October 1, 2025

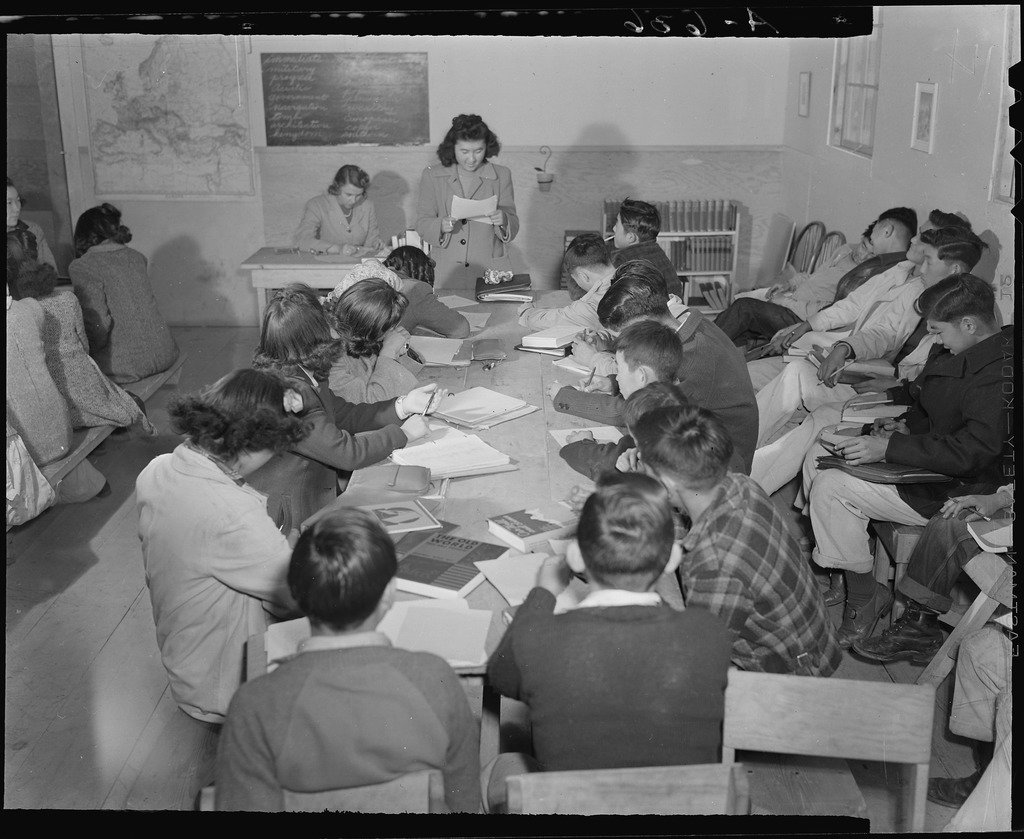

October is American Archives Month, which means it’s a perfect time to highlight how educators and students can use Densho’s archive to teach and learn about Japanese American wartime incarceration. Courtney Wai, Densho’s Education and Public Programs Manager, sat down with Sara Beckman, the Digital Archivist at Densho, for a conversation and virtual tour of Densho’s archives. Together, they explored how educators and students can effectively search Densho’s archives, make the most of primary sources like oral histories, photographs, and diaries, and discover tips, strategies and hidden gems that can enrich their teaching and students’ learning.

This post is the first in a series exploring how to teach using the Densho Digital Repository. Stay tuned for additional tips and resources!

Courtney Wai: Can you give an overview of what’s in the Densho archives and what makes this collection unique?

Sara Beckman: Densho is what’s called a post-custodial archive, which is the fancy way of saying that we use a catch-and-release approach, if you think about it in fishing terms. Instead of a traditional archive, where you would give your materials and that archive would keep them forever, we receive our materials as a loan. You loan them to us so we can go through the digitization process, scan everything, and then once we’re done with that, we return them to you. This allows people to get their things digitized so they don’t feel like they have to give them up, and it allows families to share things they would never want to permanently give away. That makes us really unique.

Then everything goes up on our website, and the family really works with us as partners. There are things that, as archivists, we always redact—like modern addresses or health information—but we also really work with families about what they want online. For example, some families may not want to share letters or photos. I’ve redacted lines out of family letters before because the family didn’t want certain details known—things like little family tiffs. They might be part of the historical record, but you don’t want to find out about a family argument between your aunts and uncles on the internet.What’s in the archive is what people give us. We cover topics from immigration—sometimes as early as the late 1800s—through pre-war, wartime, and post-war. Then we move into the redress and reparations movement in the 1970s and 1980s, and we also have more modern materials, from the pilgrimage movement through the present day.

CW: For educators who are new to the Densho Digital Repository, what are some basic tips or strategies for searching?

SB: Always remember it’s not Google. We’re always thinking in terms of keywords instead of full search phrases—that’ll help you get better results. Always use our filters; they’re a great way to narrow down to what you’re actually looking for.

Also, don’t give up after the first search. Be creative with your terms—try synonyms, because the way you think of something might not be the way we’ve catalogued it. Use the Browse features if you don’t have something specific in mind but want to explore a topic, like finding photos about a job or daily life. Browsing Topics makes more sense for broad searches, whereas the search bar is better if you’re trying to find something very specific.

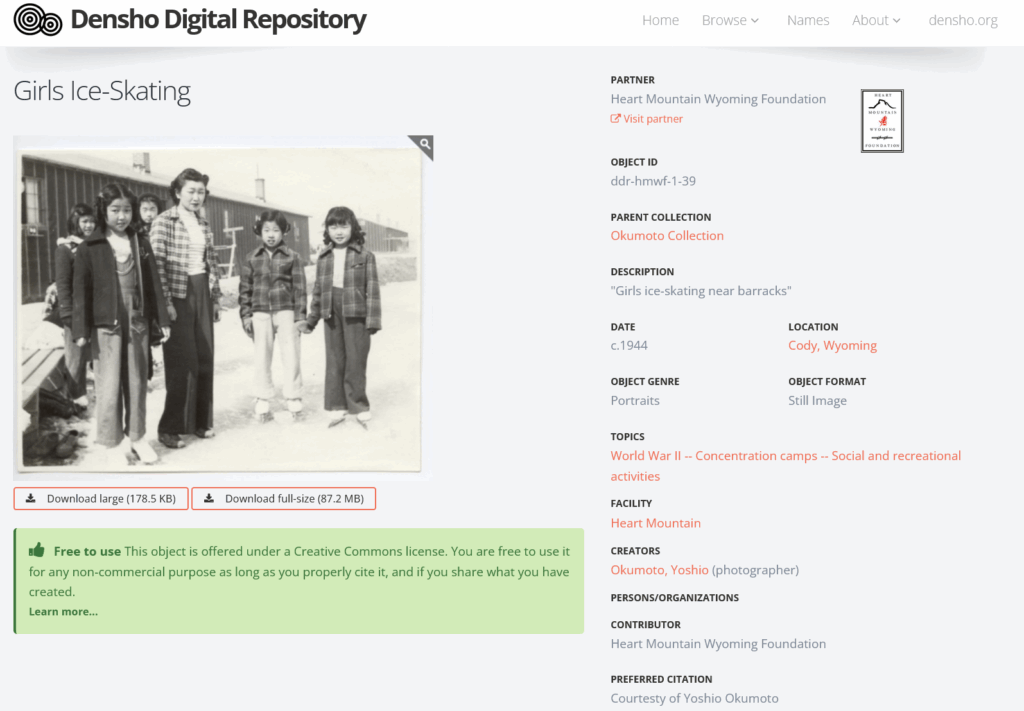

CW: I’ve also noticed that anytime you click on something in the Densho Digital Repository, like a photograph, it has a preferred citation. Can you tell us more about this?

SB: Yes! If you’re using something in, say, a slideshow, we have what we call a “courtesy line.” It says “Courtesy of [collection name], Densho.” For example: “Courtesy of the Yasui Family Collection, Densho.” That way people know exactly where it came from. We do have a page about citing material from the DDR. You can find it at ddr.densho.org/using. And our URLs are user-friendly—everything is ddr.densho.org/[ID number]. They stay consistent and take you back to the exact collection and object. It’s not a ridiculously long URL full of random numbers and letters.

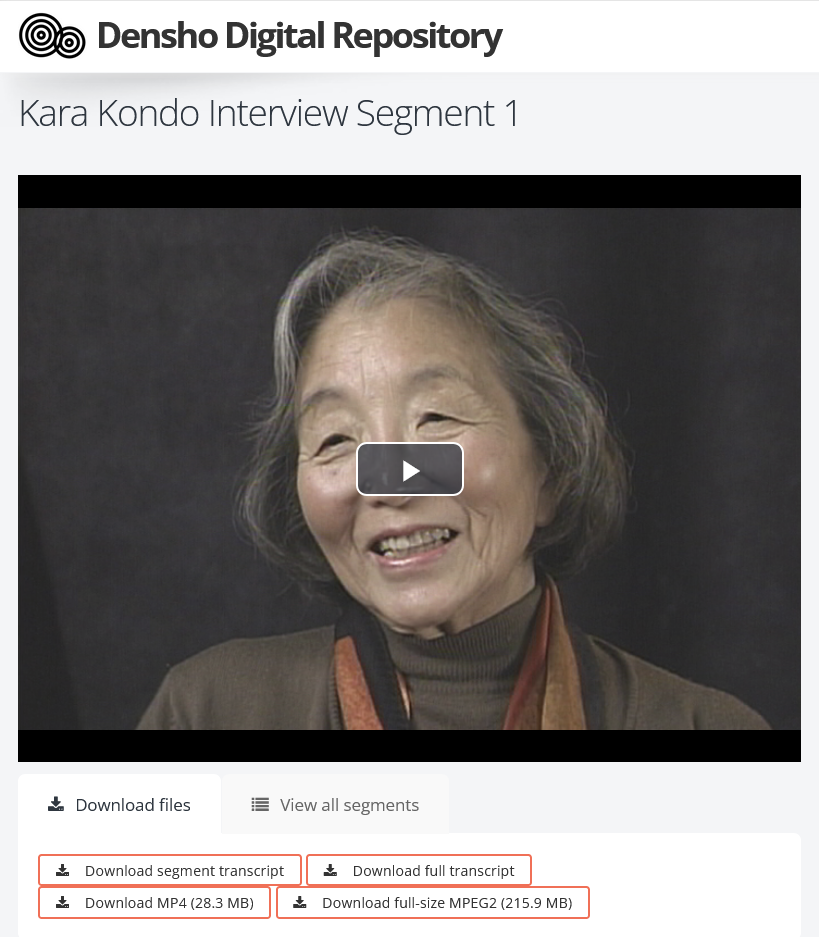

CW: Oral histories are also a big part of the Densho Digital Repository. If someone wanted to use an oral history, what are some tips for searching and using them effectively?

SB: One great thing is that we segment our oral history videos by distinct topics. If you don’t have time to sit through a two-hour interview, you can jump to the clip about a subject you’re interested in—say, reactions to Pearl Harbor. You can search “Pearl Harbor” and find clips of different people describing how they learned about it, what happened that day, and how their families were affected.

If you find someone compelling, you can then navigate forward and backward through their full interview on the same page, since all the segments are connected.

Another key feature is that everything is transcribed. I can read faster than someone can talk, and transcripts are great for research. You can download a whole transcript, or just a segment. That’s especially useful for students—it’s less overwhelming to start with a short segment rather than 20 pages of text.

It was revolutionary in the 1990s when Densho decided to preserve not just transcripts but also the audio and video. Traditionally, oral historians saved only the transcript. Saving the video and audio preserves tone, emotion, and presence. It’s moving to actually hear people’s voices and see them, which keeps students more engaged.

CW: Many teachers want their students to go beyond the textbook. How can educators use these search skills not only with Densho, but with other archives?

SB: Thinking in keywords is a universal skill. Any archive database will work that way, whether it’s Densho or somewhere else. Teaching students to brainstorm multiple search terms, to try synonyms, and to persist beyond the first page of results is crucial.

Searching in archives isn’t easy—you have to dig. Just like with physical materials, it takes persistence and flexibility. Don’t expect to click one button and have the perfect result pop up.

CW: What are some hidden gems or underutilized parts of the archive you wish educators knew about?

SB: I think our journals and diaries are really underutilized, partly because they’re hard to tag. We have three- and five-year diaries from the 1940s, where people wrote daily entries. Sometimes they’re simple—like a farmer writing, “Today was 65 degrees and we worked in field B.” But that’s valuable! Historians might use it for weather data, for example.

And then there are quirky surprises. I once processed a World War II GI’s photo collection from Europe, and there was this mysterious white woman who appeared in several photos. Later the family came back with translated letters—she was his French girlfriend. That kind of discovery makes archival work exciting.

We also had a diary from a white woman in Seattle who worked in social services during the 1940s. She was conflicted about helping identify Japanese Americans for removal while also living among them in her boarding house. Her descendant felt she was complicit, but reading her journal shows she struggled to do things as humanely as she could. Seeing those two perspectives side by side was fascinating.

CW: What additional advice do you have for teachers and students when citing Densho materials?

SB: When you’re doing research with Densho, everything you can use for your school project falls under fair use. If you’re doing something like a school report, slideshow or a presentation, you can still use those materials under fair use for educational purposes.

Now, when it comes to something a bit more creative, like if you are doing a remix of something, making a music video, or doing something that transforms it a bit more, I would say you might want to stick more towards the things that are free to use under our Creative Commons license, which explicitly allows for transformative works. For example, if you’re doing a podcast and you’re taking clips out of our oral histories, I would use the oral histories that have our Creative Commons License.

CW: From your perspective, how does learning to search archives build students’ historical and critical thinking skills?

SB: Searching archives helps students think more flexibly—using synonyms, considering how language changes over time, and recognizing that words meant different things historically. For example, “diary” might mean a journal, or it might mean a date book or calendar.

In the Japanese American community, language calcified in unique ways. Immigrants came speaking Meiji-era Japanese, which evolved differently from modern Japanese. Their kids learned that older form at home. So we often need historians familiar with that specific language to translate.

It’s also fun to see slang in letters—like 1940s teens using expressions we thought were just stereotypes from old movies. It shows language evolving in real time, and it makes history feel alive.

CW: With the rise of artificial intelligence (AI), why is it important to still teach students how to search and use archives directly?

SB: AI is only as smart as the information it scrapes. If it scrapes something inaccurate, it can repeat it as fact. Garbage in, garbage out.

Students need to learn to go to primary sources, to see what people actually said at the time. For example, one of my coworkers saw an AI response to a search for Casa Grande and Gila River that said the train ride was pleasant. When looking closer at the primary source, they said the train ride was pleasant enough when compared to the bus ride and it was the opinion of a child, which is very different from an adult reaction with adult worries. Also later when we tried to find this AI answer again it changed! Which on one side is good because the AI response was more accurate now, but for research it is bad because you couldn’t replicate what you found or figure out where that quote or information came from if you didn’t look into the primary source the first time.

That’s why searching and reading the sources yourself is so important. AI is a tool, but it can’t replace careful research.

Alongside our conversation, Sara provided a video tour of the archives to demonstrate how to effectively navigate and search the Densho Digital Repository.