February 7, 2018

Most of you reading this, I suspect, know a bit about the history of the so-called alien land laws. One of the most enduring tools anti-Japanese agitators used to target Japanese immigrants, their origins go back over one hundred years ago. As part of a drive to force Japanese immigrants out of California agriculture—except in the role as laborers—California passed the first alien land law in 1913. In order to pass muster with the Constitution, the framers of the law used the term “aliens ineligible for citizenship” to target Japanese and other Asian immigrants, since federal law prevented them from becoming naturalized citizens. This first land law prohibited aliens ineligible for citizenship from purchasing agricultural land and from long-term leasing. When Issei were able to get around the law through various loopholes—most notably by forming land corporations or purchasing the land in the name of citizen Nisei children—California passed a more stringent law in 1920 in an attempt to close the loopholes.

Not surprisingly, neighboring states sought to pass similar laws so that the hated Issei would not be tempted to move to those states, among them not just other western states such as Oregon, Arizona, and Idaho, but ones as far afield as Louisiana. While anti-Japanese sentiment mostly went dormant after the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924 banned all further Japanese immigration, it sprang back to life after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. As Japanese Americans on the West Coast were forcibly removed to American concentration camps, three of the states hosting these camps—Utah, Wyoming, and Arkansas—passed alien land laws to discourage any of the prisoners from settling in those states.

The effect of the laws has been debated by scholars. While the laws largely went unenforced, and the Japanese American presence in agriculture didn’t exactly shrink, the threat of the laws did certainly affect the type of crops Issei farmers chose and no doubt did influence many to leave the state or even the country.

During World War II, California began to aggressively enforce its alien land law as part of an effort to discourage removed Nikkei from returning. With the defendants incarcerated hundreds of miles away and their assets frozen, the state began filing escheat suits against Issei landowners, most of whom had purchased the land in the name of Nisei children. In a particularly hard-hearted move, the state targeted the Issei who had bought land in the name of Nisei who had subsequently been killed as American soldiers. Largely unable to defend themselves, most settled, paying a fee to quiet title and retain their land.

After the war, the alien land laws met their demise with startling rapidity. On the legal front a series of cases—Oyama v. California (1948), Fujii v. California (1952) and Masaoka v. California (1952)—invalidated aspects of the land laws and made them unenforceable. The Immigration Act of 1952 made Issei eligible for citizenship and the land laws at last obsolete.

Public sentiment towards Japanese Americans also changed after the war, and the land laws began to be repealed. The first indication of the changing times came with California’s Proposition 15 in 1946, which would have incorporated the state’s alien land law into the state constitution. Just a year after the closing of the concentration camps, California voters rejected Proposition 15 by a 60% to 40% margin. A decade later, California’s Proposition 13 in 1956 officially repealed the alien land law. Other states followed through the 1960s and beyond.

By the turn of the century, just three states still had alien land laws on the books. In 2002, Kansas finally repealed its law, followed by New Mexico in 2006. This leaves only Florida.

In 1926, Florida joined the tide of states adding alien land law legislation when it amended its constitution to add a provision establishing that “the Legislature shall have power to limit, regulate and prohibit ownership, inheritance, disposition, possession and enjoyment of real estate in the State of Florida by foreigners who are not eligible to become citizens of the United States.” Note that this language doesn’t actually prohibit land ownership, only giving the state the power to do so, making it different than the alien land laws passed in other states. But it nonetheless is in the spirit of those laws in its targeting of those “not eligible to become citizens” by federal law. Though this power has never been invoked, the law has stayed on the books to the present day.

In 2008, a ballot initiative to repeal the law in Florida failed; needing 60% of the vote to pass, it received less than 50%, as voters may have not understood the meaning of the phrase “aliens ineligible for citizenship” in a contemporary context.

Every twenty years, the Florida Constitution Revision Commission (CRC) meets to consider possible revisions to the constitution to put on the ballot. It so happens that 2017–18 is one of those years. At the urging of Asian American community leaders in Florida, the commission is considering a proposal to finally remove the last vestiges of the alien land laws. There will be a series of public hearings in 2018. Will this finally bring the era of the alien land laws to an end?

For more information on the CRC hearings this spring, see https://www.flcrc.gov/Meetings/PublicHearings; for more on current proposals to eliminate the law, see https://www.flcrc.gov/Proposals/Commissioner/2017/0003/ProposalText/c1/PDF and https://www.flcrc.gov/Proposals/Commissioner/2017/0003/Analyses/2017p0003.pre.dr.PDF.

—

By Densho Content Director Brian Niiya

We thank Luna Adachi of Miami for bringing this issue to our attention.

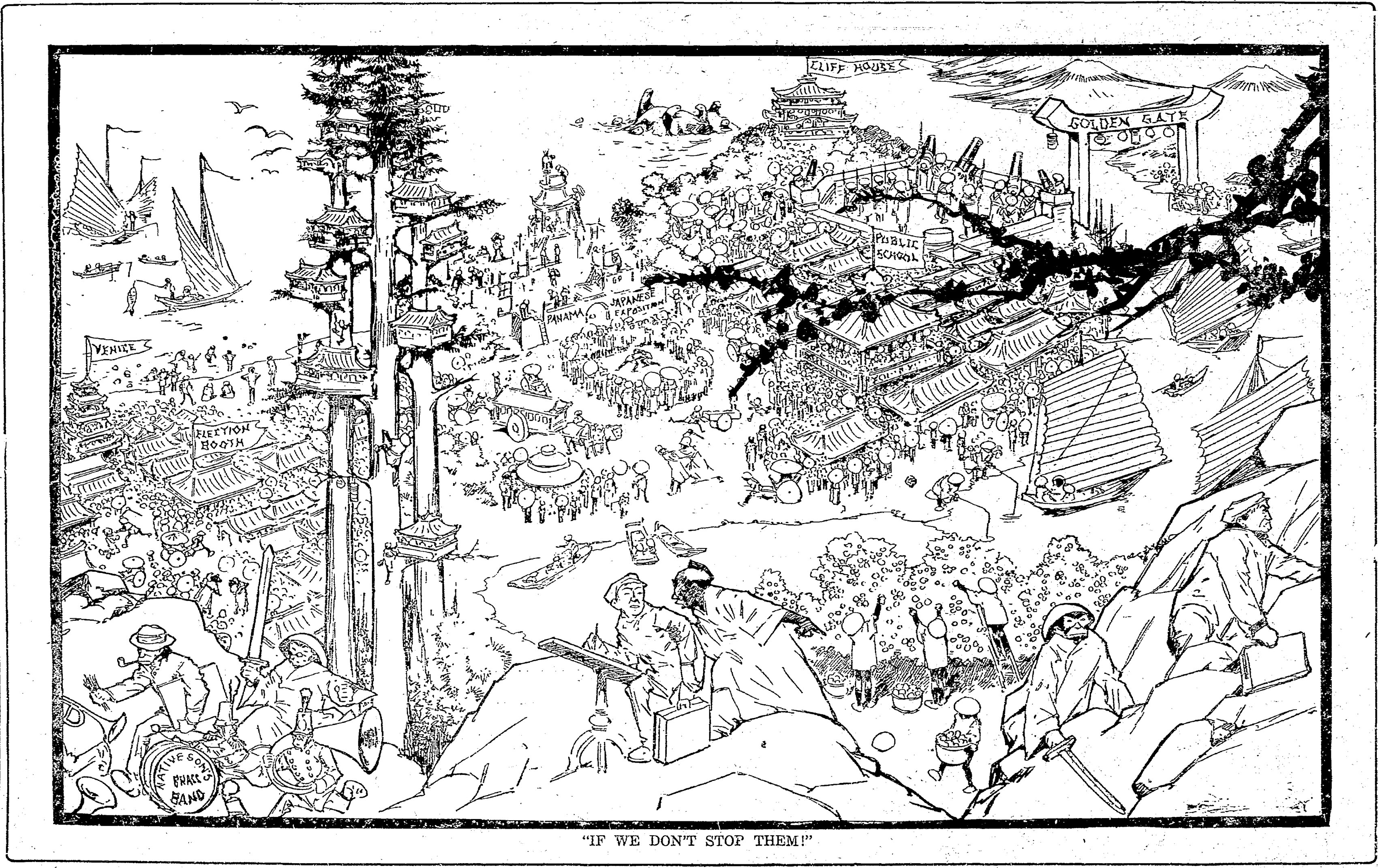

[Header photo: “If We Don’t Stop Them!” Anti-Japanese cartoon published in San Francisco, May 9, 1913. Courtesy of The Seattle Times Collection.]