October 10, 2025

October is American Archives Month, which means it’s a fitting time to explore how educators and students can use Densho’s archive to teach and learn about Japanese American wartime incarceration. Courtney Wai, Densho’s Education and Public Programs Manager, sat down with Densho’s archivists and oral historians for a conversation about the values that guide their work and how those values can shape classroom practice.

What Does It Mean to Preserve and Share Difficult Histories with Care?

That question has guided Densho since its founding in 1996. That compassion is evident in the Densho Digital Repository, where survivors and families share deeply personal documents—diaries, letters, photographs—and retain agency over how their stories are preserved and accessed. Even in Densho’s earliest oral histories, interviewers created space for survivors to grapple with painful memories on their own terms. As Digital Archivist Sara Beckman reflected in our first post, “An Educator’s Guide to Searching the Densho Digital Repository,” the archive is built on trust, compassion, and connection with the Japanese American community.

Educators, like archivists, are also stewards of memory. Archivists preserve history so it can be shared; teachers bring that history to life. By adopting Densho’s values of care, stewardship, trust, and criticality, educators can help students engage with difficult histories in ways that are both compassionate and critical.

Care: Honoring Community Voices

At Densho, survivors and descendants who share stories and materials retain ownership and agency. Densho follows a post-custodial or “catch and release” approach: families keep their originals, while Densho digitizes them for public access. This model encourages participation while respecting consent and ownership.

Because these collections often document experiences of racism, trauma, and exclusion, the Densho team uses a trauma-informed approach that centers care and transparency. Families shape what gets preserved and how it is represented. The result is a collection that reflects the diversity and humanity of Japanese American experiences during incarceration.

Educators can draw from this same approach. Teaching difficult histories require balancing trauma with resilience, showing how communities survived, organized, and created meaning in the face of injustice. By using sources created in collaboration with the affected communities, teachers can model respect and avoid curricular violence that reduces people to suffering alone.

Stewardship: Teaching the Full Story

Densho’s strength lies in the breadth of its collections: small family contributions that, together, offer a wide diversity of perspectives. Oral historians invite narrators to share their full story, guided by active listening. Archivists describe objects at the item-level to preserve accuracy and nuance, ensuring that stories are accessible to audiences. Tools like the terminology guide ensure respectful and historically accurate representation. For example, Densho recommends using terms like “removal” instead of euphemisms like “evacuation,” which frames and makes visible the realities of forced displacement.

Educators can mirror these commitments by teaching the full story—not just through powerful figures, but through everyday lives captured in personal materials. By engaging students with primary sources that reflect diverse perspectives on historical events, educators can help them understand both what happened and how individuals and communities experienced it differently.

Teaching difficult histories also means situating events in their broader context. The Holocaust, for instance, cannot be fully understood without exploring the deep history of antisemitism or the many forms of Jewish resistance.1 Rosa Parks is remembered as a lone woman making a spontaneous choice, rather than part of a larger movement. Likewise, the incarceration of Japanese Americans is frequently framed as a wartime “necessity” after Pearl Harbor, without reckoning with decades of anti-Japanese racism that preceded it—or the activism that led to the hard-won victory of redress.

When educators teach a fuller history—root causes, systemic forces, community agency, and critical language—they honor the complexity of the past and equip students to think critically about the present.

Trust: Honoring Agency and Multiple Truths

Unlike many archives that prioritize official records, Densho’s collection holds multiple perspectives on the same events, sometimes even contradictory ones. Processing Archivist Dina Moreno explains, “how people experience an event is as important to the story as the factual details.”

By the time Densho started collecting oral histories, many survivors had passed away, leaving behind those who were children during the incarceration. Their memories included the fun they had at camp, which can feel at odds with their actual circumstances. Moreno explains, “Two or more things can be true at the same time. Someone can say they had fun living in camp and still acknowledge the injustice of incarceration, and understand that not everyone experienced it the same way. If all those lived and understood experiences are available to see and read, the story is actually a more accurate representation of history.”

In the classroom, this same principle applies. Students are capable of holding complexity and nuance. Sources may conflict with each other and perspectives may differ, but teachers should help students grapple with difference rather than seek one definitive version of history. Encouracing students to view history through the various perspectives nurtures both empathy and critical thinking.

Criticality: Teaching History as Contested, Constructed, and Connected

Densho’s collections remind us that history is never neutral. Government records often present incarceration as orderly or justified, while family photographs, diaries, and oral histories reveal the loss and painful realities of confinement behind official language. Archivists at Densho make these biases as part of the historical record itself.

Archives, like classrooms, are sites of interpretation. As Caitlin Oiye, Archives Director, explains, “Primary sources aren’t necessarily ‘the truth’ because they’re just a document that explains what was happening at that time to that person. True or not, it’s important to go back to the source and who wrote it, analyze more than just one document, and know the context of history.”

For educators, teaching with criticality means helping students connect the past to the present: not only its legacies of oppression, but also the many ways people resisted and built community in the face of injustice.

Carrying the Work Forward

Care, stewardship, trust, and criticality aren’t only the values that guide Densho’s archives—they can guide how we teach any difficult history. When educators approach teaching difficult histories with these commitments, students gain more than just information. They learn to see history as lived experiences, to honor community voices, and to question the narratives that shape our world.

Teaching difficult histories with care help students recognize that how we remember the past is inseparable from how we radically imagine and create a more just future.

—

This post is the second in a three-part series on teaching with the Densho Digital Repository. Next, we’ll close the series by highlighting Densho’s recommendations for pedagogical approaches to teaching Japanese American wartime incarceration.

Footnotes

- Simone Schweber, “Holocaust Fatigue in Schools Today” in Social Studies Today: Research and Practice Second Edition. ↩︎

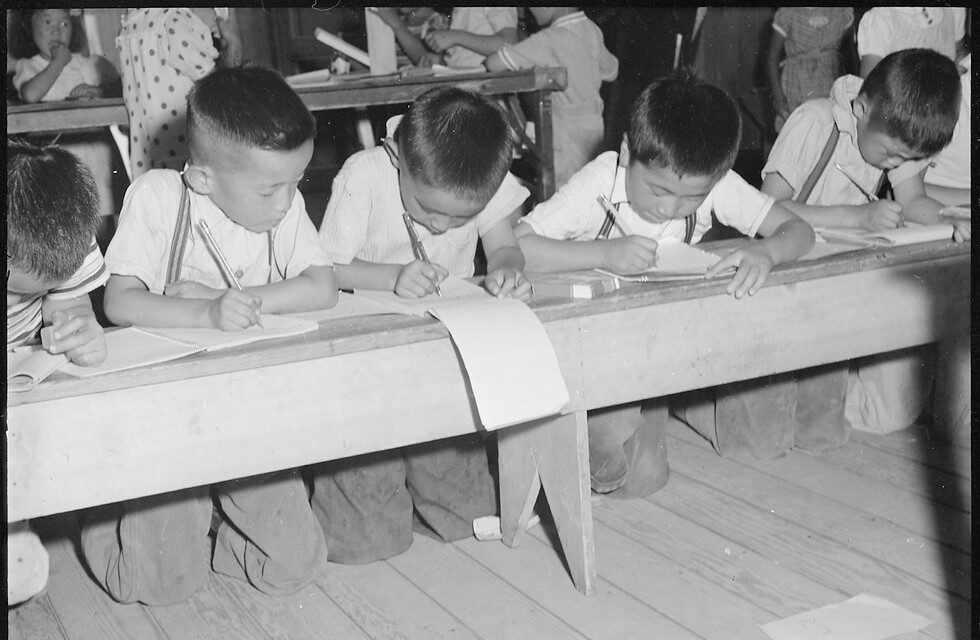

[Header: Elementary students studying in a makeshift classroom inside Manzanar, 1942. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]