May 5, 2016

The case has ignited a debate as to whether Liang’s Asian American ethnicity is a privilege that ensured his innocence or a stigma that guaranteed his guilt. It is also a reminder of the enduring and pervasive “model minority” myth.

As we collectively wade through these charged debates, we offer a look back at the history of the “model minority.”Sociologist William Petersen is generally credited with coining the term in a 1966 New York Times article in which he compares Japanese Americans to “problem minorities” like “Negroes or Mexicans.” But the concept of the model minority — and its use to deny the existence of systemic racism — was already at play during World War II. War Relocation Authority (WRA) policy focused on separating “good” inmates who allowed the agency to maintain a sunny public image from “troublemakers” like the no-no boys and other resisters. Fearing they would grow dependent on government assistance the longer they remained in camp, the WRA prioritized resettlement for a select group.

WRA officials divided applicants into three tellingly racialized categories: “White” inmates were cleared for relocation, whereas “Brown” required further investigation and “Black” declared ineligible. Using information gathered from the controversial loyalty questionnaire, eligibility was based on assimilation: points were deducted for things like fluency in Japanese or practicing an “oriental religion.” Nisei deemed sufficiently Americanized were sent East with instructions to cut ties with their Japanese cultural roots and assimilate into white society as proof that the camps had, in the words of Director Dillon Myer, “provided new opportunities” for Japanese Americans.

Men serving in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team also figured heavily in WRA and JACL propaganda. A narrative of patriotic Nisei overcoming prejudice to join the ranks of “real” Americans allowed the U.S. to counter accusations of preaching democracy abroad while practicing racial exclusion at home. Ellen Wu explains in The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority, “the failure of the nation to live in accordance with its professed democratic ideals endangered the country’s aspirations to world leadership.” The rebranding of Japanese Americans as “assimilating Others… bolstered the framing of U.S. hegemony abroad as benevolent.”

Fast forward to the 1950s, when McCarthy fever was on the rise. Through propaganda and fear-mongering, unions and civil rights activists came to be seen as evidence that communism was taking root in America. Efforts to end restrictive covenants or address discriminatory hiring practices were cast as “socialist” and anti-free market. (Housing subsidies and other government programs aimed at expanding the white middle class, however, were considered positive achievements.) Soon, surveillance designed to root out “Reds” was being used to disrupt existing Black organizations and stifle emerging ones.

While Japanese and other Asian Americans were by no means immune from this, they were increasingly portrayed as a buffer between white and Black. As Yellow Peril fears began to ebb, African Americans demanding equal rights were targeted as the next great threat to white society. Removed from the spotlight, Asian Americans didn’t suffer the same disenfranchisement and abuse aimed at urban Black communities. Instead, Wu notes, they were seen as being the “ideal” minority: “at once a model citizen and definitively not-black.”

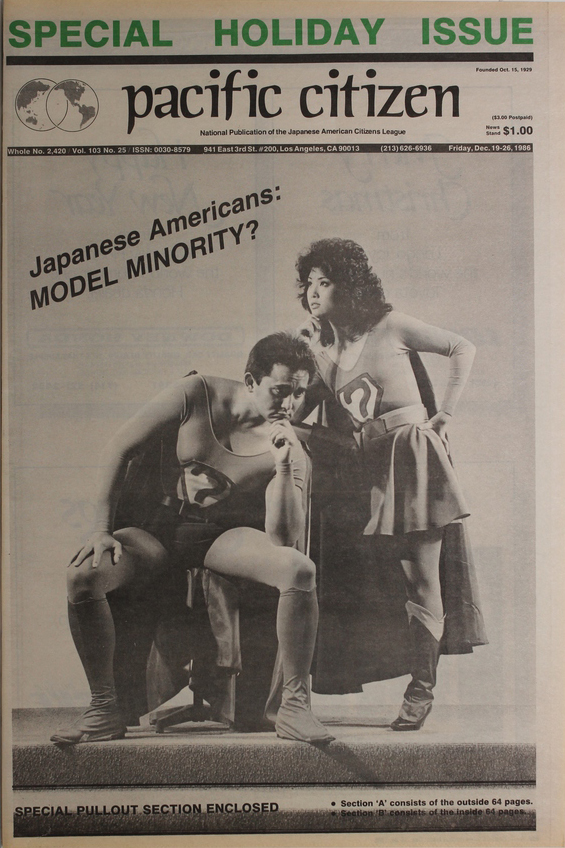

This model minority myth gained popularity as part of the backlash against advances of the Civil Rights Movement. Japanese and Chinese American entrepreneurship, low crime rates and high levels of education were held up as proof that people of color could succeed. The implication being that a lack of similar “success” in Black communities was the result of laziness and inherent criminality, rather than racist government policy. At the same time, the struggles of Pacific Islanders, Southeast Asians and other more vulnerable groups were largely erased as they were melded into the monolithic “Asian” demographic.

While some accepted this tacit agreement, many others pushed back — from Civil Rights Movement activists like Ina Sugihara and Grace Lee Boggs, to multi-ethnic coalitions of student activism like the Third World Liberation Front, to current movements to address state violence and immigrant rights.

These alliances between Black and Asian activists rarely make the news. Coverage of the Peter Liang case — following the example of the “race war” rhetoric surrounding the 1992 L.A. riots — has focused on fault lines between the two communities. What is often left out of the conversation is why (and to whose benefit) those divisions were created.

From its roots in Japanese American incarceration through its long history of criminalizing African Americans, the model minority myth has always served to marginalize voices of resistance. In fixating on whether Liang was denied the impunity given to his white counterparts, the question of why that impunity exists in the first place goes unasked.

Liang’s supporters see him as a scapegoat for white officers who avoided punishment for the same crime. The other side argues that Liang is guilty and his slap-on-the-wrist sentencing proof that he is part of a white supremacist system that uses violence to oppress Black communities. There is truth in both claims. That the rare conviction for killing an unarmed Black man was handed down to a non-white officer is not insignificant. Neither are the superficial benefits derived from “positive” stereotypes of a well-behaved minority. The Liang trial is an example of both the lie of the model minority and the legacy of anti-Black racism at the myth’s core.

—

By Nina Wallace, Densho Special Projects Coordinator