January 8, 2025

Continuing what has become an annual tradition as well as one of our favorite pieces to put together, here are some notable Nisei who would have turned one hundred years old in 2025—plus two soon-to-be centenarians who remain active today.

After Nisei births on the continent peaked in the early 1920, they started to come down by 1925 and would continue to gradually decrease into the late 1930s when significant numbers of Sansei began to arrive on the scene. Nisei born in 1925 would have been in high school when World War II began and most in this group graduated from high school in a concentration camp. As with their older brothers, many of the men served in World War II, though fewer of them given their age. Their lives all have something to teach us in a present that sometimes seems as troubled as the war years were.

Artists

We’ll start this year with the artists and with a pair of cartoonists in particular, one who is best known for his work within the Japanese American community and one who is known for his work in the mainstream world.

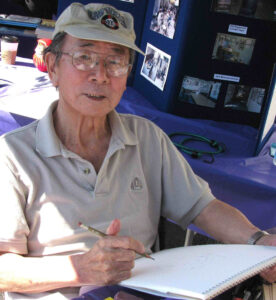

Jack Matsuoka (d. 2013) is probably best known for his collection of cartoons depicting his experiences at Poston, Camp II, Block 211, first published in 1974 as community interest in the incarceration started to rise. Based on sketches he had made while imprisoned as a teenager, they captured the variegated life of a camp teen from the travails of desert heat, communal toilets, and the loyalty questionnaire to the fun and mischief of camp dances, sports, and other recreational activities. He also did a comic strip titled “Sensei” for the Hokubei Mainichi and also worked for various mainstream publications as well as for the San Francisco Giants and 49ers. He spent over a decade in military intelligence in Japan after the war and his first published collection was on the life of American G.I.’s in Japan.

Though you may not know his name, if you are a baby boomer or Gen Xer, you undoubtedly know some of the characters that Iwao Takamoto (d. 2007) created, including Scooby-Doo, Muttley, and Penelope Pitstop. Born and raised in Los Angeles and incarcerated at Manzanar, he was hired by Disney in 1945 and worked on films such as Cinderella, Lady and the Tramp, and One Hundred and One Dalmatians before leaving for Hanna-Barbara in 1961. Over the course of some forty years there, Takamoto was a key figure in establishing the visual style of the company that dominated animated television in the 60s and 70s.

The similarly named artists Emiko Nakano (d. 1990) and Momo Nagano (d. 2010) both grew up in California and both graduated high school in concentration camps, the former in Amache and the latter in Manzanar. Nakano, who became an assistant art teacher at Amache after graduating, painted scenes at Amache and Crystal City, where her family was later transferred. Settling in Richmond, California after the war, she attended the California School of Fine Arts and became well-known locally for her abstract oil paintings and prints. Mostly active as an artist in the 1950s, she also worked as a fashion illustrator.

After leaving Manzanar to go to college in Massachusetts, Nagano returned to Los Angeles where she studied ceramics while raising four children. Turning to weaving in the 1960s, she became renowned for her large-scale works that appeared in numerous exhibitions and were incorporated into local architectural projects. Ironically, one of her experiences in weaving came at Manzanar, where she was among the workers at the camouflage net factory there. She also taught and worked at the Doizaki Gallery of the Japanese American Cultural and Community Center in Los Angeles in the 80s and 90s.

Entertainers

“Entertainers” is a broad way to group four very different lives, two of whom were well-known within the ethnic community and two who were better known outside it. We’ll start with the first of the latter pair.

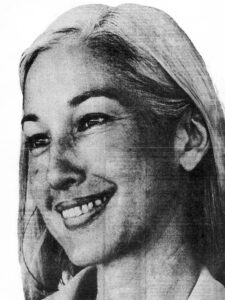

Miiko Taka (d. 2023) was born Miiko Shikata in Seattle, but mostly grew up in the “Uptown” neighborhood of Los Angeles (now Koreatown). Forcibly removed with her family to Santa Anita and Gila River, she graduated from Butte High School in the latter in 1944 before resettling in Chicago and later moving back to LA with her husband and two children. It was there, according to studio publicity at least, that she was “discovered” at Nisei Week by a Warner Brothers talent executive who was looking for the female lead for the studio’s adaptation of James Michener’s novel Sayonara. Auditioning for and landing the part despite no prior acting experience, the newly christened Miiko Taka starred opposite Marlon Brando in an interracial love story set in postwar Japan. Despite the film’s critical and commercial success—and the generally good reviews she received for her performance—Taka’s stardom was short-lived, as was the case for many other Asian American actors before and after her, due to the shortage of substantive roles. She did appear in smaller roles in various other Hollywood films in the 1960s and made many TV guest appearances into the 1980s, including in the original Shogun miniseries. She also was active for a time in the Los Angeles Japanese American community, particularly with Nisei Week. She spent her later years in Las Vegas.

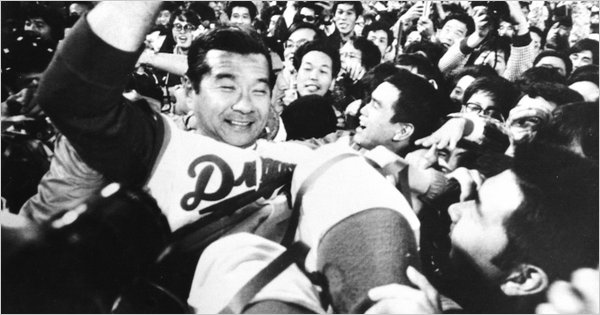

Arguably the most famous person on this list to non-Japanese American audiences, Wally Yonamine (d. 2011) was a professional athlete in two different sports. Born as Kaname Yonamine to Issei parents (his father was from Okinawa and his mother from Hiroshima) on the island of Maui, Hawai`i, he became a star athlete at both Lahainaluna (Maui) and Farrington (O`ahu) High Schools. After a stint in the army, he played football for a year for the San Francisco 49ers until a wrist injury led to his release. Turning to baseball, he played one year in the Pacific Coast League, before heading to Japan to become the first American to play professionally there after World War II. Though his aggressive style of play initially rankled opponents and fans alike, he soon became a star and fan favorite leading the Yomiuri Giants to eight championships in ten years and winning three batting titles and an MVP award. He later managed the Chunichi Dragons and was elected to Japan’s Baseball Hall of Fame.

Mary Kageyama Nomura, who will celebrate her 100th birthday in September, is a familiar name to Japanese Americans especially in the Los Angeles area. The former was the famed “Songbird of Manzanar,” whom many former Manzanar denizens of a certain age recall fondly for her singing at various high school programs as well as talent shows and dances, often accompanied by music teacher and mentor Lou Frizzell. But unlike some other Nisei who did seek out careers as singers such as Pat Suzuki (who sang as a teenager at Amache) or Elsie Itashiki (who recorded albums under the name “Teal Joy”), Nomura, who met her husband Shi Nomura at Manzanar, married and had five children and lived an “ordinary” Nisei life. However, with the rising interest in the incarceration among Japanese Americans started in the 70s and 80s, she began to sing again at various events and has become a well-known and beloved figure in the community as well as the subject of a children’s book and three different documentaries.

George “Horse” Yoshinaga grew up on a farm in Sunnyvale, California, but became strongly associated with Los Angeles thanks largely to the accident of going to camp with people from L.A., first at Santa Anita, then at Heart Mountain. A star football player in high school, he was a key member of the undefeated Heart Mountain high school team whose story was recently told in the book The Eagles of Heart Mountain by Bradford Pearson. After a stint in the army, with the Counter Intelligence Corps, he began to work at various Japanese American newspapers and began writing a column called “The Horse’s Mouth” first for Crossroads, then for the Kashu Mainichi, for which he also served as the English language editor. In 1991, he moved the column to the Rafu Shimpo. In addition to his newspaper work, he also was a sports promoter who was perhaps known for starting the Japan Bowl, an American college football all-star game played in Japan that ran from 1976 to 1993. His lengthy columns brought out both fans and detractors of his sometimes rambling style and conservative politics. He wrote his column for over seventy years and continued almost to the day he died at age ninety.

Political and Civil Rights Figures

Two very different women highlight the very different circumstances faced by Japanese Americans on the continent and in Hawai`i.

A mixed race Sansei attending Sacred Heart Academy in Honolulu, Jean Sadako King (d. 2013) remembered looking forward to her sixteenth birthday because that was when her parents would allow her to start dating. Coming as it did on December 6, 1941, there were soon other things to worry about for her and family. But unlike their West Coast counterparts, King was able to continue her prewar life and schooling under martial law, attending the University of Hawai`i and eventually completing two master’s degrees. After a stint as an aide to Tadao Beppu, the speaker of the house of the Hawai`i Legislature from 1968 to 1974, she ran for and won election to the legislature herself in 1972, then to the state senate in 1974. In 1978, she won election as lieutenant governor, becoming the first Asian American to be elected lieutenant governor in any state. Though a Democrat, she was not affiliated with the coalition built by former Governor John Burns, and she challenged incumbent Governor George Ariyoshi in 1982. After her defeat, she left electoral politics, though she remained active in the local community.

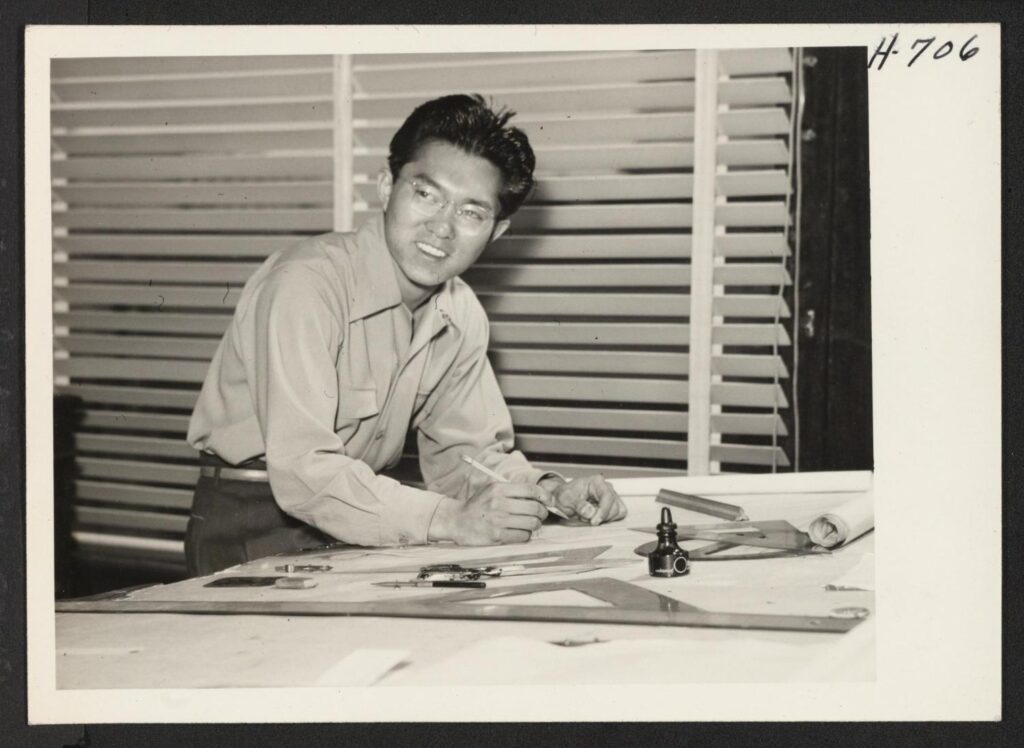

Esther Takei (d. 2019) grew up in Venice, California, the daughter of Issei parents who ran carnival games at the Venice pier. Forcibly removed from their home and incarcerated along with all other West Coast Japanese Americans, the Takeis were held first at the Santa Anita Assembly Center then the Amache, Colorado concentration camp. At Amache, she worked as a dental assistant and for the camp newspaper as reporter, columnist and cartoonist. In the summer of 1944, she was approached by Hugh Anderson, who had stored belongings of Japanese American families including the Takeis. Representing a group called Friends of the American Way, Anderson had secured permission for a Nisei student to return to the West Coast that fall as a test case before the lifting of the exclusion order. After talking it over with her parents, Takei agreed to be that test case. She arrived in Pasadena to attend Pasadena Junior College on September 12, 1944, living with Anderson and his family. Though the reception from students and faculty was overwhelmingly positive, she did face protests by local activists, though those quickly died down. Her courageous actions paved the way for the reopening of the West Coast to Japanese Americans in 1945. Largely remaining silent about her wartime ordeals for decades, she began doing oral histories (including one with Densho) and talking about her experiences in the 2000s.

Over the past few decades, perceptions of Nisei draft resisters have changed dramatically, and the next two on our list were among those who facilitated that change, one in Seattle and one in Los Angeles.

Gene Akutsu (d. 2011) was born and raised in Seattle to Issei parents. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, his father, who had been active with the local Japanese Association, was arrested and interned, ultimately ending up in the enemy alien detention camps Fort Missoula, Montana; Camp Livingston, Louisiana; and Santa Fe, New Mexico, before being allowed to rejoin the family at Minidoka in December 1943 after a nearly two year separation. In the meantime Gene, his older brother Jim, and their mother were removed to Puyallup and Minidoka. Angered by their treatment and the treatment of their father, both brothers refused to report when drafted in early 1944 and both were convicted and served jail sentences at McNeil Island Penitentiary back in Washington. They were released after serving 2½ years in April 1947. Six months after their return, their mother, depressed at the toll the war took on her family, took her own life. Gene rebuilt his life, marrying, and having three children, and working for a Seattle clothing company for over thirty years. Initially keeping a low profile, he later spoke openly about his experience as a draft resister—including two interviews in the Densho’s Digital Repository—and was one of those featured in Eric Muller’s landmark book, Free to Die for Their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II.

Takashi Hoshizaki was the eldest of six children born to Issei parents in Los Angeles, where he grew up in the area of East Hollywood known as “J-Flats.” With his family, he was removed to Pomona and Heart Mountain and graduated from Heart Mountain High School. Angered by his family’s incarceration, Hoshizaki was drawn to the message of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee once Nisei were deemed eligible for the draft and was arrested in March 1944. He was one of the sixty-three resisters from Heart Mountain tried in a mass trial in July 1944. Convicted along with all of the others, he also did his time at McNeil Island and was released in June 1946. Returning to Los Angeles, he attended Los Angeles City College and UCLA. Drafted again in 1953, he ended up serving in the Korean War in a chemical biological warfare unit and as a lab technician. With the help of the G.I. Bill, he went on to a doctorate in botanical science at UCLA in 1960 and to a scientific career that involved stints with UCLA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Active in the Japanese American community, he was one of the founders of the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center and a frequent speaker at events where he told his draft resistance story. He was a frequent writer of letters to the editors of Los Angeles vernacular newspapers, including many exchanges with “Horse” Yoshinaga that were surprisingly cordial given their differing views of resistance. He remains active as he approaches his 100th birthday, for instance, being a featured speaker at the 2024 Los Angeles Day of Remembrance among other recent appearances.

Veterans

Three of the most famous Nisei veterans were also born in 1925. Of the three, Hiroshi “Hershey” Miyamura (d. 2022) was certainly the best known until the 2000s, since he was at that time the only living Japanese American recipient of the Medal of Honor, the country’s highest military decoration. Born and raised in Gallup, New Mexico, the 4th of seven children of Issei parents, he and his family avoided incarceration since they lived outside the restricted area. Drafted in 1944, he served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, going overseas just days before the war ended in Europe. After his discharge, he enlisted in the army reserves and was recalled to active duty in 1950 and sent to Korea where he became a squad leader in the Third Infantry Division. On the night of April 24, 1951, near Taejon-ni, his squad came under attack. He killed an estimated fifty enemy soldiers while defending his outpost, allowing his men to retreat. Severely wounded, he was ultimately captured and held as a prison of war for twenty-eight months. He was released on August 20, 1953 after the Korean armistice. His return to the U.S. was much celebrated by the JACL—he and his wife had been members of the Albuquerque chapter—and by his hometown, where half the town turned out to welcome him home. He remained in Gallup running a diner and gas station until his last years and remained active in veterans organizations. A street, park and high school in Gallup are named after him.

While Miyamura was universally described as a humble and quiet man, the embodiment of the Nisei as “quiet Americans,” Rudy Tokiwa (d. 2004) was anything but that. One of six children of Issei parents, he grew up on a farm outside of Salinas, California, and was incarcerated at Salinas and Poston. He enlisted in 1943 and was eventually assigned to K Company of the 442nd, seeing combat from June 1944 to April 1945 in Italy and France. For much of that time, he was a “runner” assigned to carry messages between headquarters and field commanders, a particularly dangerous job. He was also among the first to reach the trapped soldiers of the “Lost Battalion” in October 1944. Wounded several times, shrapnel that shredded his lower body in April 1945 ended his war and kept him in pain throughout his life. He was awarded a Bronze Star in June 1945.

Settling in the San Jose area after the war, Tokiwa was active in the local Japanese American community and in veterans organizations, serving as the founding president of Go For Broke, Inc., the predecessor of the National Japanese American Historical Society, was active in the Redress Movement. During a 1987 lobbying trip to Washington, D.C., he was credited with convincing key Florida Congressman Charles Bennett—whose war wounds were similar to his own—to support the legislation. A colorful and charismatic storyteller, Tokiwa was featured in many documentaries and is one of the key characters in Daniel James Brown’s Facing the Mountain: A True Story of Japanese American Heroes in World War II.

Finally, there is Stanley Hayami, who may be the best known of the three today, especially within the Japanese American community. Born in Los Angeles, his family ran a nursery in San Gabriel, California before their forced removal to Pomona and Heart Mountain. A gifted artist, Hayami worked on the high school yearbook and took art classes from some of the professional artists incarcerated at Heart Mountain. Drafted in 1944, he reported for basic training on August 22, 1944 and eventually was sent to Europe as part of the 2nd Battalion, Company C. He died in a battle in San Terenzo, Italy and was posthumously awarded a Purple Heart and Bronze Star. In the 1990s, Hayami’s family donated his camp diary to the Japanese American National Museum. A candid look at camp through the eyes of a curious teenager and also filled with whimsical drawings, it struck a chord with the community and has since become the subject of a book, a film, and a JANM exhibition built around a virtual reality component. In death, he remains ever youthful, and I think his diary really resonates—perhaps in different ways—with young and old alike.

Though also a World War II veteran, Bill Naito became better known as a businessman and philanthropist in Portland, and is often credited for spurring the revival of the Old Town area starting in the 1960s. He was born in Portland as William Sumio Naito to Issei parents who ran successful retail and wholesale businesses. During World War II, the Naitos also became “voluntary evacuees,” leaving for Utah where they had relatives. Bill left Washington High School in the middle of class so no one would see him clearing out his locker. After graduating from high school in Utah, he served in the Military Intelligence Service in occupied Japan. Upon his discharge, he attended Reed College and went on to a master’s degree in economics from the University of Chicago. Leaving a Ph.D. program in Chicago, he returned to Portland in 1953, joining the family import business. He began to buy and renovate old buildings in the downtown area—including the old Japantown area—in the 1960s while also expanding the family business to include the Made in Oregon chain of stores. He was a key figure raising the money for the Japanese American Historical Plaza and for the Oregon Nikkei Endowment (now the Japanese American Museum of Oregon). After his sudden death in 1996, Naito Parkway was named after him.

Educators

We end with three educators, given how important the work of educators will be in the years to come.

Though not an educator by training or profession, Mary Matsuda Gruenewald (d. 2021) introduced many to the story of the wartime incarceration through her memoir and speaking engagements as a senior citizen. After a seemingly idyllic childhood on Vashon Island, Washington, she and her family were incarcerated at Pinedale, Tule Lake, and Heart Mountain. She left camp to join the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps and later spent twenty-five years as a nurse in Seattle. Like many Nisei, she spoke little about her wartime experiences, but began writing a camp memoir at age seventy in response to questions from her children. Published in time for her 80th birthday, Looking Like the Enemy: My Story of Imprisonment in Japanese-American Internment Camps was a detailed and frank exploration of her camp experiences. She followed that with a “Young Reader’s Edition” as well as a second memoir, Becoming Mama-San: 80 Years of Wisdom. She was also a frequent public speaker in her later years.

Jane Komeiji (d. 2024) and Aki Kurose (d. 1998) were both schoolteachers—an occupation that drew many Nisei women—who had large impacts on their communities over the course of their lives.

Jane Okamoto was born and raised in Honolulu, largely growing up in the `A`ala district of downtown Honolulu, a close knit cluster of Japanese American businesses. Her mother ran a successful dry goods store, and Jane began helping with the store as a teenager. Jane graduated from St. Andrew Priory, a private high school, in 1943 and went on to the University of Hawai`i, graduating in 1947. She married MIS veteran Toshio Komeiji the following year. After working as a program counselor for the university, she turned to teaching after having her own children, teaching at Ma`ema`e Elementary for over twenty years. With Dorothy Hazama, she wrote the book Okage Sama De: The Japanese in Hawai`i, first published in 1986, a book that graces the shelves of just about every Japanese American household on the islands. In the 1990s, she was a key figure in the early history of the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai`i, being part of the team that developed the core exhibition, also titled Okage Sama De.

Akiko Kato was born and raised in Seattle and sent with her family to Puyallup and Minidoka when war came. Graduating high school in Minidoka, she left to attend Friends University, a Quaker school in Kansas. After her 1948 graduation, she married Junelow “Junks” Kurose and, after a stint in Chicago, returned to Seattle. Back home, she was active in efforts to fight housing discrimination through the Congress of Racial Equality and American Friends Service Committee. When her six children were of school age, she enrolled them in Seattle’s Freedom School, where they learned about the Civil Rights Movement and race. Becoming interested in early childhood education, she began to teach in the 1970s and finished a master’s degree at age fifty-six. She was named Seattle’s Teacher of the Year in 1985 and received the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science and Mathematics in 1990. After her death of cancer in 1998, a middle school was named after her in 2000.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

Catch up on previous editions of Nisei Notables here.