April 22, 2015

Excerpted from the Densho Encyclopedia entry, Arts and Crafts in Camp

By Jane E. Dusselier, Iowa State University

In their efforts to create physical comfort, detainees laid the groundwork for remaking mental and physical landscapes of survival by using art to decorate their living quarters. Stripped of their personal possessions, detainees demonstrated their commitment to survival by inhabiting their living units with art in the form of kobu, wood-carvings, ikebana, embroidered wall hangings, and paper flowers. Camp-made crafts articulated fluid, shifting, and multiple stances against oppressive living conditions. By filling their living units with art, detainees made their surroundings look and feel less like spaces of incarceration, an important consideration for parents who struggled to establish even limited amounts of normalcy for their children. Through and with art, detainees spoke loudly voicing commitments to survival by improving their material lots in life and remaking both physical and mental landscapes. In this way art aided detainees in developing understandings of themselves as agents of their own lives. By remaking inside places of imprisonment, detainees identified with each other on the basis of survival and comfort.

Artificial flowers were one popular way to make living quarters more hospitable. Careful to save colorful pages from catalogs and magazines, women transformed the paper into flowers and then sewed them onto muslin covered balls stuffed with wadded paper, sewing scraps, or discarded bedding materials. Measuring approximately six inches in diameter, these artificial flower rrangements were hung from ceilings and walls of living units. Other women created similarly flowered art forms from silk scraps.[19] Women imprisoned at Poston made artificial crysanthemums, gardenias, irises, sweetpeas, cherry blossoms, lilacs, and carnations from colored paper that once lined apple and orange crates. Miwako Oano described her friend’s flowers as “so beautiful and so realistic that when I come home every day, my first impulse is to inhale the sweet fragrance one would expect to find emanating from such loveliness.”[20]

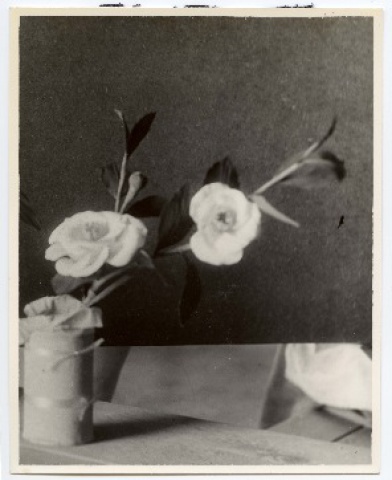

Ikebana was an important art form in all ten concentration camps, lining shelves and resting on tables in the living quarters of detainees. At risk of over simplifying this complex and deeply theoretical art form, ikebana is grounded in the belief that the lives of flowers and the lives of humans are inseparable, with the style, size, shape, texture, and color of both arrangements and containers carrying great meaning. In addition to using empty space to communicate ideas, ikebana artists attach significance to the location of arrangements and the occasions for which they are created. Along with flowers, a great diversity of materials are used including, but not limited to: branches, vines, leaves, grasses, berries, fruit, seeds, and dried or wilted plants, each conveying meaning of their own. Imprisoned Japanese Americans demonstrated great skill adapting traditional forms of ikebana to their concentration camp landscapes.[21]

Many detainees sustained and created new bonds among themselves by exhibiting their artwork. Serving as webs of collectivities, the exhibits best demonstrated the diversity of art created by imprisoned Japanese Americans. In these display spaces, they gathered to participate in complicated, colorful, and rich visual conversations that revealed inhuman treatments, economic exploitations, and dislocations encompassed by Executive Order 9066. Displaying wide variations in terms of interests, form, materials used, and expressive style, these works of art provoked ideas, resistive practices, and strategies for improving both physical and mental conditions. Here, detainees connected and formed attachments with the purpose of improving their lots in life. Embedded in these artifacts were subversions, with detainees speaking about the control exerted on their lives. For people confined in barren and monochromatic environments, art shows also offered counter landscapes, adding vibrancy and color to camp palates dominated by shades of tan.

Densho’s Content Director, Brian Niiya, adds that “exhibitions of the type that Dr. Allen H. Eaton intended did in fact take place, even if his planned exhibition did not. Perhaps Eaton and others who wanted to facilitate incorporating Japanese Americans into mainstream American communities saw art as a relatively benign way to introduce Japanese Americans to the places where they were being encouraged to resettle, possibly drawing on existing stereotypes of Asian/Japanese proclivity for the arts. A number exhibitions that included inmate art—both individual shows by the likes of Henry Sugimoto and Miné Okubo and group shows—toured the country in the resettlement and early postwar period. I describe this briefly in the Museum Exhibitions encyclopedia article, but it is an understudied topic.”