October 2, 2015

Densho’s Content Director, Brian Niiya, adds: “On the one hand, it is true that many programs were successful in the sense that they grew a substantial portion of vegetables (and meat, in the form of livestock) consumed in the camps, and in some cases—most notably Gila River—grew crops for other camps and even crops such as flax and cotton to aid the war effort. On the other hand, there was a good deal of opposition to the the agricultural programs from a number of directions. Some inmates felt that, as prisoners, they should not be compelled to grow their own food. Some objected to the cynical motivation of the WRA/BIA with regards to viewing the inmates’ expertise and labor as vehicle to prepare local lands for future agricultural use; this was particularly true of the BIA run program at Poston, but a motivation at other camps as well. There were labor shortages at many camps due to the hard work and low pay as well as the fact that inmates could receive prevailing wages for farm labor on the outside (many inmates did such work on short term leave in 1942 and 1943). There were also strikes of agricultural workers at several of the camps over equipment, working conditions, food (insufficient diets provided for the rigorous work required), and other factors. The all hands-on-deck nature of some of the ‘fall harvest’ pictures reflects these factors; the closing of schools for harvest was in part a strike breaking measure.”

In a recent Agricultural History article, Karl Lillquist shed more light on the strife surrounding the agricultural programs: “Internal problems also affected labor. Strikes associated with a variety of work and living conditions impacted Heart Mountain, Manzanar, Minidoka, Topaz, and Tule Lake agricultural programs. Heart Mountain farm workers went on strike after their requests for better farm equipment were rejected by Caucasian farm administrators Administrators responded by bringing in ‘strike breakers’ from the center’s high school […] Tule Lake had to bring in evacuees from other centers to complete the 1943 harvest during a major strike. Interestingly, the evacuees brought in were paid prevailing ‘outside’ wages of $1.00–$1.45/hour rather than standard relocation center wages. Students and volunteers helped save agricultural programs in each of the centers during strikes as well as at other times of labor shortages. Heart Mountain and Tule Lake even had ‘harvest vacations’ from school.”*

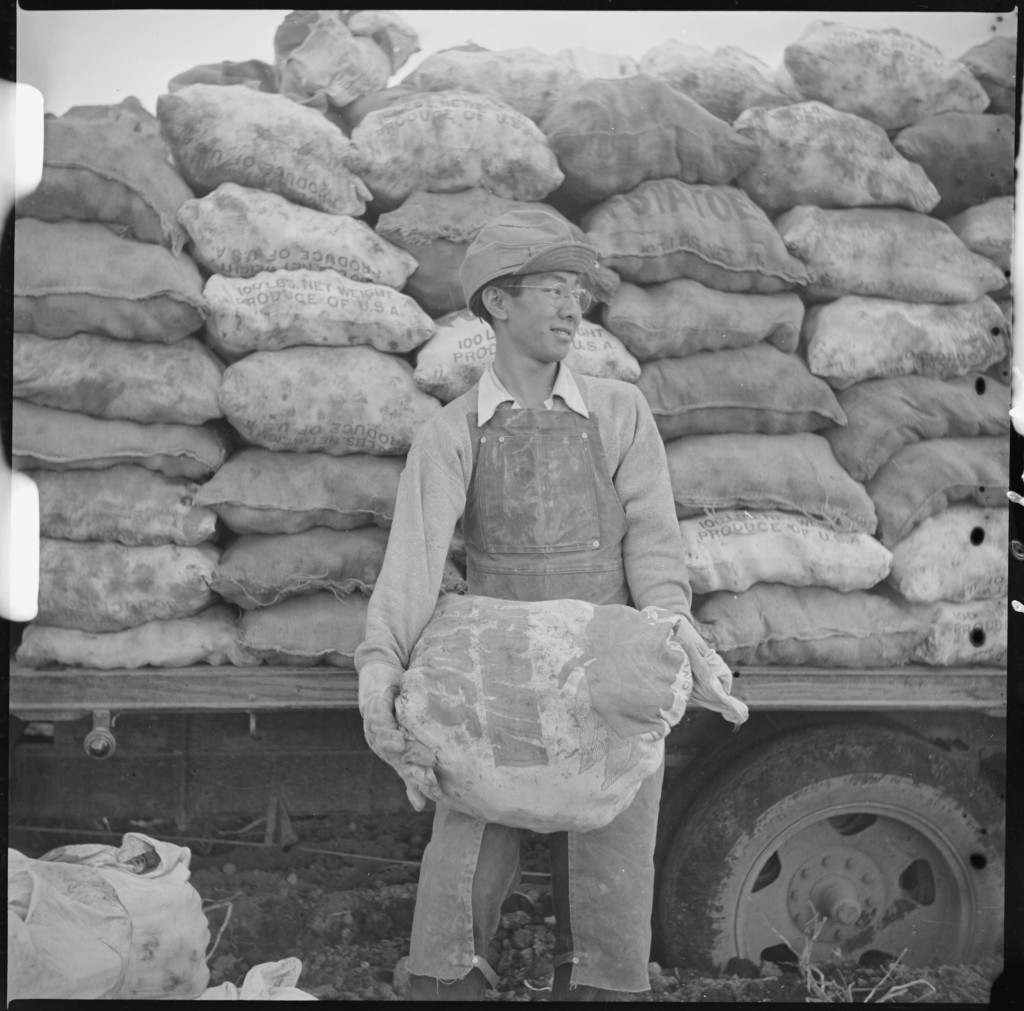

The WRA photos and captions below attempt to put a sunny spin on what was, essentially, forced labor. As you browse through the images, take note of the various ways the WRA might have used the photos and their captions to lend a false sense of harmony and accord to the fall harvest in their WWII concentration camps.

—

*Lillquist, Karl. “Farming the Desert: Agriculture in the World War II-Era Japanese-American Relocation Centers.” Agricultural History 84.1 (Winter 2010): 74-104.

—

Natasha Varner, Densho Communications Manager