May 20, 2014

Many years ago, when I worked at the Japanese American National Museum (JANM), in the early to mid 1990s, one of the most popular attractions in the old “Legacy Center” of the historic building—before the construction of the new building—was a computer file we colloquially referred to as the “camp database.” For a small donation one could look up and print out “camp records” that indicated what camp a given person or family had been in, along with a host of other information including prewar location, occupations, age, schooling, and so forth. In those largely pre- (or at least limited) Internet days, it seemed kind of miraculous. For many visitors, it must have felt like a validation that yes, this did happen, and here are the government records that prove it. Though perhaps seeming less miraculous to our jaded post-internet eyes, this database—officially titled “Records about Japanese Americans Relocated during World War II—is available online through the National Archives and is still a useful tool for various kinds of research.

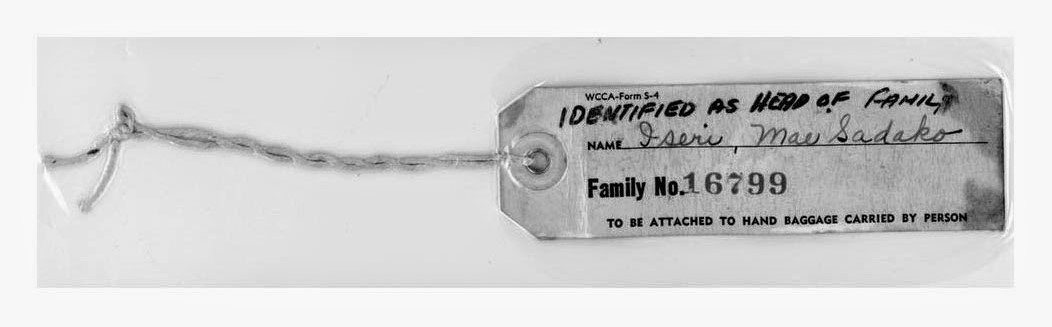

The story of these records is itself an interesting one. The data for them comes from Form WRA-26, a census type form that was completed for all inmates in the War Relocation Authority (WRA) concentration camps in 1942–43. Completed by inmate interviewers by April of 1943, the WRA transferred the data to punch cards, largely using inmate labor at Topaz, where they established a statistical laboratory in Block 2, Barracks 9 in November 1943. For about a year, up to fifty inmates compiled data under the supervision of WRA statistician Evelyn Rose. Once transferred, the WRA used the data to prepare a master file of inmates and for tables of demographic information included in its 1946 report, The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Description. (This WRA report, along with the many others, is also available online and will be the topic of a later post.)

After the war, the records of the WRA went to both the National Archives and to the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley; copies of the Form 26 punch cards went to both places. In the 1960s, Bancroft Library staff migrated the data from the punch cards to magnetic tape. Two decades later, the movement for redress and reparations culminated with the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 and the formation of the Office of Redress Administration (ORA) to administer the reparations process. Finding out about the Form 26 tapes, the ORA acquired a copy from the Bancroft and used it as a tool to identify and verify reparations recipients. JANM was also able to acquire a copy. Then in 2003, as part of its Access to Archival Databases project, the National Archives and Records Administration made the records available online. You can access the database here.

Though certain fields have been blocked from the online database for privacy reasons, the database can be very useful for researchers. It is a good source for genealogical type information for individuals or families. One can find out what camp—both “assembly center” and WRA camp—an individual was in along with her family number, which allows for the identification of other members of her family unit. One can also use the data to do research on groups of inmates—viewing records of all of the artists in Topaz for instance, or which inmates from the Pacific Northwest went to a camp other than Minidoka.

There are also limitations to the data. The major one is that the data comes from when inmates entered the camp, so information on where inmates went to after leaving camp is not included. (There is another set of WRA information—the Final Accountability Records (FAR)—that does include this information. This information is mostly not online, though the Topaz Museum offers the FAR information for Topaz only. Densho is planning to digitize the FAR for all of the camps.) There are inevitably spelling and other sorts of errors in the records, but not as many as one might think there would be, perhaps due to the fact that much of the work in both gathering and transferring the data was done by Japanese Americans.

There are some 110,000 individual records in the database. Beyond any specific type of research, just scanning through just a small portion of them—just the Takahashis, for instance, a list of 614 names—gives one a sense of the scope of what took place, the enormity of the civil and human rights violated in 1942. It is this sense a sobering resource—and one you no longer have to go to Washington DC or Los Angeles to visit.