June 1, 2022

Yoshito “Yosh” Kuromiya is best known as one of the sixty-three men from Heart Mountain convicted in 1944 for refusing to report for induction in the largest mass trial in Wyoming history. Later in life, Kuromiya became one of the most outspoken of the Nisei draft resisters and a key figure in the revival of their story in the 1990s and beyond. The posthumous publication of his memoir represents the first and only memoir by any of the Nisei draft resisters and greatly adds to our understanding of his own thoughts on his actions and on the draft resistance movement in general. Beyond the politics of resistance, the memoir is also an insightful portrait of a Nisei artisan.

Beyond the Betrayal: The Memoir of a World War II Japanese American Draft Resister of Conscience tells Kuromiya’s story in a pretty strictly chronological manner. The story begins with a lengthy first chapter that covers years before Yosh’s 1923 birth, mostly written from the perspective of his Issei mother, Hana Tada Kuromiya, who married his father, Hisamatsu Kuromiya, in 1916 when the latter returned to his home village in Okayama prefecture after having been the in US for a decade. Written in a novelistic style, the chapter covers the young couple’s early years in the US, a successful business venture broken up when Hisamatsu discovers that one of his partners had been embezzling from the company, and the birth of four Nisei children, of which Yosh is the third. A brief note indicates that that chapter is based on Hana’s stories, with Yosh “filling in the gaps with my own imagination.” As such, this should probably be read more as family folklore than as fact. But Kuromiya proves to be a colorful and creative storyteller, and this account of his family is enjoyable to read.

Subsequent chapters switch to a more conventional first-person style. Relative to other Nisei memoirs, chapters on his childhood, the coming of World War II, and wartime incarceration (in Kuromiya’s case, at the Pomona Assembly Center and Heart Mountain) are disappointingly brief. Though there are interesting stories of his childhood in Pasadena and Monrovia, California (areas east of downtown Los Angeles), and of his parents’ successful retail produce business, Kuromiya pretty much skips over the later 1930s, so we learn little about his coming-of-age, politics, education, or views of Japan and international developments, which might have provided insight into his later politicization as a draft resister. The chapters on life in Pomona and Heart Mountain also feel a bit perfunctory, as if anxious to cut to the draft resistance chase.

The heart of the book lies in the chapters covering the draft resistance movement at Heart Mountain, the subsequent group trial, and his later imprisonment at the McNeil Island penitentiary. There have been other shorter first-person written accounts of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee and its precursor the Heart Mountain Congress of American Citizens by Frank Inouye and Frank Emi; an outstanding academic monograph (Eric Muller’s Free to Die for Their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II ); a documentary film (Frank Abe’s Conscience and the Constitution, 2000); and numerous oral histories (many, including one of Kuromiya himself, in Densho’s collection). But Kuromiya’s more detailed account adds much to our understanding of the story. Though he is not particularly reflective in detailing the reasons for taking his stand or on how that made him feel, he is frank in noting his family’s mostly disapproving reaction, getting dumped by his girlfriend, and his own mixed feelings toward the leaders of the draft resistance movement. The chapters on his confinement at McNeil Island are particularly insightful.

Also insightful are the early postwar chapters, as Kuromiya writes in detail about the overcrowding and general hardships the family faced upon return from camp/prison, which is a valuable addition to the literature on the immediate postwar period. Initially becoming one of the many Nikkei men to become gardeners, Kuromiya begins to take night classes at Pasadena City College to study landscape design, where he is mentored by a member of the Native Sons of the Golden West, an organization that had been notorious for its anti-Japanese stance before and during the war. He eventually becomes a successful landscape architect, working for prominent local firms, before going out on his own. He also marries and starts a family that consists of four daughters, though that marriage later breaks up. Kuromiya has interesting things to say about the conflict between artistic vision and commercial prospects that drive key decisions in his career. (For readers interested in more on early postwar Pasadena, see our recent webinar “Untold Stories of Post-Camp Pasadena,” at which one of the presenters, Naomi Hirahara, mentions Kuromiya in a larger discussion of Japanese American gardeners.)

The final chapters detail the growing interest in the story of the draft resisters that began in the 1980s and Kuromiya’s own efforts in the 1990s and beyond to tell their story as younger Japanese Americans begin to embrace them.

The memoir is a fairly brief one—just 145 pages including many photographs and images of Kuromiya’s art—so there is a fair amount of additional material added to bring the manuscript up to book length. Other contributions include insightful introductory materials by Eric Muller and editor Art Hansen, a lengthy poem about/for Kuromiya by the esteemed poet Lawson Fusao Inada, and four separate appendices.

For the ever prolific Hansen, this is his third resistance-focused book to come out in the past few years, following his anthology work Barbed Voices: Oral History, Resistance, and the World War II Japanese American Social Disaster and his editing of James Omura’s memoir Nisei Naysayer: The Memoir of Militant Japanese American Journalist Jimmie Omura. Relative to the latter, the current volume has many fewer annotations and footnotes, perhaps at the behest of the respective publishers. As one who enjoys reading all of them, I think it could actually have used a few more—when, for instance, Kuromiya recalls entering Heart Mountain in August 1942 to a camp “encircled by a barbed wire fence” (Heart Mountain was one of the WRA camps at which the fence did not go up until weeks after inmates had arrived, with the fence construction project leading to much inmate unrest) or when he mentions the reuniting of Issei internees with their families at Tule Lake or Crystal City (most such reunions actually took place when internees were “paroled” to “assembly centers” or WRA camps). But what annotations there are—including some authored by Muller and many that cite Densho—are useful and appropriate.

While perhaps not the book for someone looking for a typical inmate’s perspective on Japanese American incarceration and life in a concentration camp (see this list for some I recommend), Beyond the Betrayal is a valuable addition to the literature of Japanese American resistance that is also an illuminating portrait of a Nisei artisan building a career in postwar Southern California. I highly recommend it for readers interested in these topics.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

Learn more about Beyond the Betrayal: The Memoir of a World War II Japanese American Draft Resister of Conscience by Yoshito Kuromiya, ed. Art Hansen, here.

Hansen will discuss the book with Lawson Iwao Funada and Kuromiya’s family at an event hosted by the Japanese American National Museum on June 4. Learn more and RSVP.

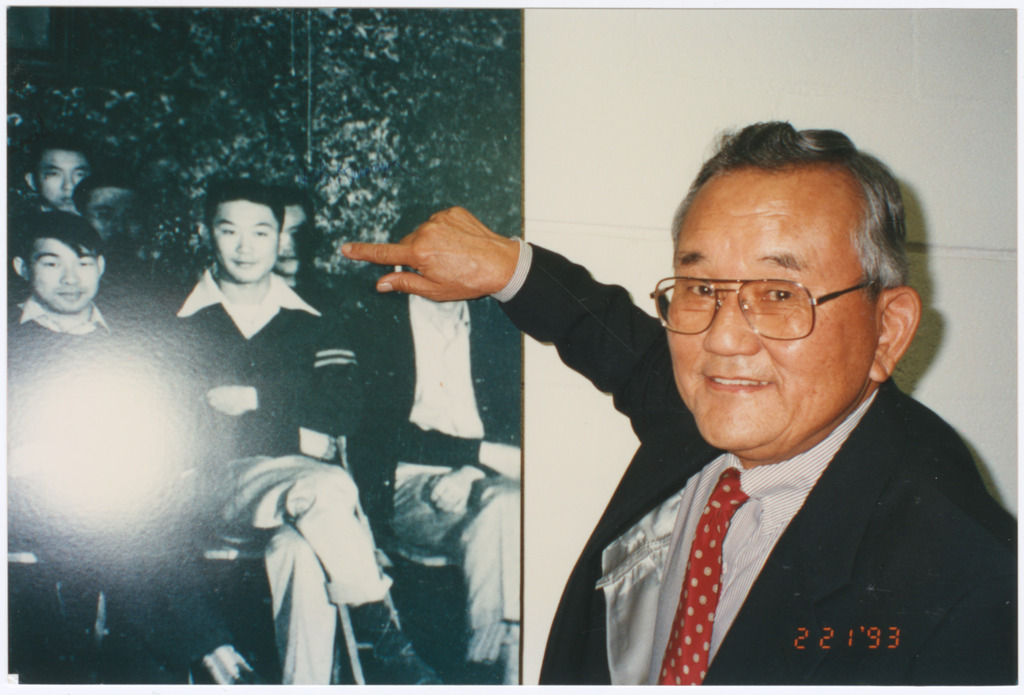

[Header: Photo of Kuromiya in barracks for use with “Conscience and the Constitution” documentary, c. 2000. Courtesy of Frank Abe.]