October 23, 2015

Book review by Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

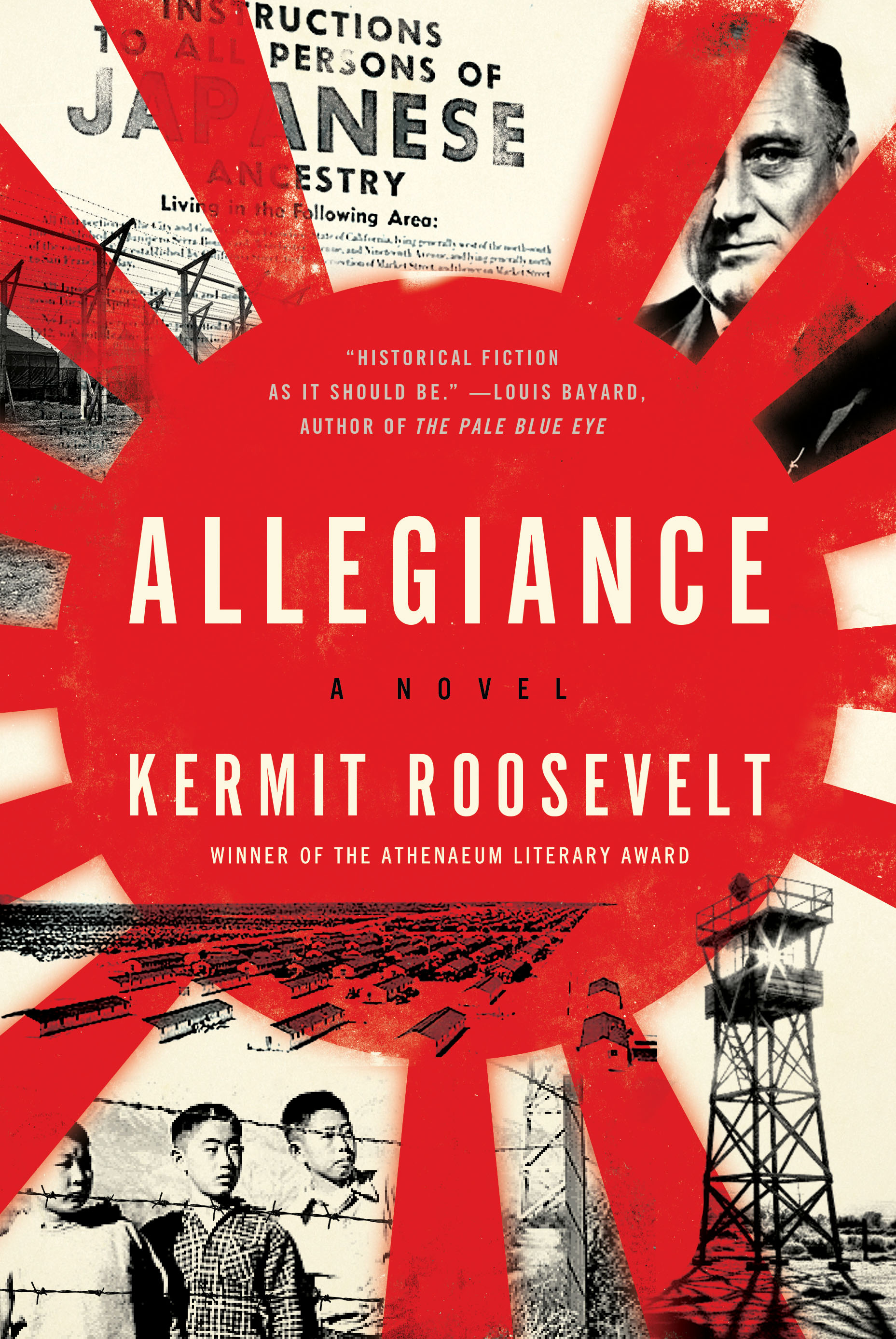

Kermit Roosevelt’s Allegiance is an engaging historical mystery novel set during World War II against the backdrop of the Supreme Court and the Japanese American cases. Its protagonist is Caswell “Cash” Harrison, a young Columbia Law School graduate when the war begins from a prominent Philadelphia family. After he mysteriously flunks his army physical, he receives a plum invitation to become a clerk to Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black. Though his girlfriend Suzanne, the daughter of a prominent local judge, doesn’t want him to go—and part of him wants to find a way to join the army to contribute to the war effort directly—it is too good an opportunity to give up.

At the Supreme Court, he finds nearly all his waking hours taken up with the review and evaluation of mountains of writs of certiorari, or “certs”; these are case summaries used to determine which of the many cases the court will hear. In between, he bonds with other clerks and builds his own relationship with his boss and other justices, particular Felix Frankfurter. But before long, some strange things start to happen: someone seems to following Cash, he is approached by the FBI about becoming an informant within the court, and, along with another clerk, he begins to suspect that some of the court’s decisions are not on the up and up. When that clerk is subsequently found dead in his office, Cash suspects murder.

After his one-year clerkship is up, he feels the need to remain in Washington to continue his investigation. He lands a job as a lawyer for the Justice Department, conveniently presided over by Francis Biddle, an old family friend from Philadelphia. While the murder/conspiracy plot deepens—and a halting romance with a new female clerk ensues—much of the book’s second act reads like a novelization of Peter Irons’ Justice at War. Cash replaces the departed James Rowe and plays the role of Rowe and John Burling in discovering the deliberate untruths in John DeWitt’s Final Report while being tasked to write the government’s brief in the Korematsu case despite this discovery. As in real life, he attempts to insert a footnote into the brief disavowing DeWitt’s report that is vetoed by Solicitor General Charles Fahy. In between, Cash is dispatched to Tule Lake, where he futilely tries to stem the tide of renunciations and where he becomes convinced of the injustice of the forced removal and incarceration.

Though the Japanese American cases are certainly central to the plotting, the book is really about Cash, a bright up-and-coming member of the establishment, learning about the darkness that goes to the highest levels of American business and government and that the very foundations of that establishment and the privileged life that he leads are built are a bed of corruption and dishonesty. The novel follows Cash’s attempt to reconcile these discoveries and to do the right thing, whatever that may be.

While the cloak and dagger stuff comes off a little forced, the narrative moves along at a rapid pace and keeps the reader turning the pages. It is heavily populated with real historical figures from the Supreme Court, Justice Department, War Department, FBI, and elsewhere. Many of these characters are vividly drawn. Black is shown as a courtly Southern tennis enthusiast with a penchant for burning steaks, while Frankfurter is portrayed as a Machiavellian schemer with immense influence on the court as a whole. Biddle is ineffectual and indecisive; Karl Bendetsen cruel and calculating. J. Edgar Hoover and his top aide Clyde Tolson are by turns menacing and vaguely comical. All seem to conform fairly well to what is known of them.

The author—a legal scholar at the University of Pennsylvania Law School—has done his homework and the history as portrayed in Allegiance is mostly accurate. Inevitably, there is some time shifting of events to make various plot elements work.

For instance, Cash and Justice Department colleagues receive DeWitt’s Final Report after the Tule Lake draft resistance cases in the summer of 1944; the report was actually released some six months earlier. It is claimed that Tule Lake inmates renounce their citizenships out of fear of what’s happening to those who have left camp; “In California, shadowy figures shoot through windows and mobs burn houses.” But this is in November of 1944 in the book; while such terroristic activity does indeed take place in California it doesn’t happen until after the restrictions to returning to the West Coast are lifted starting in January 1945.

But there are two larger historical issues that might irk some readers. One is in the treatment of the Tule Lake draft resistance cases. This is a key point in the plot, since it is where Cash learns about the treatment of inmates in the concentration camps and comes to see it for the injustice it was. His education comes largely in the form of a trial for lead defendant Masaaki Kuwabara and his 26 fellow defendants that allows them to tell their stories to the court—and to Cash and the reader. Judge Louis Goodman finds for the defendants and sends them sent back to Tule Lake. But the specifics of the trial are entirely made up. While Goodman did rule in favor of the defendants in real life, he did so by dismissing the charges entirely. The plaintive testimony of Kuwabara and his fellow defendants is an invention. There is no explanation of this in the author’s note.

The second is what seems to be intended as Cash’s redemption: in the end, he takes up the cases of the Tule Lake renunciants and prevents their deportation. Of course these actions were in real life performed by the legendary attorney Wayne Collins. Though the author does point this out in the author’s note, some may find it distasteful for Collins to be written out of the story and his heroic actions attributed to a government lawyer. It seems that Collins could just as easily have been written into the story (one wonders what the author would have done with a fictionalized version of a character as colorful as Collins), with Cash somehow aiding his efforts. This plot twist also adds to the Forest Gump-like effect of a single figure somehow managing to influence history from so different places, something that stretches credulity.

The main flaw of the novel, however, is the brief and frankly insufficient author’s note. In addition to the omissions noted above, the four-page note does not for the most part list any sources or provide the reader with any recommended readings for learning more about the many historical episodes detailed in the novel. This seems like a missed opportunity. Though he does mention Irons’ Justice at War and a couple of other important works, he doesn’t mention many others, including Eric Muller’s Free to Die for Their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), from which he cribbed much of the description of the Tule Lake draft resistance trial (at least the part he didn’t invent). The note also claims that, while many historical figures appear in the book, that “the characters around whom the conspiracy plot of this novel revolves… are my inventions.” Among these is John Hall, a War Department lawyer who is a fairly major character in the book. Yet there was an actual War Department lawyer with the same name and who held a similar position and performed similar actions as the supposedly made up character. Is this supposed to be a different person than the historical figure? An explanation of this would have been helpful.

Historical issues aside, this is still a fun and informative novel that takes us through a dark period in history in a mostly accurate and very lively manner. It is a shame that more information about that history and the liberties that author took with it isn’t provided within the covers of this otherwise enjoyable read.