August 22, 2016

“Nineteen forty-two, how full of events it has been. So many turning points, crisises [sic], days of anxiety and disappointment, yet some happy moments, too. It was like a goodbye to carefree days and a hello to reality.” Fifteen-year-old Amy Mitamura wrote these words in a school essay, “A Review of 1942,” during her fourth month of incarceration at Minidoka concentration camp.

Amy’s classmate Ikuko Ouje shared a similar sense of displacement, writing: “I lived for twelve years in one house. It had nineteen steps. Our neighbors moved and new ones came but we still lived on at the same old place until one day notice came that we had to move. That was the beginning of our moving days which never stopped until I came out here.“

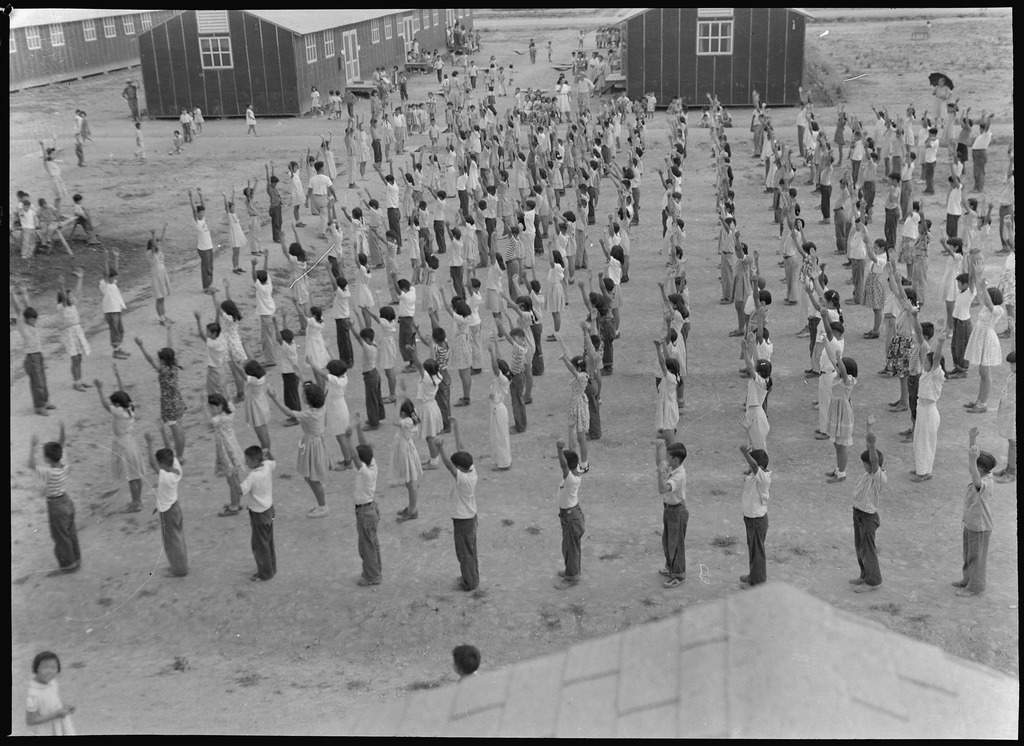

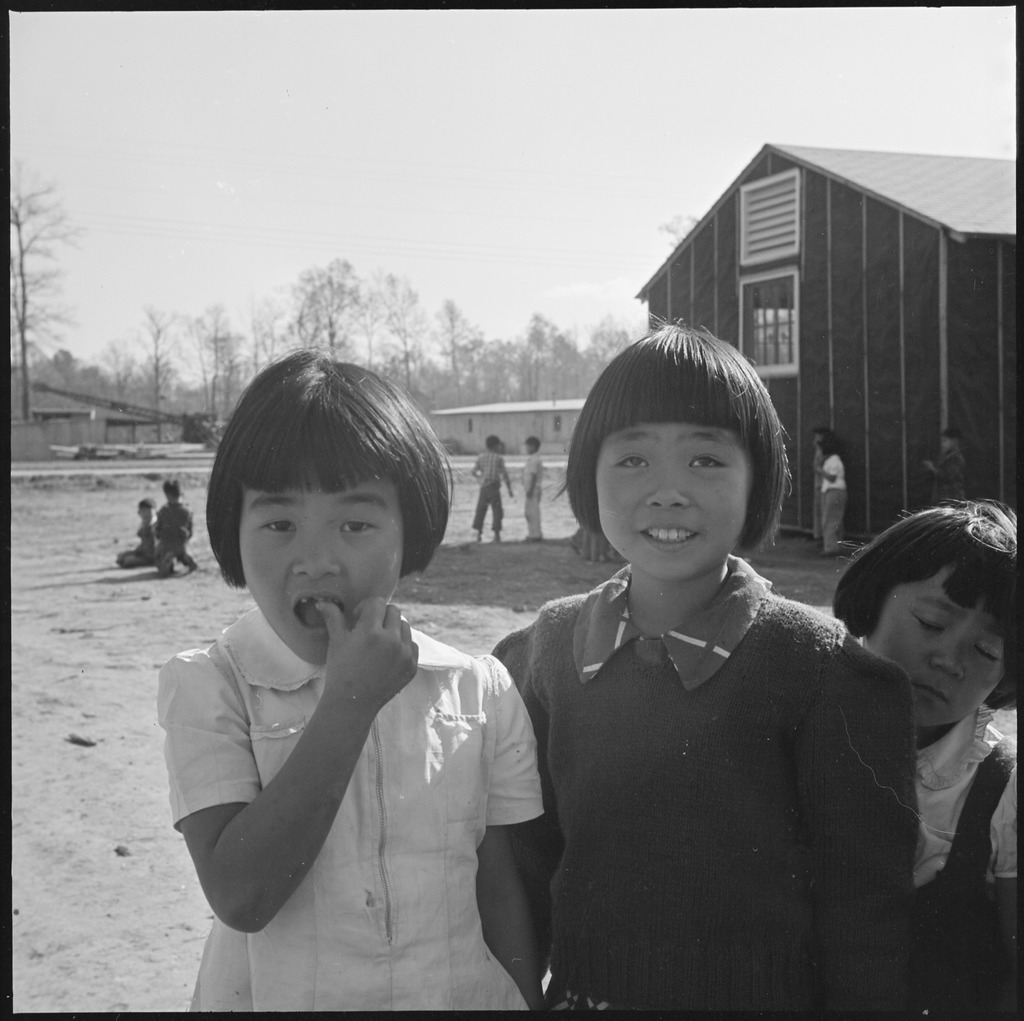

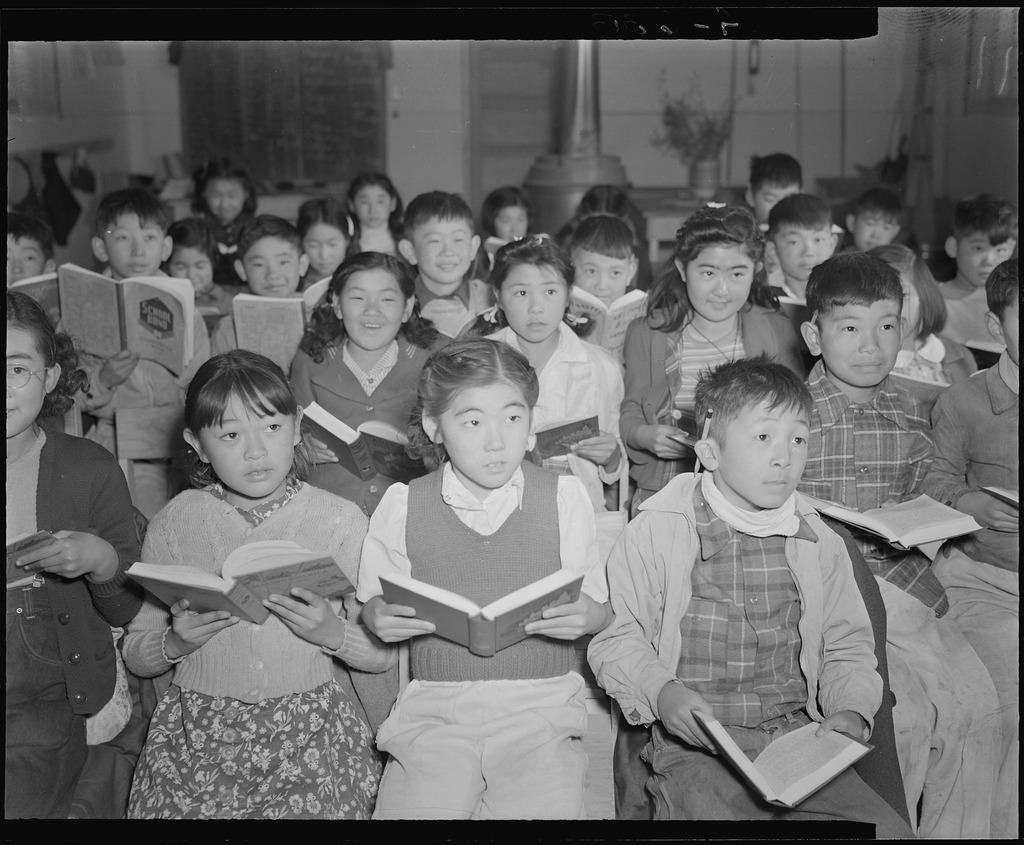

The events of 1942 would have been challenging by any standards: government-mandated curfew, the euphemistically named “evacuation,” and imprisonment at temporary facilities, then transfers to camps in remote, unfamiliar places. School-aged children experienced these traumas differently than their elders or younger siblings, and school–at least at first–didn’t do much to provide a sense of normalcy.

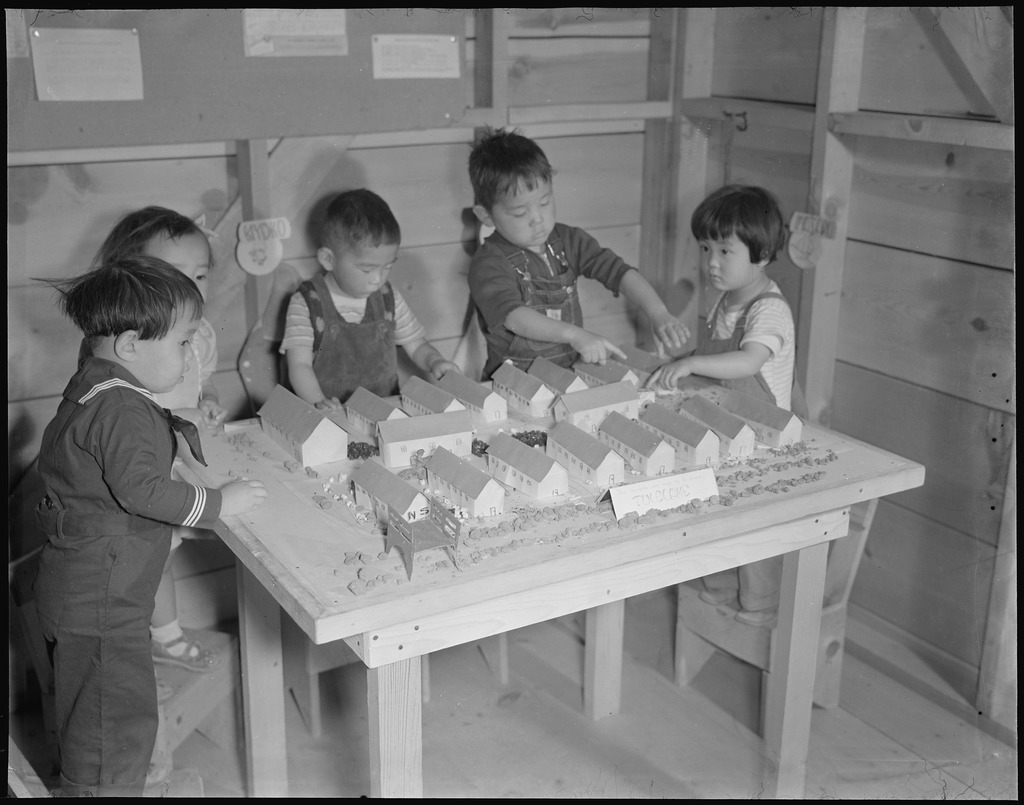

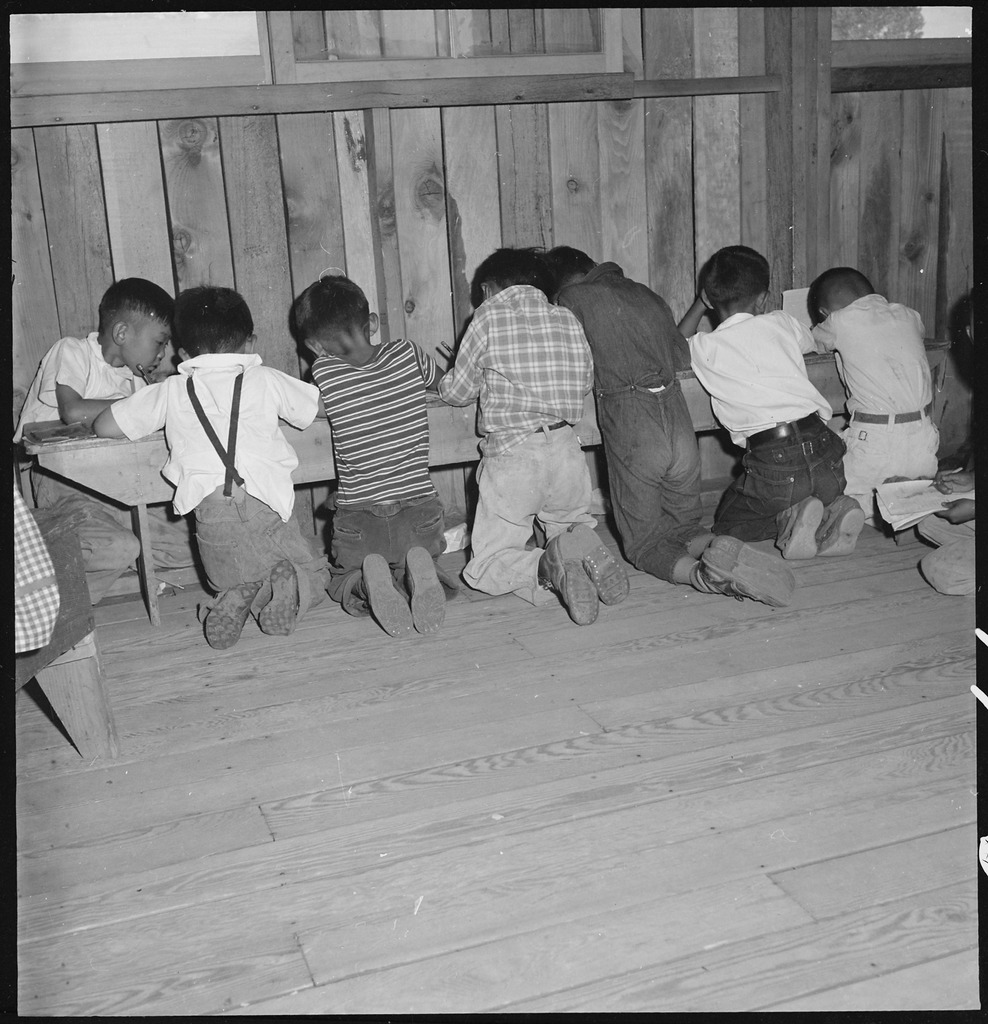

When incarcerees arrived at many of the camps, schools were still under construction. Temporary facilities were established in mess halls and unused barracks. Students sat on floors or on rustic, carved wooden benches. A lucky few had family members who made chairs that they were able to carry with them to school. These makeshift classrooms were often overcrowded. Clifford D. Carter, superintendent of Heart Mountain Schools, noted that classroom occupancy exceeded Wyoming standards by 80 to 100 percent, with one 20′ by 100′ barrack classroom reporting 203 students.

The sub-standard schooling and the limitations of camp life were not lost on children. As 14-year-old Henry Fukuhara astutely observed, “Well, this is my opinion why I don’t like to be living out here in Idaho. I don’t like it because there is not enough freedom out here as we used to have in our own States. This is not only my opinion, but many others that I know.”

Once schools were better established and provisioned, students reported both positive and negative experiences, a variety of which can be seen in Densho’s oral history archive. By the time the camps closed down in 1945, many of the schools had improved facilities and the same extra-curricular activities as schools on the other side of the barbed wire. But traditions like yearbook clubs and high school bands existed alongside overcrowded classrooms, “mandatory harvest vacations,” and a chronic lack of supplies.

Scroll through the photos below for a glimpse into what school would have been like for student incarcerees. Note that original War Relocation Authority (WRA) captions put a deliberately optimistic spin on the conditions of camp life.

—

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communications Manager

Sources (Research credit: Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director)

Horiuchi, Carol Lynne. “Dislocations and Relocations: The Built Environments of Japanese American Internment.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2005.

James, Thomas. Exile Within: The Schooling of Japanese Americans, 1942-1945. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987. Originally a Doctoral dissertation, Stanford University, 1984.

Nelson, Douglas W. Heart Mountain: The History of an American Concentration Camp. Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1976.