December 4, 2025

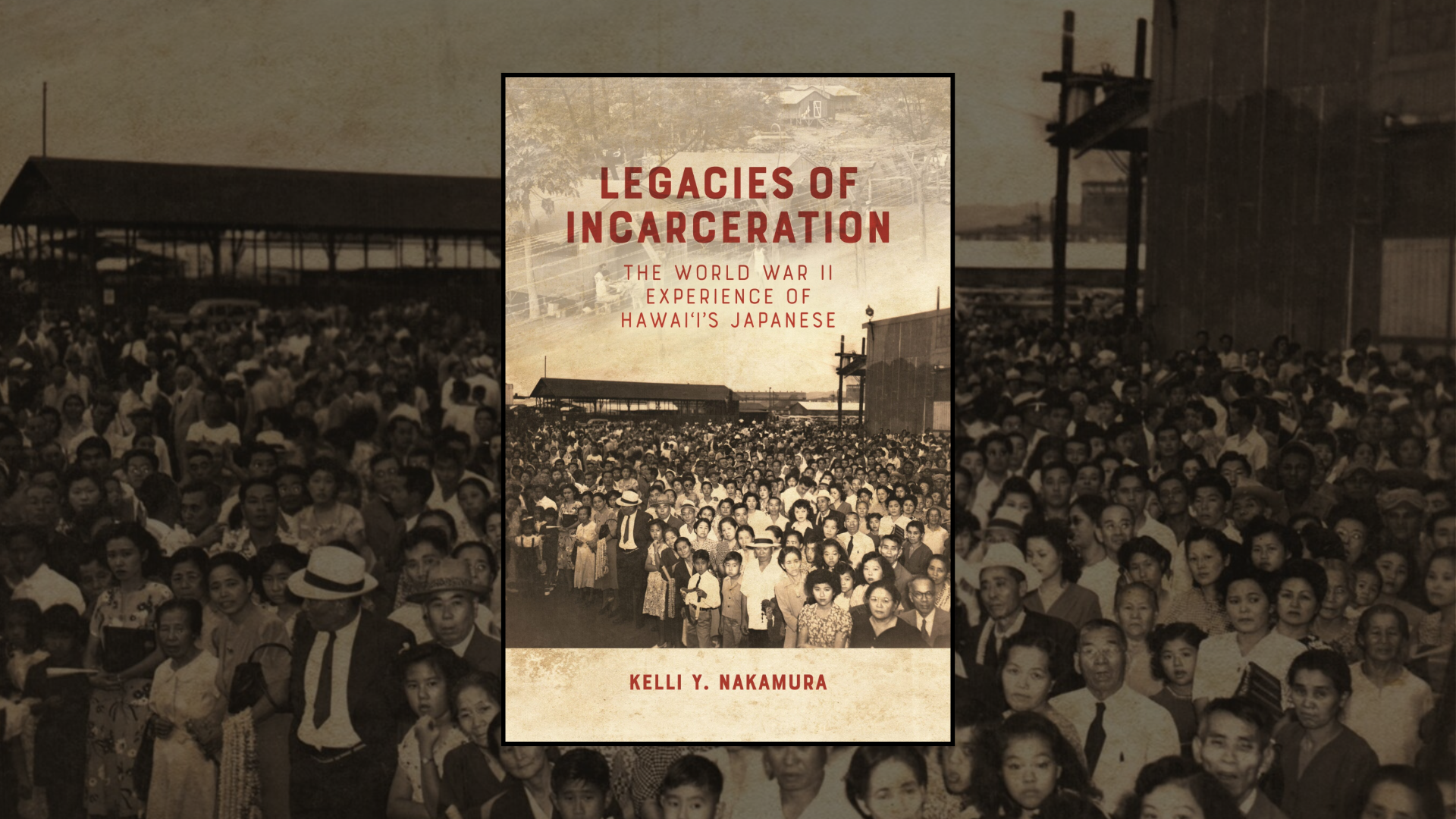

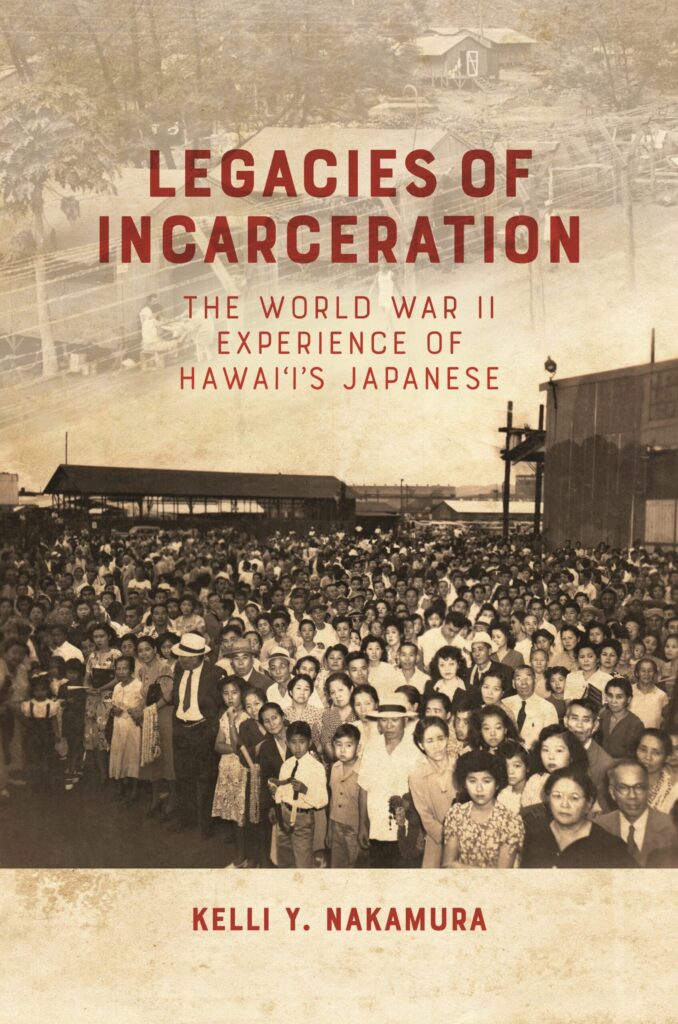

Historian Kelli Y. Nakamura’s new book, Legacies of Incarceration: The World War II Experiences of Hawai‘i’s Japanese (University of Hawai‘i Press), explores the incarceration of Japanese Americans in Hawai‘i across the different Hawaiian islands, in the context of martial law and the legacy of Hawai‘i’s plantation economy. Nakamura, a prolific contributor to the Densho Encyclopedia and an interviewer for many of Densho’s Hawai‘i oral histories, joins Densho Content Director Brian Niiya for a discussion about the book’s long journey to publication, some key insights she learned in conducting the research, and its current relevance.

Brian Niiya: Can you give me the elevator pitch, what the book is about in a paragraph?

Kelli Nakamura: Legacies of Incarceration is about the incarceration experience of Japanese and Japanese Americans in Hawai‘i during World War II. And it not only encompasses the World War II period, but I also argue that incarceration and treatment of Japanese Americans was influenced in part by the plantations and their plantation experience. So, this book examines, essentially, the pre-war conditions, particularly on the plantations, that gave rise to a unique kind of incarceration experience in Hawai‘i, which was also very different from the mainland Incarceration centers, in part because of the diversity of incarceration experiences and facilities utilized in Hawai‘i.

BN: Great, yes. I think it’s really valuable because there has been a fair amount of stuff on the incarceration and internment of people from Hawai‘i, but it’s mostly focused on the ones who went to the mainland. And I think yours is one of the first that is specifically focused on the incarceration or internment experience in Hawai‘i.

KN: That is correct. So what you often see is that Hawai‘i is often a footnote to the overall incarceration experience in the continental United States. Incarceration here in Hawai‘i is kind of seen as a preliminary step before the overall incarceration. But what I try to do is examine the treatment of individuals, not only as they are transferred across the various incarceration sites here, across the various islands, and eventually to O’ahu—and yes, we do see a large number of them actually being sent off to mainland incarceration centers—but in Honouliuli, for example, we do know that about 800 prisoners there were Japanese and Japanese Americans. So yeah, it’s a very different shift in perspective that, I think, provides a wider lens for understanding the diversity of the incarceration experience.

BN: I don’t think I’ve ever asked you this, but how did you first get interested in this topic, however many years ago?

KN: Oh, I think that’s a great question that you asked! This is a testimony to the turtle actually finishing the race. So, this is a story of failure and rejection: for the next nearly two decades [after writing my dissertation], getting rejected, rewriting, just going through this very humiliating but very educational process of having to revise, rewrite, reinterpret what you had studied during your graduate program. And what actually came about was, I realized, that this rejection was very enlightening. I mean, it wasn’t fun during the whole process. But, I encourage anyone, please don’t get discouraged: write journal articles, get that peer feedback.

Of course, working with you folks here at Densho, as I mentioned in my acknowledgements, was part of the best postdoctoral education I could ever have. Having to get that kind of nuanced understanding about the various individuals, events, legal codes, or legal restrictions really opened my eyes to a broader context. So, this was a process nearly two decades in the making.

And as for the formal writing process, it actually started in 2020. And, of course, as everyone knows, 2020 is a great year, because 2020 was the start of COVID. And, I’m going to be very honest with people, 2020 was also the year that my marriage imploded. So, in 2020, we were shut down, my marriage fell apart, I was going through this process of a divorce, and if you know anything about the process of divorce—or have experienced it, or seen it, or witnessed it—you will know that it is a very destructive process. The dream or the future that you foresaw or that you had anticipated creating is ended, or is in the process of ending.

And so, I had nothing to lose, and I wanted to create something during a very, honestly, destructive period in my life. But I had no money, I had all of my thoughts, and my life was falling apart, and I thought, what better time to write when I have absolutely nothing to lose?

So, before people think this was a virtuous endeavor, given all the free time I have from COVID, it was a response to create something during a time when literally my life was falling apart. And not to say that a divorce is the same as incarceration or internment, but I had greater empathy and understanding. When I’m reading these oral accounts about when people’s lives fell apart, when they’re separated from their spouses, physically, often, their entire livelihoods were destroyed. The future that they had envisioned and had prepared for themselves was no longer available to them. So, this came out to be what, for many people, was, I think, a very difficult time in their lives.

And this is not, again, a victory lap to say that 2020 was the best year of my life. It was actually one of the hardest years. But writing a book is a tangible product that you can at least look back on and say, I was able to salvage some good from a terrible situation. And this is what you see even in looking at the incarceration experience, how people derive meaning to salvage something out of a terrible experience or terrible process. And as we both know, having studied this as scholars, some people never recovered. Some people lost everything.

BN: The other thing that’s going on is that between the time of your dissertation and the book, there were these developments that happened regarding our knowledge of the incarceration story, the whole thing that was going on at Honouliuli—the recovering of the site, and the National Park Service, and all that stuff—and a bunch of memoirs and other publications came to the fore. So you literally could not have written this book 20 years ago, because a lot of things happened in between then and now that probably benefited what you eventually wrote.

KN: I couldn’t have timed this better, and I did not do this deliberately, but 2025 is the 10th anniversary of the designation of Honouliuli as a national park, which is an ongoing project, to be perfectly honest. So you’re right, I mean, this story could not have been written 20 years ago anyway, without the rediscovery of these sites, the recognition of their importance, the rediscovery of these internee or inmate accounts that have been published successively—Furuya to Soga to George Hoshida, out in the Big Island or Hawai‘i Island. I mean, it really was a culminating project, bringing together essentially all of these individual stories and an effort to provide a holistic understanding of the diversity of experiences.

So, you know, we were talking earlier about Gary Okihiro, and Cane Fires came out decades earlier, and that was kind of the seminal book that really enlightened a larger audience to the Hawai‘i story. It is a great scholarly work that discusses the underlying steps, or stages, that the military, and essentially the FBI, took to investigate these individuals. The story ends, of course, with these individuals being sent off to mainland incarceration centers. And so what I want to do is provide a larger story to that, at least a greater context to that, to explore not just the military aspect of it, but also the plantations, and the actual incarceration experience, and later, a little bit beyond, although I leave that for other scholars actually to pursue.

BN: Yes, that was the impression I got reading your book. It really feels like the successor or the sequel to Gary’s book, you know, in the sense that he took the story to a certain point, but there’s this whole other part of the story that he didn’t include, which he, at the time he wrote, couldn’t have included. You really tell that other side of the story, so it feels like, yeah, the second half—or maybe the second of three parts, since there is probably a part three there as well.

BN: Was there anything in particular that you found particularly challenging, or to put it another way, things that you really wanted to know but just couldn’t find the sources for?

KN: I’m still working to provide greater context and understanding of the women’s experiences. That story needs to be delved into a little more. I know scholars have tried to explore the experiences of women, but in unique kinds of circumstances. I see incredible work and scholarly treatment of experiences of women and their day-to-day kind of challenges, for example, of childbirth, of getting milk for their children, or menstruation. These kinds of day-to-day questions that we don’t think about, I think, would provide greater nuance to the challenges that these inmates face on a very humanistic level. Something as basic as nutrition, menstruation, or even the proper restroom facilities?

I mean, when you’re talking about a POW camp, [the population is] at least 95% men. Did they accommodate you [women] to have separate restroom facilities? Do they allow you to have that privacy? I mean, these are the things that I contemplate or think about late at night. In a facility predominantly built by men for male prisoners, what does it mean to be one of the few females there? How will that shape your experience? How would that separation from your family and children impact you in a way that might be different from your male counterparts?

BN: I think we’re always asked about the relevance of this history to stuff that’s going on today, and I’m sure you get asked that all the time too. But I guess what I want to ask you is how, if at all, did current events influence the way you wrote the book, or things that you talk about in the book?

KN: Unfortunately, it seems that my book came about at a very appropriate time of racial profiling, of incarceration without just cause, with the fear of immigrants and so-called alien influences here in our country, and how, simply by virtue of race or religion, an entire group can be considered suspect. Unfortunately, I would like to say we’ve made a lot of progress, but it is, in part, a historical precedent for what we’re seeing currently. So while we do not have the same degree of raids or immigration officials coming down into ethnic communities, for example, in places like California, we are still aware of it, even here in Hawai‘i, where the majority are minorities. The fact that it is eerily premonitory of what is going on still today.

I talked about how I had worked with federal agencies, and even to describe what I do, I had to eliminate the words or the phrase that I studied—race and ethnicity—from my biography. I said, absolutely, I understand, and a lot of people feel uncomfortable talking about certain parts of history. That doesn’t make it disappear. Or the fact that we don’t use it as a place of shame, per se, like we’re trying to criticize contemporary groups or contemporary society, but rather as a place to grow and do better, and learn from.

It’s not about making people feel bad about past events, but about helping them do better.

—

Kelli Y. Nakamura is a History Professor at Kapi‘olani Community College. Her research interests focus on Japanese and Japanese American history, and she has published articles in the Journal of World History, Amerasia, The Historian, and the Hawaiian Journal of History. She also teaches at the Ethnic Studies, Women’s Studies, and History Department at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, focusing on gender and race during World War II.

Purchase the book here.