June 30, 2023

Densho Archives Intern Ron Martin-Dent shares some lessons learned and surprises uncovered during his time adding new collections to the Densho Digital Repository.

I first learned about the incarceration of Japanese Americans through my college history classes. I was shocked to learn that Japanese American families had been ordered to leave their homes along the West Coast and that places familiar to me like the Puyallup fairgrounds and Fort Missoula had been used as detention facilities during the war. These are stories that I firmly believe that more people need to hear, and it’s been an honor to help make the letters, photographs, photo albums, pamphlets, and other materials I’ve been working with this past year more accessible to a wider audience.

Making Connections

I have two personal connections to Densho’s mission. Before starting graduate school for library science, I worked at a publishing company. One of the books I worked on that left a strong impact on me was a poetry collection by an author whose family had been incarcerated at the Topaz concentration camp. My experiences working on that book inspired me to apply for this internship, which seemed like a fantastic way to explore working in a community archive while continuing to do the thing I loved most about publishing: helping people’s voices be heard.

I also have a family connection to Densho’s mission, which I did not learn about until after I started my internship. My aunt told me last fall that one of her relatives by marriage was incarcerated at Tule Lake during the war and that his neighbors looked after his family’s home and farm while they were incarcerated. I’m eager to learn more about this history, especially now that I’ve gained more context through my work at Densho.

Connections have been a running theme throughout my internship at Densho. I’ve worked on four collections this year, which have varied in size, scope, and contents, but there have been some surprising connections I’ve uncovered along the way.

We sometimes find duplicate copies of published works, multiple prints of a single photo negative, and photographs of the same people taken years apart. These multiples—and the subtle differences between them—can provide important clues about the object’s history and the lives of the people who owned them. They can also shine a spotlight on some of the trickier parts of the work we do as archivists.

The Kenji Ima collection, which I’m currently processing, has a lot of photographs and photo albums, but not all of the photographs have labels. It’s been an interesting bit of detective work to figure out who the people are in some of these photos, and sometimes I’ll process dozens of images before I find a photograph with the clue that answers the question “who is this?”

Here’s an example to show what I mean:

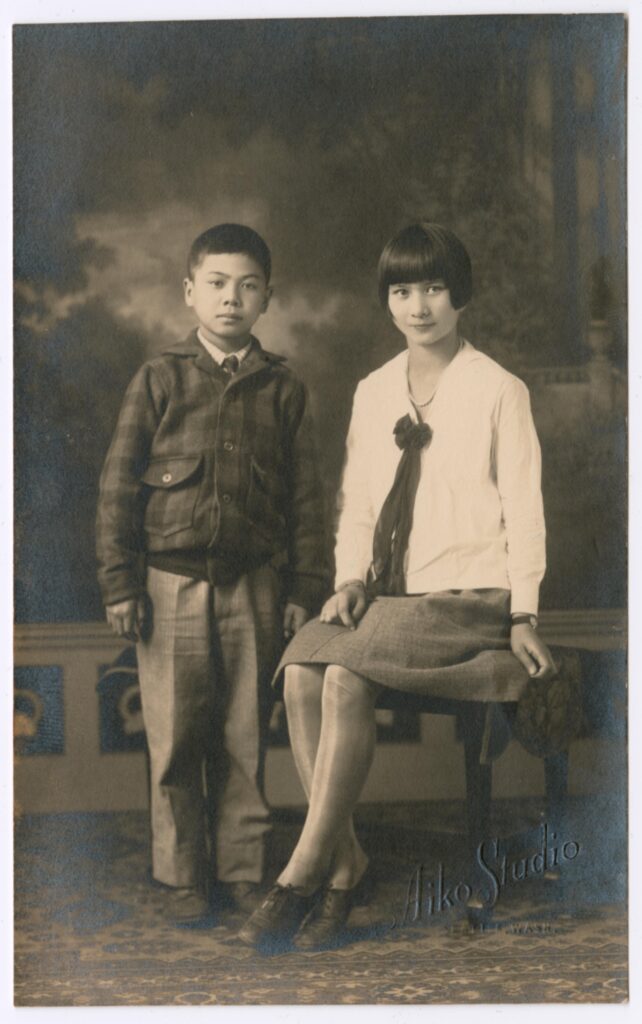

This is a photo postcard of siblings Mary (Fukuyama) Ima and Tsutomu “Tom” Fukuyama taken in October 1927. They’re identified on the back of the postcard where someone has written their names in cursive.

Here’s another photo of the siblings from a few years earlier:

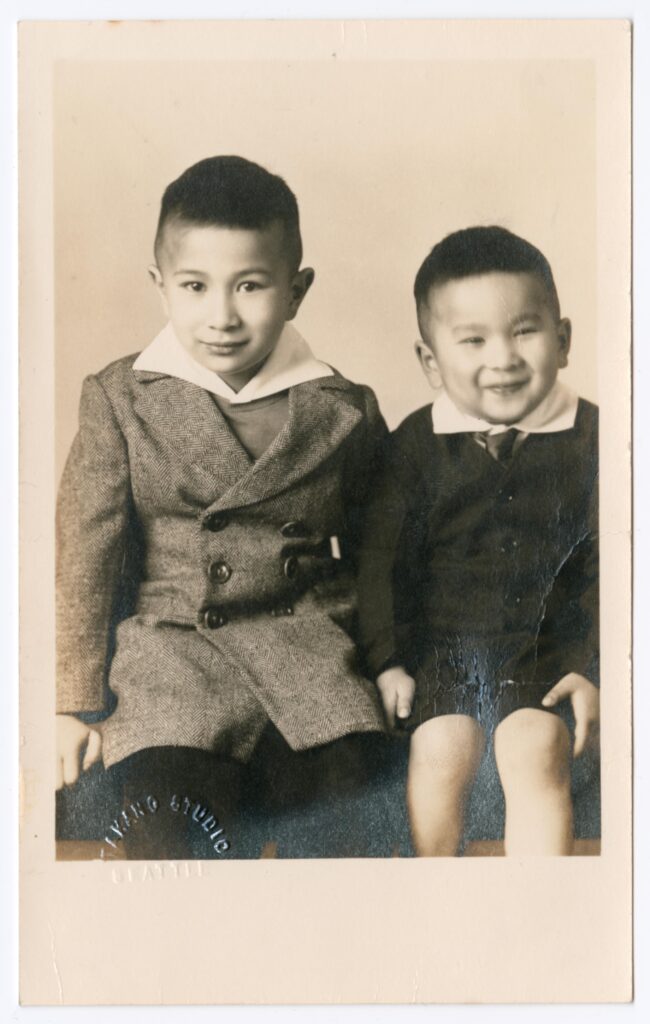

This photo is from an album I processed a couple hundred objects later in the collection. Only this time, the photo wasn’t labeled. There was no information in the album that told me who these children were or when the photo was taken. While I was working in Photoshop, I thought, “this photo looks familiar,” so I went back through the rest of the collection looking for a similar photo. The Kenji Ima collection has quite a few duplicate and near-duplicate photos—shots taken from alternate angles, prints using a different photo development process, stuff like that—so I thought I might find a clue somewhere. Sure enough, here were the same two kids, a few years apart.

I double-checked my detective work by looking for other labeled photos of Mary and Tsutomu.

This process involves a lot of deductive reasoning and a little bit of guesswork. Sometimes, the critical clue will be a signature outfit that a person wore throughout their lifetime. Other times, the only clue we’ll have to go on is a person’s facial features.

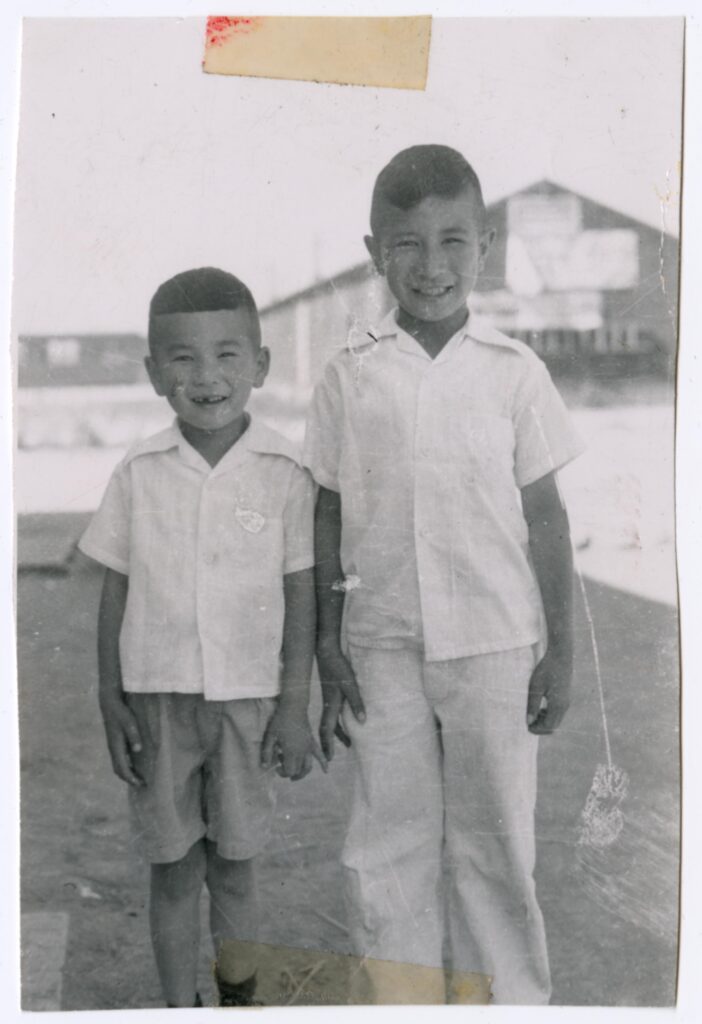

Here’s an example showing Paul and Kenji Ima at different ages:

Some of these photos were labeled, others were not. My job is to correctly identify these boys whenever I see them in a photo.

It’s not a foolproof process, so if you ever come across a photo in the DDR and think, “Hey! That’s not the right person identified in that photo,” I hope you’ll have a bit of mercy on us interns and send a polite correction to the archives team.

Some Advice for the Family History Keeper

One way that you can help archivists out is by labeling your family photos. The American Library Association and the American Institute for Conservation recommend using an ordinary #2 pencil to lightly write the person’s name on the back of the photograph (pro tip: use cotton gloves whenever you’re handling photographs to help the print last longer), but you can also use a special smudge-free permanent archival-quality pen like a Pigma pen if you’re feeling fancy. Another easy way to label photos is to write the names on a piece of acid-free paper (the kind scrapbookers and artists use) and store that alongside the photo for reference.

It can be a little tricker to label digital photos, but luckily there are tools in programs like Apple Photos, Microsoft Photos, Facebook, Instagram, and other online photo storage solutions to tag people in your photographs. You can also find more tips for preserving your family collections from the Densho Archives Team here!

There’s a double advantage of labeling your photos: when it comes time to pass your treasures down to the next generation, your kids and grandkids will be grateful to have the names written down for all the people they don’t recognize in these old family photos. Believe me, I’ve been asking my parents to label all their photos ever since I started this internship. I’ve been looking at the spare copy of their wedding album that they gave me and wondering who all of these people are. Unfortunately, my dad’s been wondering the exact same thing. That’ll be another challenge for us to figure out down the road.

—

By Ron Martin-Dent, Densho Archives Intern

Ron Martin-Dent (he/him) is a graduate student in the University of Washington’s Master of Library and Information Studies program. Prior to grad school, he worked for five years as a production editor at a nonprofit literary press. He graduated from Pacific Lutheran University with a B.A. in English Literature and from Green River College with an A.A. in History. Ron hopes he can help others discover their own connections to the past so we can create a more equitable future together.

Funding for this internship was generously provided by the Washington State Historical Society’s Diversity in Local History Program.