December 19, 2019

As one of Densho’s 2019 artists-in-residence, Mari Shibuya recently completed a mural that visualizes the histories of three Pacific Northwest Japanese American families. In this guest blog post, she reflects on her artistic process, what she learned about what it means to be Japanese American, and why this history remains so important today.

“Incarceration is the question you almost asked about the bruise you don’t remember getting.”

It lives in our bodies, in the stories of our ancestors and is laced into the backbone of America. The ‘Land of the free’ has the highest rates of incarceration in the world. Our prison industrial complex has expanded into an immigrant detention complex that disguises racism as political policy. ‘Never Again is Now’. As we look at the current state of immigration and detention in the United States there is a sobering call to examine the intergenerational impact of trauma and the role of the present in healing the past.

For my artist residency at Densho, I hosted three sessions of inter-generational dialogues where willing and interested nikkei of different generations could come together to explore the rippling impacts of the experience of Japanese American incarceration, and how this experience has sculpted the narrative of what it is to be Japanese American. To heal, we must reveal and hold the story of incarceration together.

There is a learning that gets unlocked by hearing the story of others who come from a similar ancestral experience, yet talking about it will only get you so far. To really dive into the story, we need the arts. Metaphor, symbolic expression and imagery allow us to reveal the nuanced, unconscious and unquestioned ways the experience lives in our bodies and in our family systems. Each session I hosted had an arts component, a storytelling component, and group discussion. Through arts based practices such as illustrating a model of our families’ stories of incarceration, collaborative poetry based on metaphors for incarceration and identity, storytelling trios, large and small group discussion, and sculpting miniature models of our lives, participants ranging from age 14 to 81 had the space to dialogue openly and honestly across the generational gap.

The space allowed folks to share family stories and get perspective on questions that we had not previously asked our family members — to share frustrations, questions about assimilation after the war, the experience of being biracial, and what parts of Japanese culture we identify with. The space to witness one another honestly reflect on their relationship to their families story and their journey in healing was deeply profound. For many folks who participated in the sessions this was the first time they had been in a space where there was such open discussion around incarceration. There was deep gratitude that this space was created and a thirst for more spaces like this.

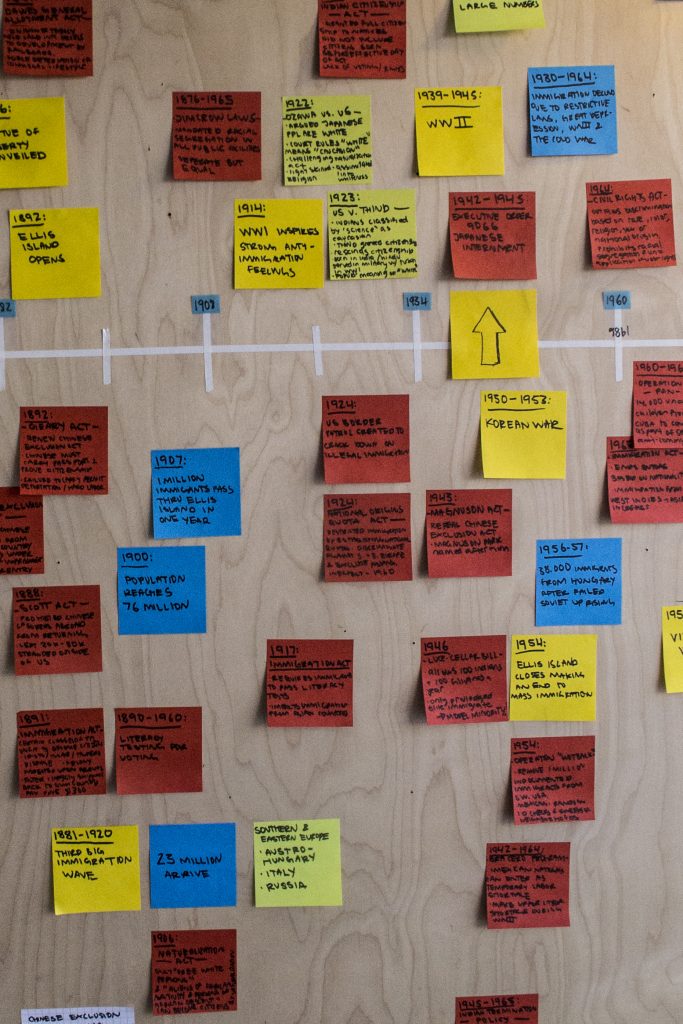

After hosting the dialogues, for my own personal journey, I made a solo pilgrimage to where part of my family was incarcerated in Manzanar. Struck by the power of the place and an urge to understand this event in the greater context of American history, I began research into the history of immigration in the United States. Upon returning home, I created a 12 foot timeline from 1492 to present day charting restrictions to citizenship, who was immigrating from where, and what historical events were transpiring during that time. What I saw was how policy shifts over time to target different immigrant groups and limit access to the resources and security that citizenship provides.

So, how does this relate to Japanese American Incarceration?

“Who did you become to survive?”

A common thread in the conversations at the dialogues was the strong tendency towards cultural assimilation post incarceration and how culturally ‘American’ values and the identity of being ‘American’ was propped up for the generation of children that followed incarceration. This is not to say that this generation did not identify as Japanese, it is to highlight that as a reaction to being imprisoned for your culture and heritage, it was strategic to assimilate. As the next generation comes of age (my generation in my family’s case), what I see is a cultural reclamation and deep thirst to hold the experience of incarceration and lift up of the strengths of our ancestors. There is a willingness to cry the tears of injustice that they did not, and to shine light on the resilience embodied in the term ‘Gaman’, as part of intergenerational healing.

To create the mural, I selected three families that participated in the dialogues and did in depth interviews with each family about their ancestry and their family’s story of incarceration. Based on these interviews, I created a visual map of their families story told through old family photographs and symbols, charting four fundamental areas: the immigration story, the incarceration story, cultural assimilation, and cultural reclamation. There is a red thread of fate connecting the events with the cultural facets of each person’s identity, weaving each family member into the unique expression of their ancestors that they are. There are also threads connecting individuals from different families to one another, symbolizing the power of affinity and shared experiences within generations and to remind us that we are not alone in our journey.

Through mapping each family’s story, I was struck by the parallels with my own family’s story and the similarity of the questions we have been asking ourselves. I thank all who participated, from the bottom of my heart, for sharing your story for this project and for contributing to a profound experience for me in doing this work.

The historic event of Japanese American Incarceration is just one of hundreds of incidents in the history of our country where policies have been put in place to drive a racist agenda and to limit the access of resources granted by citizenship and redistribute those resources to those who benefit from being a ‘citizen’ or from being viewed as ‘white’. This narrative continues on today. It is a shared responsibility that we all have as stewards of the present and conduits for life to grow through us, to be ambassadors for healing on this planet in the dire times we live in. ‘Never Again is Now.’ The ecological devastation mirrors the psychological devastation we have inherited as a species. To heal, we must love one another, love ourselves, support one another, and witness one another. Thank you for the opportunity to share a part of my healing journey with you all!

—

Guest post by Mari Shibuya, 2019 Densho Artist in Residence

Mari Shibuya is a hapa/yonsei artist, muralist and facilitator based out of Seattle. To see more of Mari’s work and find out more about them, visit www.marishibuya.com