeling of responsibility. This feeling grew as the year sped and finally we were evacuated.”

These journal entries also give a glimpse into what daily life in the “assembly centers” and WRA concentration camps was like for middle and high school students. The weather is a recurring character. As one student in Mrs. Amerman’s class succinctly put it, “This Idaho weather is enough to drive any Seattleite, Californian, Oregonian buggy.”

Hideo Morioka, writing in Tule Lake in April 1943, noted, “When we went to our classes the dust would rush against your face and body and most of all stuff your hair with sand. The dust was so thick sometimes it made it impossible to see in front of you when you are trying to go to your classes. I hope that is the last dust storm that we shall ever see for this month and on until winter.”

These day-to-day recordings are often rather dull — and the students themselves make frequent comments on the sheer boredom of camp life. But they also illustrate how quickly boredom could change to danger, like Aiko Kawaguchi’s account of the near drowning of a young girl in Minidoka (which preceded and perhaps foreshadowed the tragic drowning of two inmates in the same canal several months later, in the summer of 1943.)

“One incident I shall never forget is happened one day as we went down to the canal and were watching some girls swimming, when all of a sudden a girl yelled, but we all thought she was just joking. Later since she acted so true and yelled so long some men on the other side of the canal came and rescued her. She had drunk a lot of water and was hard to breathe. She and all the girls who went with her were so frightened they didn’t know what to do. If it had not been for those men she would of been at the bottom of the canal now. That is something to be real thankful for.”

Many of these essays and journal entries document efforts to improve their living conditions or create activities to fill the time. A series of “personality cards” written by high school students in Tule Lake describe movie nights, dance practices, a basketball league, a relay race up and down Castle Rock, and other social activities. Similar efforts popped up in other camps, and according to Mary Hara, who later ended up in Minidoka, there was even a circus with amateur trapeze performers in Portland Assembly Center.

Some students were a little more tongue-in-cheek, perhaps seeking to inject some humor into the dreary and depressing camp environment. A Hunt High student identified only as H.K. painted this unflattering portrait of a camp classroom: “Perspiring freely the young teacher at the map continued to explain the current topics. She was rather on the attractive side, but one would never guess it, by looking at the dead expressions on the faces of students sitting in front of her. The atmosphere reminded one of the morgue or even a dead man’s chambers.”

Meanwhile, Jack Murakami crafted what may be the world’s most poetic description of a supremely unpoetic odor that haunted camp residents: “As the silhouette of summer slowly desends [sic] upon Minidoka, the fragrant smell of garlic blooms and the sewage plant drifts about with the playful breezes. The sages around us hides secrets of nature and his subjects, busy at work. They too resent that fragrant smell.”

Others were more focused on the loss of their freedom, and the precarity of their future in a country willing to so easily discard their rights as citizens.

“I don’t like to be living out here in Idaho,” wrote Henry Fukuhara in Minidoka. “I don’t like it because there is not enough freedom out here as we used to have in our own States.”

In her “review of 1942,” Amy Mitamura expressed concerns about the future: “Today we are sheltered and fed by the government. What about tomorrow? Perhaps it’s better to worry about it when the time comes, but I don’t think so. What does 1943 hold for us?”

Tule Lake student Asako Ike echoed Amy’s fears:

“I was just thinking — what’s going to happen to us after the war is over. Either we’ll be sent overseas to Japan or perhaps there’ll be chance to stay here in the U.S. There’ll probably be depression…. With the depression and everything, and without any home to turn to I feel lost even now. Our family is quite large and with only a mother it’s going to be terribly hard on her.”

These fears were compounded by rumors swirling through the camps, as well as news from the outside that highlighted anti-Japanese sentiment. One student in Tule Lake described the often contradictory messages that appeared in news reports from home: “Reading the section of the Sacramento Bee ‘Letters to the People,’ a man wrote that he didn’t like to see any citizens of the United States in a camp. Then the other day my brother was reading to me about this man in San Francisco that if he saw a Japanese around there he’d kill him. Now there’s two opinions on the subject and two personalities.”

“Rumors are easy to spread here in this camp because it is crowded,” wrote Joe Abe, another Tule Lake student. “Some of these rumors may turn out to be true, but 99% have been false. But still one cannot blame these rumor-mongers but we here [sic] little of what the government is really doing…. When one put in a camp like this one they are ‘news-hungry.’ Anything they hear they pass it on.”

Even while facing these very real fears, students tried to remain hopeful and dreamed of life after camp. Some, like Masako Doi, wrote down wishes for simple, everyday pleasures like watching a movie in “a real theatre” or being “free to go out again.” Others, like William Hata, dreamed big:

“I dream often of being a man married with an important job in a big concern. A graduate of Oxford University with a Bachelor of Science, living in a big two story mansion with a spacious lawn and pool. The furnishings are nothing but the best, for instance take the carpets that line the floor, imported from Persia about four inches thick. We have a couple of kids make it John 7 and Mary 4, and boy do we have fun during the week ends, swimming and bashing in the sun in the afternoon and then a party inviting all my business friends with dancing in our well decorated ballroom. Well I think I had better end it here because my dream’s over.”

For many students, the underlying sentiment that comes across in their writings is a wish to, in the words of Lucy Fukui, “leave those painful memories behind and work for a brighter, happier future.” Despite the many losses and betrayals they had experienced, these Japanese American teens held onto their rights, and responsibilities, as citizens — even when their own country refused to recognize them as such.

“Let’s try to get as much education as we can,” wrote Mitzi Nagasaki, “and along with millions of other Americans, let’s help build up a better democratic country in which the future generation will live in peace and contentment.”

Of course, it’s safe to assume that some might have adopted a somewhat rosier view in an effort to appease their teachers — but even taken with a grain of salt, these student writings remain instructive today. Not only do they document an important chapter in our history, they also provide insight into how young people experienced that history and coped with the unfair consequences it created in their lives. As another generation weathers a very different crisis today, perhaps these youth voices from the past can help us all to adapt to the changes in our lives, find strength in ourselves and our communities, and dream of a “brighter, happier future.”

—

By Densho Communications Coordinator Nina Wallace

For more information see the Helen Amerman Collection and the Bigelow Collection, which contain student essays from Minidoka concentration camp. In the Helen Amerman Collection the essays are objects 93-182 and in the Bigelow Collection the essays are objects 46-94. UC Santa Barbara Robert Billigmeier Collection has “personality cards” that are described as essays by high school students in Tule Lake. The diaries of Takeharu Inouye, a student in Sacramento Assembly Center and Tule Lake concentration camp, are viewable in the Takeharu Inouye Collection.

See also the Densho Encyclopedia article on Ella Evanson, a middle school teacher in Seattle who corresponded with her students who were incarcerated. The letters were donated to the University of Washington and have been digitized.

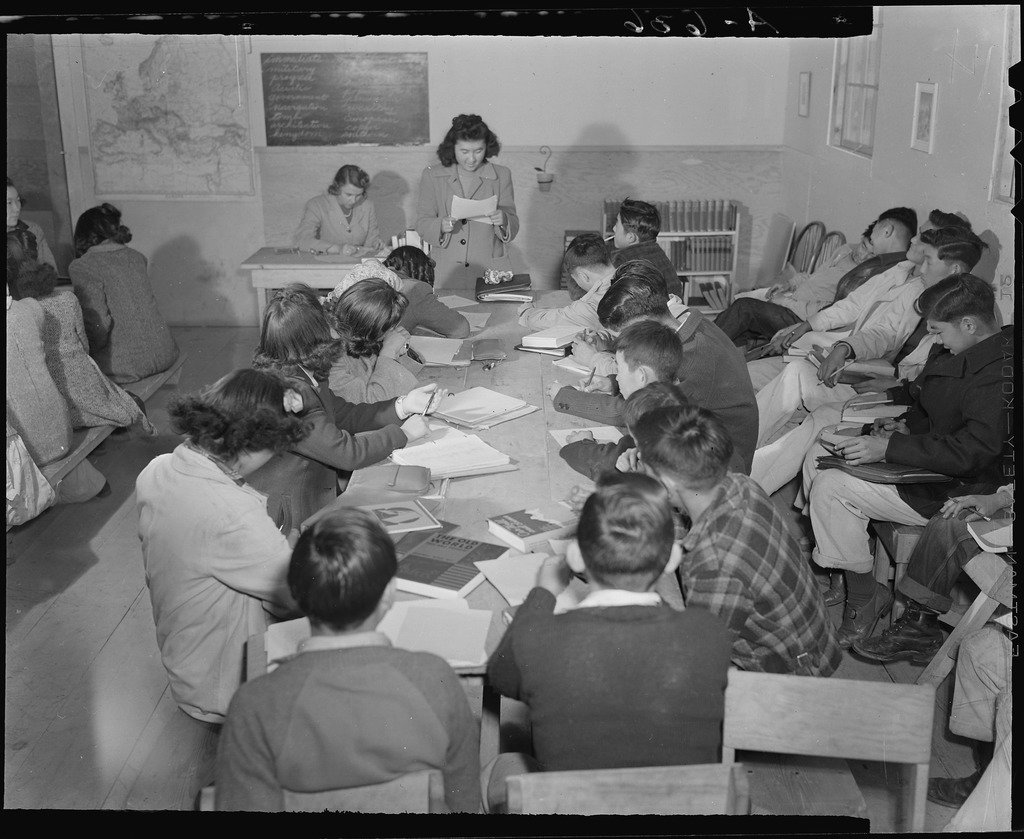

[Header image: Ninth grade classroom at Rohwer incarceration camp. Teacher is Mrs. M.H. Ziegler. November 24, 1942. Photo by Tom Parker, courtesy of the TOMO Foundation Collection, Sanoian Special Collections Library, California State University, Fresno.]