December 14, 2022

Densho’s new executive director Naomi Ostwald Kawamura brings with her a deep knowledge and passion about public education’s role in ensuring that the stories of Japanese American WWII incarceration reach future generations. Naomi spoke with Densho Media & Outreach Manager Nina Wallace about how her family history sparked a lifelong interest in education and public service. Their conversation delved into the power of intergenerational memory in shaping identity and community, and why the stories we tell about our past matter today. Read their (abridged and lightly edited) conversation below.

Nina Wallace: Let’s start out with some personal background. Your family wasn’t incarcerated during WWII, so you kind of have a different Japanese American experience. Can you share a little bit of your family history?

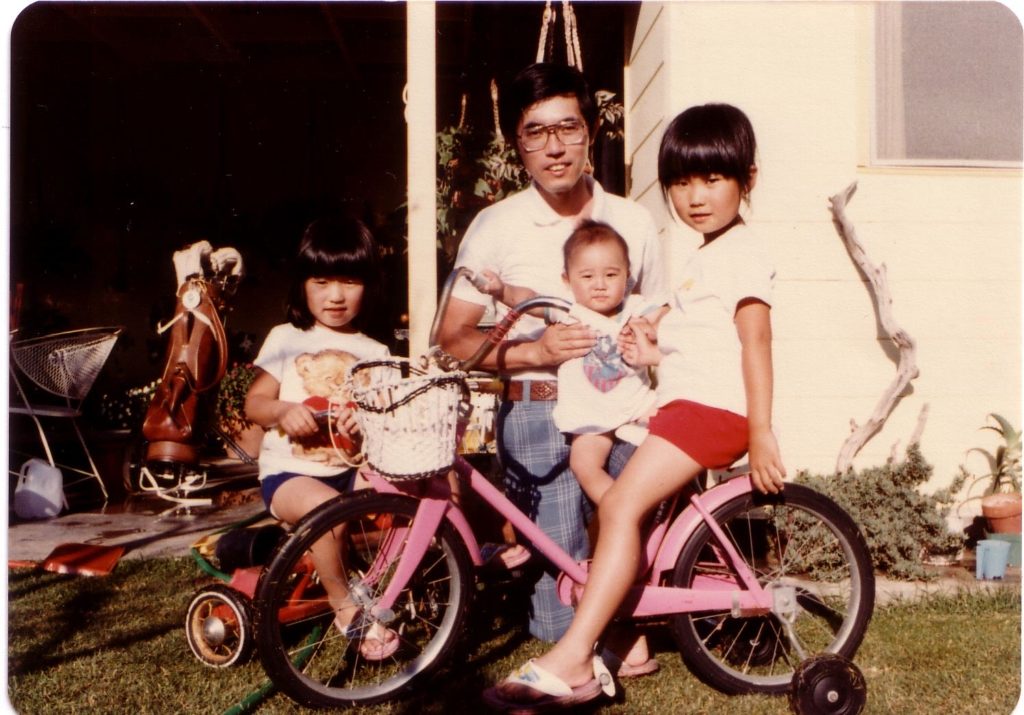

Naomi Ostwald Kawamura: My parents are both Japanese citizens who immigrated in the early ‘70s to California, then lived overseas in Europe and Latin America before returning to the US for their retirement. They’ve actually both now lived longer overseas than they’ve ever lived in Japan. They both wanted to see the world, so they’re a little bit unusual people in the sense that they were very curious about seeing other parts of the world together.

I always think about how they didn’t speak English very well and came during a time when there were no Google Maps and no cell phones. They figured it out and established a life for themselves in San Diego. My parents are very resilient people. They don’t fall into the typical tropes of Asian parents in the sense that they weren’t pushing hard on me around my academics. I became an overachiever for some other reason, but not because of them.

NW: It was for yourself. [Laughs]

NOK: I like the stress and anxiety! I really thrive on it.

NW: So what were your family’s experiences during the war?

NOK: My mom is younger, so she has a post-war beginning to her life. My dad was born in Hiroshima, just a couple kilometers from the epicenter. His mom had passed away during the war already, and so he and his dad were together. He was being cared for near a hillside that actually was what shielded him from the blast. Even though he was so close to the center, it seemed like everybody that lived on this one part of the hillside survived. My grandfather was at work. He worked for the railway and survived because he happened to drop his cigarette under his desk during the moment of the blast. That shielded him because he was underneath a steel desk trying to find his cigarette.

And so their experience was a lot of trying to understand what had happened. My dad, his whole childhood, early childhood, are memories of being undernourished, trying to learn American English words and chasing after American soldiers for — chocolate was one of his first words and so he has memories of running after American soldiers for food. He was malnourished for most of his young childhood and had friends and classmates who slowly just disappeared, you know? They passed away from the effects of the bombing. And he remembers the story of the 1,000 paper cranes because he remembers that he and his classmates made cranes for her as a childhood memory.

NW: For Sadako Sasaki? [Sasaki was a young girl who survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima but later developed leukemia from the radiation poisoning. While in the hospital, she began folding origami cranes, inspired by a Japanese saying that if you fold 1,000 cranes your wish will be granted, with the wish that she would live. She died at age twelve.]

NOK: Yeah, he remembers her and remembers making cranes for her. He has lots of interesting, very distinct memories that are so traumatic for a child to go through. I think it’s so amazing because he’s somebody that has so much gratitude towards life and beauty and is actually more of a light-hearted person than someone that’s dark. He really has committed so much of his current chapter of his life on talking about his wartime experiences or talking about how he’s had this chance to live around the world and making friends with people who have different kinds of backgrounds and cultures. That’s one pathway towards peace is to understand and learn about other people that approach life differently than you. And he also gets a lot of invitations for oral histories and gives talks at high schools. He has a busy retired schedule because he’s gotten so involved in more of these peace efforts.

NW: Did your dad talk about all of this when you were growing up or is it something that he came to in later years?

NOK: Yeah, so very, very similar to the Japanese American experience where there was silence, the “Okay, find work, go to school, try to build a life for yourself.” And then at some later point he started talking about his experiences, really when I was a teenager and I realized, “Oh my God, he was there.”

We went to the Hiroshima Memorial Museum together. And when I went through that museum at that time, I realized what a gift that my dad survived. What a gift that my grandfather survived. That’s something that I didn’t really understand until I was a little bit older.

So then I really got interested in memory — interested in what I should do with a memory I didn’t experience but feel very attached to it and feel some responsibility to it. I felt this obligation to make something with my life because my grandfather and my dad survived something that I felt…it seemed so wasteful if I just sort of frittered away my life and didn’t do anything that contributed to society or find a way to be in service of people. That definitely has defined who I am. My life trajectory is so much about how that history has impacted me.

NW: So it sounds like a lot of your interest in public history and education very much comes from your family.

NOK: One hundred percent. Because I’m actually not someone that loved history as a subject in school. Actually, I hated history as a subject. I’m not someone that retains and remembers very specific dates and chronologies. And so I describe myself as more of a cultural memory scholar. I’m interested in memory studies because it’s more about how people make use of the past to make sense of the past and their daily life. It’s more about, how does memory shape who you are? How does that shape how you identify as part of a certain community or not? How has that informed your motivations, the kind of career paths you choose, and things like that. So I’m really interested in the past but in a very kind of particular way. And from that, then there’s crossover into history, education, and public history because it is also about usefulness — how do we teach history in a way that’s useful to young people?

NW: You’re a doctoral candidate at the University of British Columbia, finishing up a dissertation on the intergenerational transfer of memory in Japanese American and Japanese Canadian communities, which you describe as “memory work.” That’s a term I hadn’t heard before, but it feels so poetic and fitting. What does memory work mean to you? Is there anything you learned along the way that surprised you or changed how you think about this work?

NOK: The premise that I now operate on is that we construct stories. Human beings are natural storytellers. We tell stories to make sense of events that have happened to us. We make stories about our lives, so that our life has more meaning. And so stories are really essential and core to who we are and how we operate and how we can have a more meaningful life. And so that’s something that I’ve come to really deeply understand since I’ve started my doctoral journey, is the importance of thinking about how narratives and stories are such a human activity and that it’s so important to people. And that’s why certain memories, certain family stories, certain histories are so important to people, is that they give your life meaning if you know that you’re part of a bigger story.

And that’s why I’m interested in communities and how we construct stories about who we are — but that we actually have to keep changing and adapting those stories. They’re not static. And so I think that’s something that is a newer understanding about identity is that — like, a JA community identity is not static. It’s not something that could be constructed in 1960 and stays the same, or in 1980 and stays the same, and then in 2000 it’s the same. People have to actually be pushing on the edges of it and engaging in dialogue with each other.

I think it’s really powerful to feel like you’re a part of another group, beyond your own family, that you also are part of another history and story that you’re contributing to, and hopefully your life contribution then adds to that group’s story about themselves. It’s something that I also think is powerful.

NW: Well, this has been fascinating to hear a little more about your family history and the path that led you here. I’m excited to keep these conversations going as you dig deeper into your work at Densho!

–

This is the first in a series of interviews we’ll be publishing with Densho’s new director, Naomi Ostwald Kawamura. If you have questions you’d like us to consider including in a future interview, please email them to media@densho.org.