October 13, 2015

Book review by Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

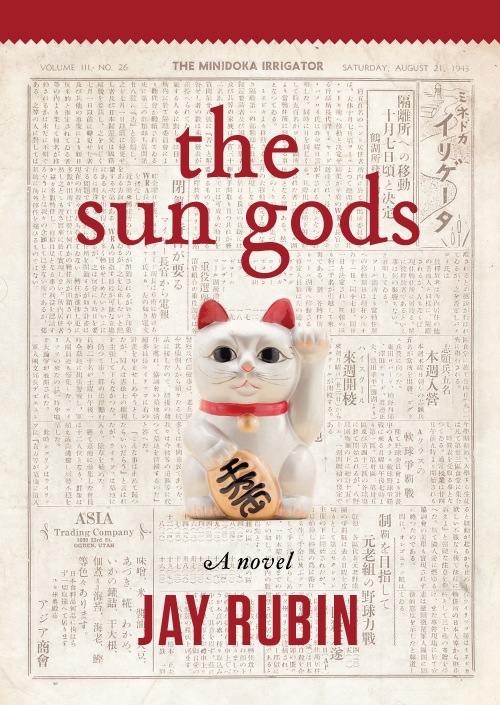

Set largely in Seattle, Japanese literary scholar and translator Jay Rubin’s The Sun Gods tells two separate linked narratives, one taking place just before and during World War II and the other twenty years later. In the late 1930s, Reverend Thomas Morton is a young widower with a toddler son and an enthusiastic English language pastor of a Japanese Christian church when he is swept off his feet by Mitsuko, the newly arrived sister of a regular member of the congregation. Mitsuko forms an instant and mutual bond with Morton’s son, Billy, and he hires her as a babysitter. She soon moves into his home, and love and marriage inevitably ensue. But Morton soon finds himself drawn into the ominous reports of Japanese military aggression in Asia and begins to absorb the anti-Japanese sentiment permeating the larger American society, straining the marriage. By the time his congregation is to forcibly removed and sent to American concentration camps, Morton has largely abandoned Mitsuko and Billy, who refuses to leave his stepmother’s side. The other story picks up with an adult Billy attending a religious college in the late 1950s and finding himself oddly drawn to Japanese culture, despite his father’s harsh renunciation of all things Japanese. A strange Nisei man who seems to know him begin to open the doors to his mysterious past.

I find myself with mixed feelings about this book. In reading it, I alternated between thinking it awful (much of the first quarter of the book) and then thinking it was not too bad, then really starting to enjoy it, then being kind of disappointed again. What didn’t I like about the first part of the book? I think I found the portrayal of Issei to be entirely unconvincing, for one thing. Because they lived in a Japanese language world, it is very difficult to portray them in an English language work, and this one is no exception. As is the case in many fictional works, the Issei here seem to exist in an Issei/Nisei netherworld where they seem to read only English language newspapers and conveniently speak English well. There is also too much exposition. Characters explain historical facts in a way that might be enlightening to some readers, but that sounds phony as actual dialogue.

When one character returns to his family after having been interned in Montana, for instance, he succinctly explains what happened to him in a manner that would make a contemporary history professor proud, including things that he would not likely have known at the time. There are also many clichéd scenes of discrimination and hardship faced by the Japanese Americans. In another scene that I found unintentionally humorous, a woman on the verge of forced removal breaks valuable dishes rather than sell them to a woman offering a fraction of their value. But perhaps to distinguish itself from the many other works depicting similar scenes, the woman breaks statuary and many dozens of dishes, collapsing an entire table of dishes with unbridled fury.

Reading dramatic works such as this, one wonders if any dishes were ever sold or if all in fact had been broken. At least we don’t get the pitiful pet that had to be forcibly left behind. But what I think I liked least about the novel is its valorization of physical beauty. Whenever a new character is described as physically attractive, the reader immediately knows that (a) this will be a major character and (b) that character will be getting it on with someone shortly. The physical descriptions—”stunning” women with “full lips and the double-fold eyelids” and “tall and well-built” men—all too accurately foreshadow their fate in the story as well the characters’ non-physical attributes.

But with the move to concentration camps, things shift a bit. The scenes in Puyallup and Minidoka are well presented and largely stick to known historical facts. (The author does invent two shootings by guards at Minidoka, however.) The novel really comes alive when the grown up Bill heads to Japan to study the language and culture in the early 1960s. Both urban Tokyo and rural backwaters are lovingly described in detail (without knowing for certain, these sections read as if autobiographical), and the plot takes some unexpected twists that had me turning the pages quickly to find out what was going to happen. One of the book’s central themes is religion, and for the most part, the author handles this well. Several characters wrestle with religious faith and its meaning in the midst of war that brings us genocide and nuclear holocaust. Grown up Billy’s growing doubts about following in his father’s footsteps are reinforced by his journey to Japan, where he discovers a spirituality divorced from organized religion per se. Unfortunately, his father fares less well, and his portrayal as a religious zealot comes off as cartoonish, his sudden heel turn too abrupt and unbelievable.

The Japanese Christian characters also find their faith complicated by the war and the racial and imperial baggage attached to their religion. So should you read this? The book this reminds of greatly is the hugely popular The Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet by Jamie Ford. Also set in Seattle, also jumping back and forth between the war years and the later present of the novel, also largely about characters in the present searching for lost loved ones from the war years, and also by turns cloying, manipulative, and affecting, I think your reaction to that book—which I have similar mixed feelings about—will be very similar to your reaction to this one. So if you liked Bitter and Sweet, go get this one. If that one didn’t work for you, this one probably won’t either.