October 16, 2024

At Densho, we field a lot of questions about where to find various resources related to the Japanese American incarceration online. While some things can be found via your favorite search engine, others defy a quick and easy search. This edition of Ask a Historian tackles some of the things we are asked about most often, as well as a few more you might not have known to ask about but are no less interesting.

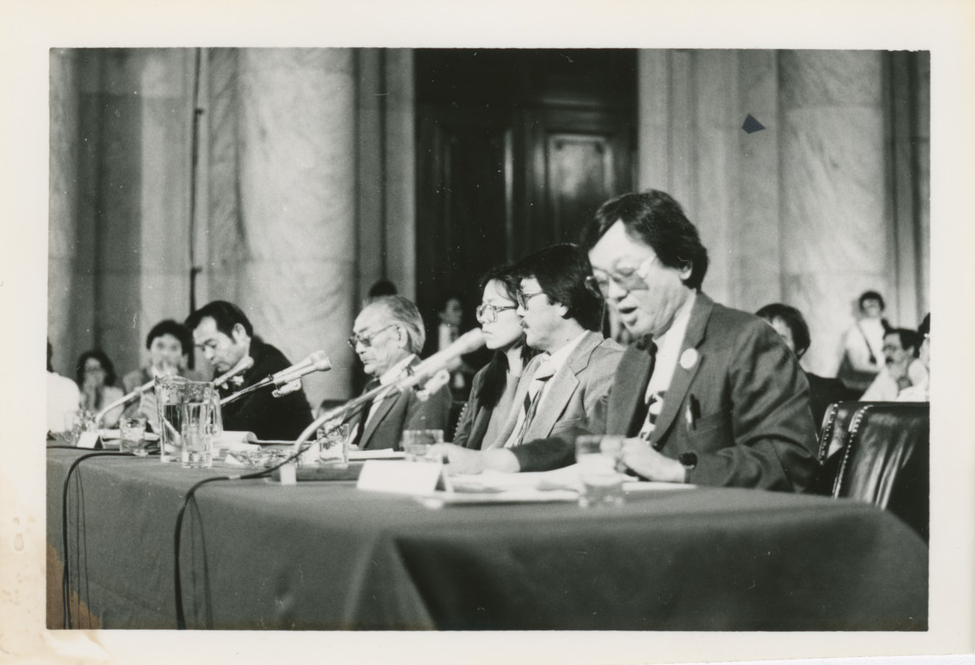

CWRIC Hearings on Redress

Though there was a fair amount of controversy about the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) at the time, scholars and community members alike now view the summer/fall 1981 hearings as a watershed moment for both the Redress Movement and for Japanese American historical memory. At these hearings—which took place in Washington, D.C.; Los Angeles; San Francisco; Seattle; Alaska; Chicago; New York; and Cambridge, Massachusetts—many Japanese Americans spoke of their wartime experiences for the first time. We also hear from key figures behind the forced removal policy, who range from relatively contrite to unrepentant.

The National Archives has recently made the full transcripts of the hearings available on their website.

Unfortunately, the hearings were not systematically filmed or videotaped, so there is not a full video record of the hearings. Visual Communications and NCRR (the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations, now Nikkei for Civil Rights & Redress) videotaped the Los Angeles hearings, and VC holds copies of the hearings in their archives. You can view highlights from the LA hearings prepared by the Japanese American National Museum for its 2017 exhibition Instructions to All Persons: Reflections on Executive Order 9066. A three-hour DVD with more extended highlights can be purchased from the Japanese American National Museum. The Chicago hearings were videotaped by students at Northeastern Illinois University, where the hearings were held, and have been made available online by the university. You can also view some highlights as part of a Chicago JACL program commemorating the 40th anniversary of the hearings. Densho has footage of the Seattle hearings and is in the process of digitizing it. The Downtown Community Television Center shot footage of the New York hearings; you view highlights in a 2021 video produced by the New York Japanese American Oral History Project. There is no known video of the other hearings.

Finally, the National Archives has also made available the report of the CWRIC, Personal Justice Denied. While it had been available on the National Park Service website, the NARA version is much easier to navigate. Though a bit outdated, given all that we have learned about the incarceration over the past forty years, it remains a useful summary even today.

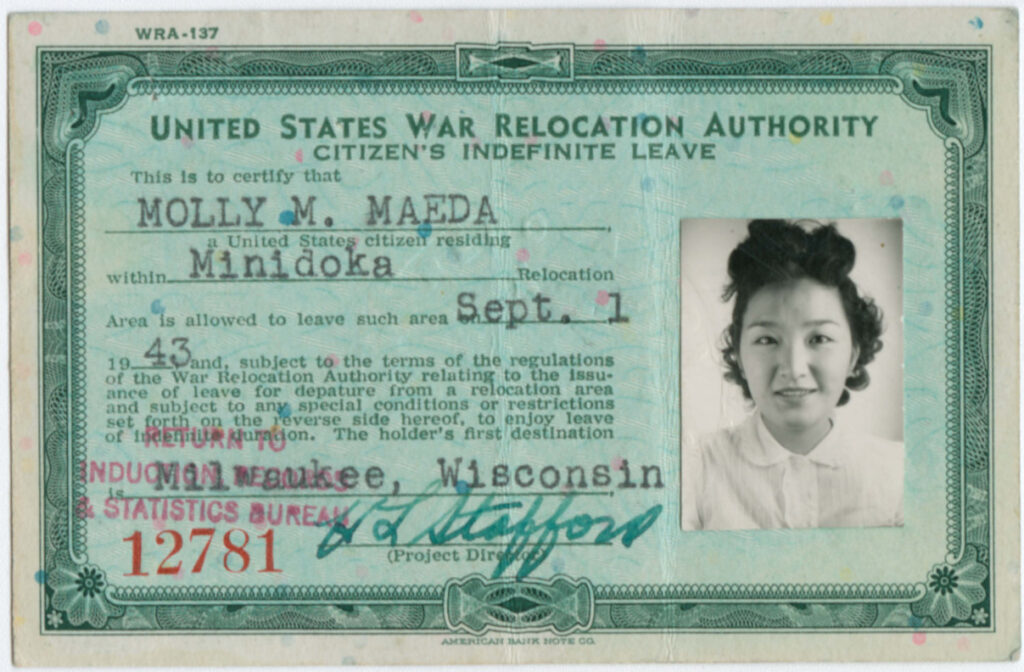

Camp Records

As most of you reading this will likely know, the War Relocation Authority—the federal agency that administered the concentration camps that held Japanese Americans forcibly removed from the West Coast during World War II—kept extensive records of its charges, much of which can now be accessed online. Densho’s Names Registry is one access point to these records, which are largely based on the Form WRA-26, the WRA’s entry census, and the Final Accountability Rosters, a summation of statistical records for each incarceree compiled after the closing of the camps. Rather than repeating what these are and how to use them, please use the links above to learn about the WRA records as well as this link to learn how to use our Names Registry. A couple of years back, we also partnered with genealogist Linda Harms Okazaki on a webinar series that you can access here. Session 5 specifically focused on camp records. You can also download the WRA official statistical summary, titled The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Description, which provided detailed numbers of various aspects of the WRA’s program.

Unfortunately, records of the agencies that administered the various other detention sites that held Japanese Americans are much less accessible. The records of the Wartime Civil Control Administration, which ran the so-called “assembly centers,” are largely unavailable online, though I am told that the National Archives are in the process of digitizing at least some of these records. Similarly, records of the army or Justice Department-run internment camps are mostly not accessible online.

There has however, been a significant development on this last front, as the National Archives has recently made Japanese American Internee Cards available online. These index cards list the detention histories of many of the Issei held in the army or Justice Department camps. I’ve poked around this collection just a little bit and have found widely varying amounts of information for different internees. For my grandfather, Shoichi Asami, there is just the front and back of a single card that doesn’t include all of the sites at which he was held. By contrast, there are eighteen images of cards pertaining to George Kumemaro Uno, the Uno Family patriarch and father of famed Nisei Buddy, Amy, Edison, along with seven others. I don’t know if there are cards for all internees, but I found at least one card for everyone I looked for.

Finally, there is the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai`i’s Hawai`i Internee Database, put together and maintained by their exemplary volunteers. In my grandfather’s case, there is more complete information on his internment journey, as well as photos, a family tree, and the story of his tragic end.

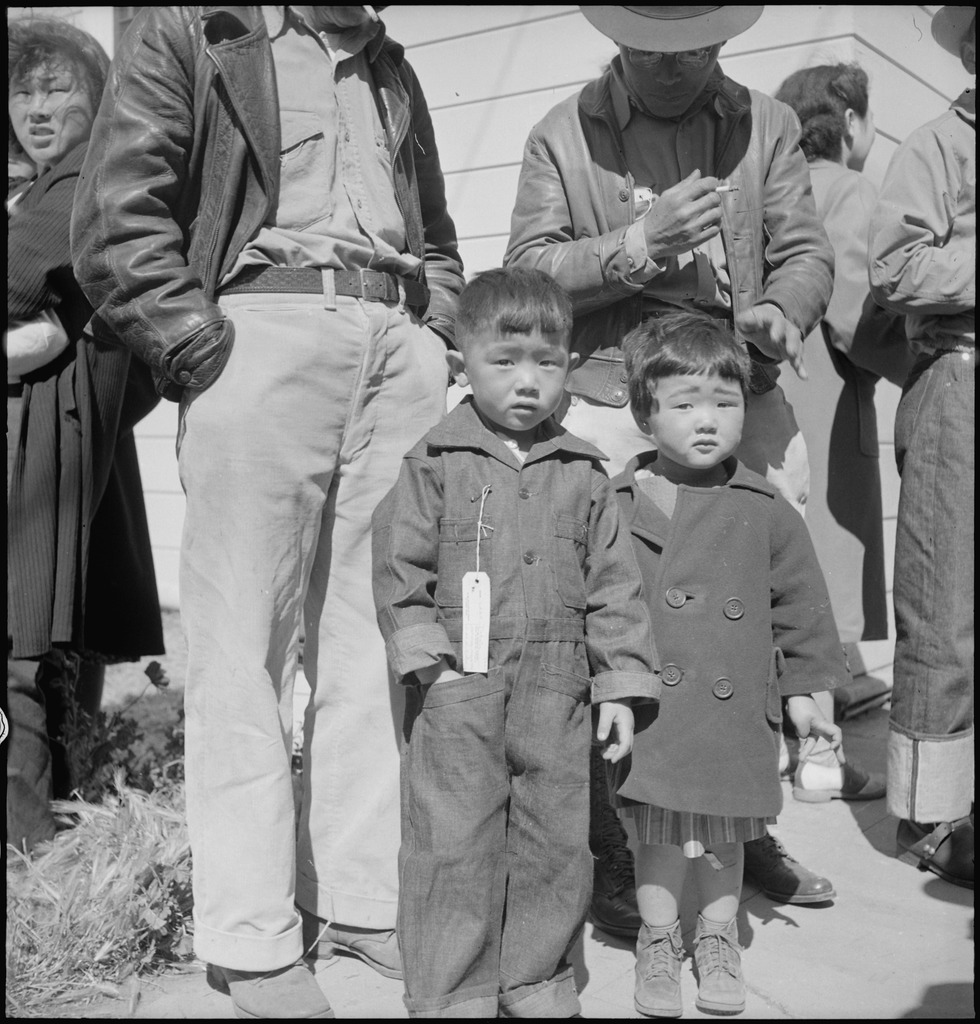

WRA Photos

Though Densho and others have made large numbers of photographs taken by Japanese Americans available, the photographs taken by the War Relocation Authority’s Photographic Section (WRAPS) remain the most commonly used source of visuals of the roundup, incarceration, and aftermath. As the late Lane Ryo Hirabayashi wrote in his Densho Encyclopedia article on WRAPS, the photographs remain useful even given their propagandistic origins and can be recontextualized by contemporary users.

Beyond the handful of WRAPS photos that are in Densho’s collection, there are two large caches of such photos online. The National Archives has digitized around 4,000 WRA photographs. Just out of curiosity, I searched for the various WRA photographers and this is what came up:

- Francis L. Stewart: 1,002

- Dorothea Lange: 878

- Thomas W. Parker: 749

- Clem Albers: 382

- Hikaru Iwasaki: 296

- Charles E. Mace: 93

- Gretchen Van Tassel: 18

The cache also includes some images by WRA reports officers (whom I’ll be writing more about at a later date) from Jerome, Tule Lake, and Amache.

The Bancroft Library collection includes about 7,000 WRA images. Note, however, that many of the photographs are scanned on both the front and back, so the actual number of photographs is significantly less than 7,000. You can also browse the finding aid for this collection.

A search for photographers yields a somewhat different distribution:

- Hikaru Iwasaki: 1,318

- Francis L. Stewart: 1,087

- Thomas W. Parker: 938

- Charles E. Mace: 795

- Dorothea Lange: 632

- Clem Albers: 334

- Gretchen Van Tassel: 208

There are many more images from Iwasaki—who mostly photographed resettlement—and fewer from Lange, among other differences. As with the NARA set, there are also a handful from reports officers, again with a slightly different distribution, as well as a few additional camps and photographers. There are also a good number of photographs that have no photographer credited.

The bottom line here is that, while there is undoubtedly a good deal of overlap between the NARA and Bancroft collections, one should search both of them, since there seems to be a good number of images unique to each.

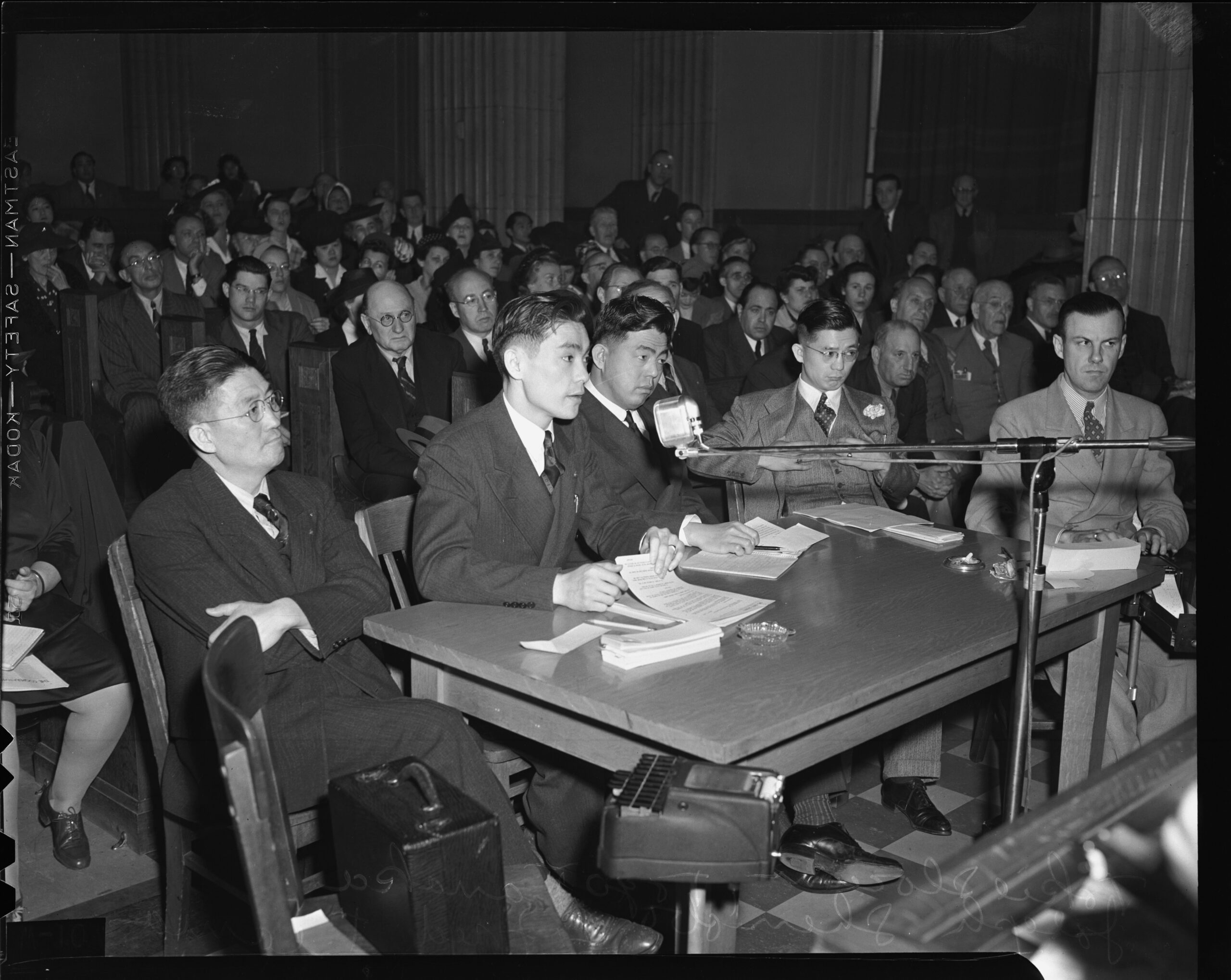

Tolan Committee Hearings

Finally, here are some links to transcripts of the House Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration from February and March 1942, commonly known as the “Tolan Committee.” These hearings on the possible exclusion of Japanese Americans took place as plans for that exclusion were already underway, so they had no impact on the actual decision. They remain interesting as a window into public opinion—including those of a fair number of Japanese Americans—at that time.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

Read answers to previous questions submitted to our recurring Ask a Historian series here. Have a question of your own? Send it to info@densho.org.

Make a gift to Densho to support the Catalyst!

[Header: Japanese Americans lined up outside a mess hall in Manzanar, May 1942. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]