May 18, 2015

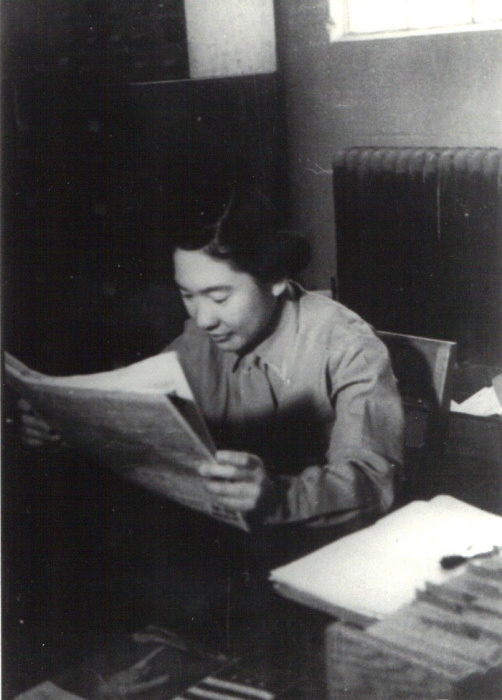

Today marks the 100th birthday of Dr. Tamie Tsuchiyama–the only Japanese American woman to work full-time for the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) Although she never published anything on mass incarceration, Tsuchiyama kept an extensive “sociological journal,” and generated a series of short ethnographic reports that have been utilized by later generations of scholars.

Here, Dr. Lane Hirabayashi, who wrote a critical biography about Dr. Tsuchiyama, highlights her involvement in wartime research and argues that her experience illustrates how race, class, and gender operated in terms of the traditional relationship between a Euro-American professor and researcher, and an aspiring person of color who was hired as an assistant.

Born in Hawai’i, the late Dr. Tamie Tsuchiyama was an unusual Nisei, or second generation Japanese American. While still a doctoral student at U.C. Berkeley, she became the only Japanese American woman who was hired as a full-time field worker by anthropologist Dorothy S. Thomas for the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS). Although she could have returned home to Hawaii, Tsuchiyama decided to let herself be incarcerated in Poston, partly with the idea of studying first-hand what was going on.

For the next year, Tsuchiyama did extensive fieldwork in Poston’s Unit I; kept a wide-ranging sociological journal; and composed a number of topically-specific ethnographic reports for Dorothy Thomas. Because she wanted to avoid being labeled as a spy for the government or the WRA, she kept her research activities a secret. Despite her constant level of data production, by 1943 Tsuchiyama’s letters to Thomas began to delineate the tremendous stress that she was experiencing as a clandestine fieldworker in Unit I. Tsuchiyama began to complain about the intolerable Poston heat, the pressures of getting access to inside information, and having to write high-quality reports. Eventually, the pressure became too much. Tsuchiyama sent in her letter of resignation in July 1944, and sought release from Poston in order to join the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps [WAAC].

She returned to Berkeley in 1947 and within a year completed her doctoral dissertation–the first sustained study of Athabascan folklore. In doing so, Tsuchiyama became the first Japanese and Asian American to earn a PhD in Anthropology from U.C. Berkeley. Unable to find a job in this discipline, however, she returned to Cal to earn yet another degree, this time in Library Science, and subsequently worked as a librarian at the University of Texas until she retired.

In 1999, I published The Politics of Fieldwork: Research in an American Concentration Camp, a book that that detailed Tsuchiyama’s trajectory led her to the WCCA camp at Santa Anita, and then to the WRA camp at Poston (the so-called “Colorado River Relocation Center” in Arizona). Here, I would like to articulate the reasons why I worked on Tsuchiyama’s biography and why it seems like a worthwhile effort more than a decade and a half later.

The Politics of Fieldwork is actually a product of an ongoing set of conversations I had with the late Yuji Ichioka, a path-breaking scholar in Japanese American studies. In the mid-1980s, Yuji indicated that since almost nothing was known about the only Issei who was employed as a researcher in Thomas’s JERS project, Richard S. Nishimoto, I should redress this and detail Nishimoto’s background and his specific contributions to JERS. Hoping to put Nishimoto’s biography and his vast collection of JERS field notes, reports, and letters into the wider context of the project, I worked on this task, on-and-off, for a decade.

Once published, my book on Nishimoto and his JERS research—titled Inside an American Concentration Camp (1995)—naturally led to Tamie Tsuchiyama. Tsuchiyama had, in fact, brought Nishimoto to Thomas’s attention and for a while he worked with Tsuchiyama doing research in Poston. As it turned out, Tsuchiyama’s life after the war was even more mysterious than Nishimoto’s. By the late 1990s, however, a revelation presented itself. Tsuchiyama’s story was a perfect example of how exploitation and resentment results when a student of color takes risks to collect data for a senior European or Euro-American scholar, who then subsequently “drops” the student as if they were a recalcitrant employee. Specifically, discovering that Thomas professionally threatened Tsuchiyama when the latter objected to the pressures she was being subject to in Poston both surprised and shocked me.

Now, fifteen years after writing about this sad and problematic history, what has changed? For one, Tsuchiyama’s name and accomplishments have been reinscribed on the historical record. Resources such as her JERS field notes about Santa Anita, Poston, and fieldwork in American-style concentration camps have recently been put on line via the Calsphere web site, which will certainly encourage their further use.

Perhaps most gratifying is that accounts of Tsuchiyama’s experiences have now been reported in the literature on the ethics and politics of fieldwork. Books with substantive passages include David H. Price’s Anthropological Intelligence (2008). Research articles citing Tsuchiyama’s work for JERS include E. Guerrier’s “Anthropology in the Interests of the State” (2007), and T. Middleton and J. Cons’ “Coming to Terms: Reinserting Research Assistants into Ethnographies Past and Present” (2014), which introduces an entire special issue on this topic in the scholarly journal Ethnography. Tsuchiyama’s story even appears as a case study in widely utilized introductory textbooks such as Cultural Anthropology: Asking Questions About Humanity.

So on her 100th birthday, I am grateful to Yuji Ichioka for suggesting that the Japanese American fieldworkers for JERS were worthy of sustained study. I am grateful to my colleagues who have foregrounded Tsuchiyama’s story in their own work. Most of all, I am grateful to Dr. Tamie Tsuchiyama. She may be gone, and never have gotten what she deserved as a scholar, but we can still learn from her travails, both before and after the war.

—

Lane Ryo Hirabayashi is a full professor in the Department of Asian American Studies at UCLA, where he is also the inaugural “George & Sakaye Aratani Chair in Japanese American Incarceration, Redress, and Community” (2006 to date). In addition to authoring numerous books, he is a regular contributor to the Densho Encyclopedia.

Read more about Tamie Tsuchiyama in the Densho Encyclopedia.