November 16, 2015

Alfred Alvarico, a participating student, understood that the work was more than a trash pick-up: “I feel that it was a great opportunity to come here and not just clean up but to respect the people in the 442nd and the people in the internment camp. I think it’s wrong to have people that are believed to be the enemy locked up even though they didn’t do anything to you.”

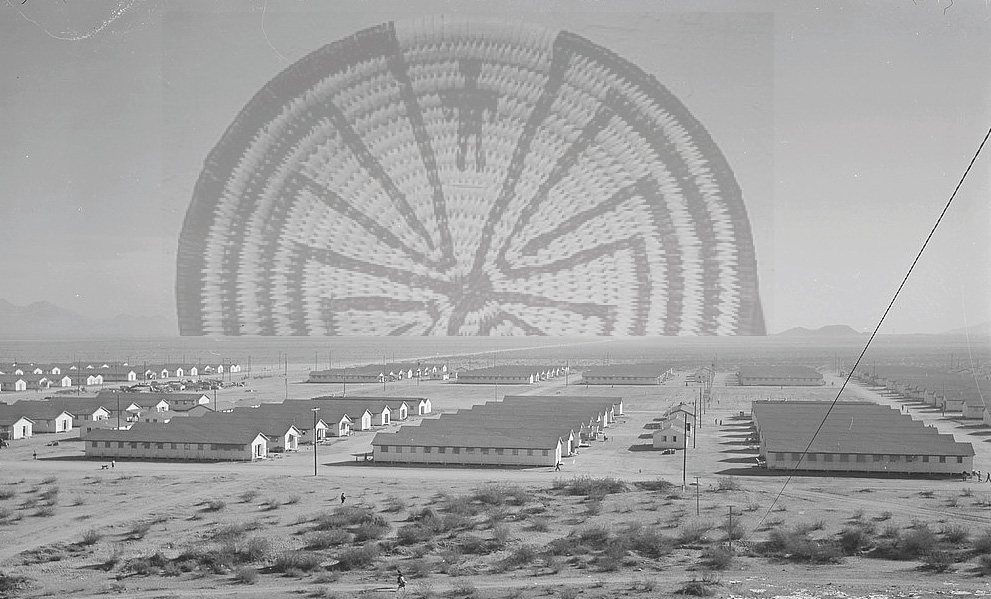

The story of Japanese American incarceration was, in fact, part of Alfred’s community’s history too. The monument, which was constructed in 1944 to commemorate the Japanese Americans who served in the 442nd is one of the few remaining structures from the Gila River concentration camp, which housed as many as 13,000 Japanese Americans between 1942 and 1945.

In this 2006 interview Arlene Johns, a member of the Akimel O’Otham tribe, recalled childhood encounters with those imprisoned in the camp:

“I [would] just go over there to the camps, see the little Japanese kids. They look at me, I look at them I moved the horse really close and we would just touch fingertips. [….] My parents and grandparents didn’t know that I was doing that [laughs] seeing the people over there. Later on when they used to come down and fish in the canals, I’d go over there and there was these three men who always came to fish, I went to the house and point to them, my grandmother and auntie they come with me and see that it’s them and they come across on the water and put me on their shoulder and I’d sit there under the willow and fish with them. They even made me my own fishing stick. So we caught carp and catfish so we did that all summer long, all the winter long.”

Arizona State University professor Karen Leong summarizes some of the intersecting Japanese American and Native American histories in her Densho Encyclopedia article about Gila River concentration camp:

In early March 1942, Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier wrote to the Secretary of War proposing that the Department of Interior be authorized to work with the Japanese Americans who would be removed from the western states as a result of Executive Order 9066. He noted that the Department had resources of land, welfare and recreational specialists, as well as experience working with an ethnic minority, the American Indians. Collier felt that Japanese Americans would be effective workers for reclamation and agricultural projects under the jurisdiction of the Department of Interior. The War Department ultimately selected the Gila River Indian Community and the Colorado River Indian Community, both reservations in Arizona, as sites for two of the ten concentration camps. Although Collier lobbied for the Office of Indian Affairs to administer both of these camps, partly because of the infrastructure that would be built at the War Department’s expense and because of the labor provided by the internees, the War Department only authorized Collier to have jurisdiction over the Poston Relocation Center at Colorado River.[1] The Bureau of Indian Affairs under Collier sought to limit the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to lands uncultivated, but the WRA, well aware of the need for the camps to cultivate their own food, took over acreage being cultivated for the tribe’s own agricultural pursuits.[2]

The Akimel O’otham and Maricopa Indians of the Gila River Indian Community, living on a reservation created and approved by Congress in 1859, formed an Indian Reorganization Act government in 1936. Nonetheless, the elected Tribal Council’s work was still subject to the oversight of the Office of Indian Affairs within the Department of the Interior. When the Council was notified in May 1942 that the WRA was going to lease 17,000 acres of its land for two camps, one by a canal and another by the Sacaton Butte, the members rejected the proposed agreement in favor of having the community vote. They once more rejected the agreement in September 1942, even though the camps were nearly complete. Only in October did the council narrowly vote to authorize the contract. Although some community members were hired to work in the camps as guards, as workers with the livestock, or in the war production factories, Gila River community members overall were not given priority for employment in constructing the camps or working within the camps.[3]

Upon closing, inmates left piles of makeshift furniture, dishes, and other items behind. The Gila River Indian Community members salvaged what they could from those items, but did not benefit from any of the major structures or infrastructure that had been constructed for the camp. Even the piping that provided running water and the wiring that provided electricity to the camps were removed, leaving the broken concrete foundations behind, even while the reservation lacked those same resources. The WRA refused to spend the funds it would cost to clean up these foundations, which rendered the land unviable for Gila River Indian Community use. The WRA also did not fulfill the terms of the contract with Gila River Indian Community because it did not cultivate the 8,500 acres of land as it had promised to do in lieu of rent.[19]

Since the closure of the camps, the Japanese American community in Phoenix has maintained positive relations with the Gila River Indian Community, primarily through the efforts of Mas Inoshita. The Gila River Indian Community verbally agreed to not build or utilize the former camp sites unless they absolutely had to, and this promise has been maintained to this day. In 1996, community members, scholars, and artists worked together to explore the experiences of Japanese Americans imprisoned in Arizona. Playwright Lane Nishikawa met with former inmates and developed a play, “Gila River,” that was performed by local community members at the Gila River Indian Community. Some of the Gila River Indian Community members shared their memories of the concentration camp, but a formal oral history project to preserve those memories did not commence until 2008.

Because the Gila River Indian Community maintains sovereignty over its land, which they privately own, visitors may not visit the former sites unless they have applied for and received a permit from the community and may be cited for trespassing; often this permission is only granted to individuals who can prove they are descended from former inmates.

—

Do you have stories about Native American involvement in WWII incarceration at Gila River or elsewhere? Let us know: info@densho.org

Read more about the Gila River concentration camp here; see photos of the camp at HistoryPin: