April 29, 2022

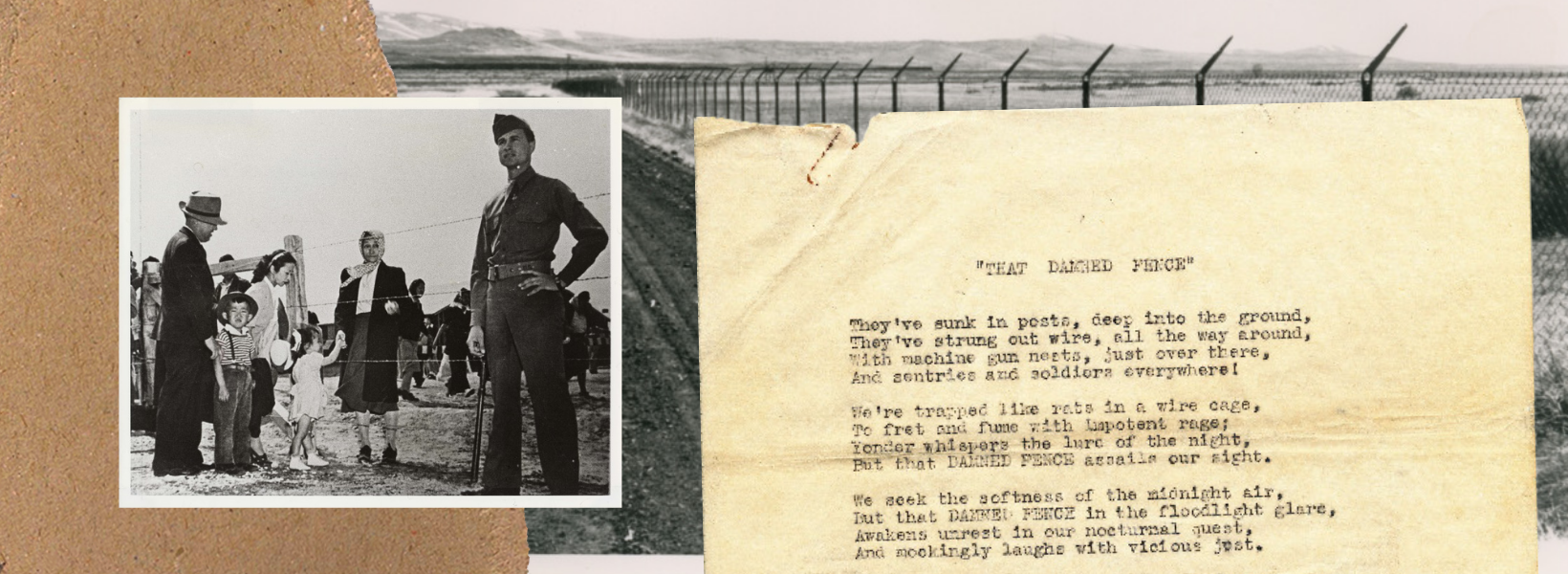

The barbed wire fence is an enduring symbol of the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans. As Hana and Noah Maruyama point out in Episode Three of the Campu podcast, the fences, watchtowers, and sentries with their guns pointing in inspired much anger and resentment among the captive population in these American concentration camps. “That Damned Fence,” a poem passed anonymously from inmate to inmate and camp to camp, put those feelings on paper. But who actually wrote the poem remains a mystery that we may never solve.

“THAT DAMNED FENCE”

They’ve sunk in posts, deep into the ground,

They’ve strung out wire, all the way around,

With machine gun nests, just over there,

And sentries and soldiers everywhere.

We’re trapped like rats in a wire cage,

To fret and fume with impotent rage;

Yonder whispers the life of the night,

But that DAMNED FENCE assails our sight.

— excerpt from one version of “That Damned Fence”

Perhaps the most prominent attributions for the poem are famed resister Minoru “Min” Yasui and Jim Yoshihara — although “author unknown” is common as well. One source of this confusion appears to be, well, Densho.

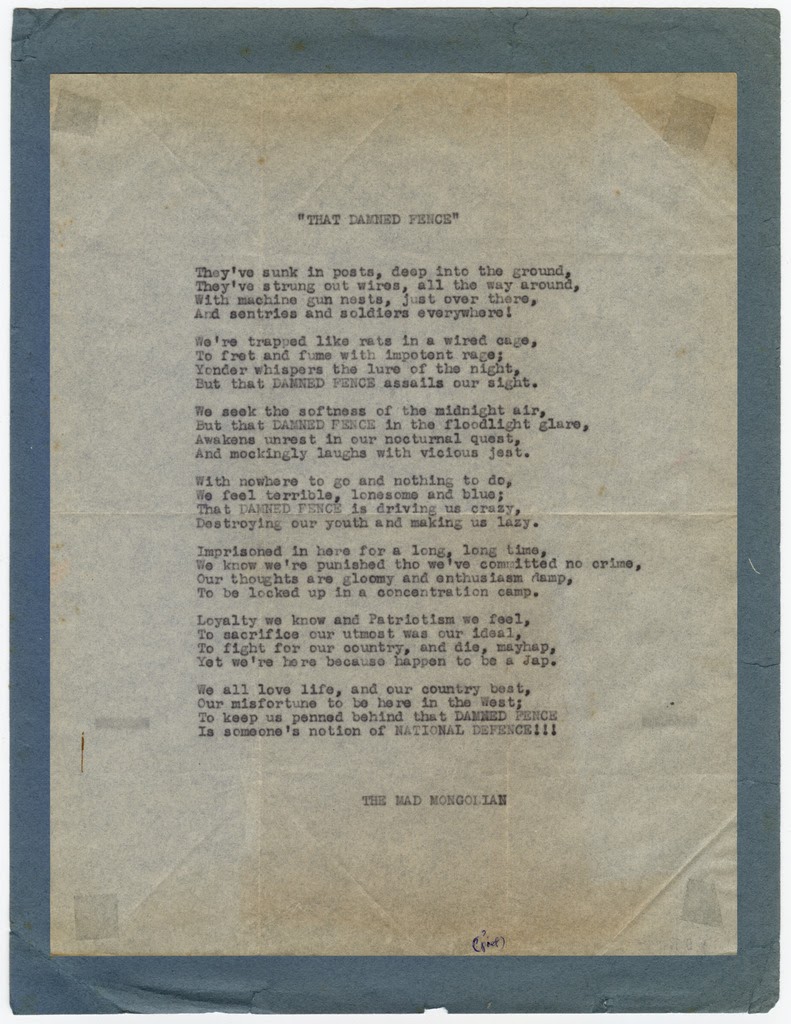

There are no less than four separate copies of “That Damned Fence” in our archives, each of them attributed to a different author and bearing some subtle variations. The first, donated as part of the Yoshihara Collection, is described as being written by a Jim Yoshihara “while incarcerated at Minidoka.” The others are more recent additions to the Densho Digital Repository: An “anonymous poem written in camp” from the Frank Abe Collection, a copy signed by “the mad Mongolian” from the Yuriko Domoto Tsukada Collection, and one signed by Min Yasui himself from the Min Yasui Collection.

A display featuring an excerpt from “That Damned Fence” at the Minidoka National Historic Site also credits the poem to Yoshihara, but it’s likely that this attribution is based on the one in Densho’s archives, since the other three versions weren’t published on our site until 2020. The display seems to have helped solidify Jim Yoshihara as the author for many visitors to the site over the years — though the folks at Minidoka say to expect an updated display coming soon.

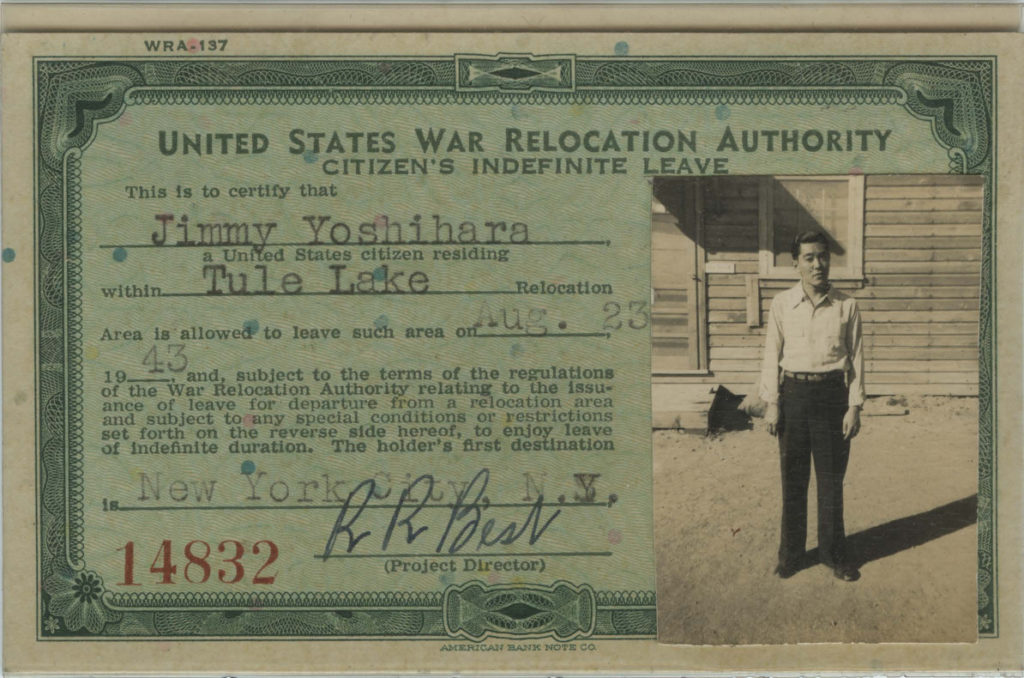

Upon further investigation, there doesn’t appear to be any historical record of a Jim Yoshihara at Minidoka. According to the government’s entry and exit data from the camps, there was no “Jim” Yoshihara in any of the ten War Relocation Authority concentration camps. A James Yoshihara was incarcerated at Jerome but, at just eight years old in 1942, seems an unlikely author. The Yoshihara Collection does contain a citizen’s indefinite leave card for “Jimmy” Yoshihara, but Jimmy and his family were incarcerated at Tule Lake, not Minidoka. Since the Yoshiharas lived in Shelton, Washington before the war, it’s possible that the donor of the collection simply thought they were sent to Minidoka along with families from the Seattle area. At any rate, it’s still possible that Jimmy Yoshihara wrote the poem, just not in Minidoka.

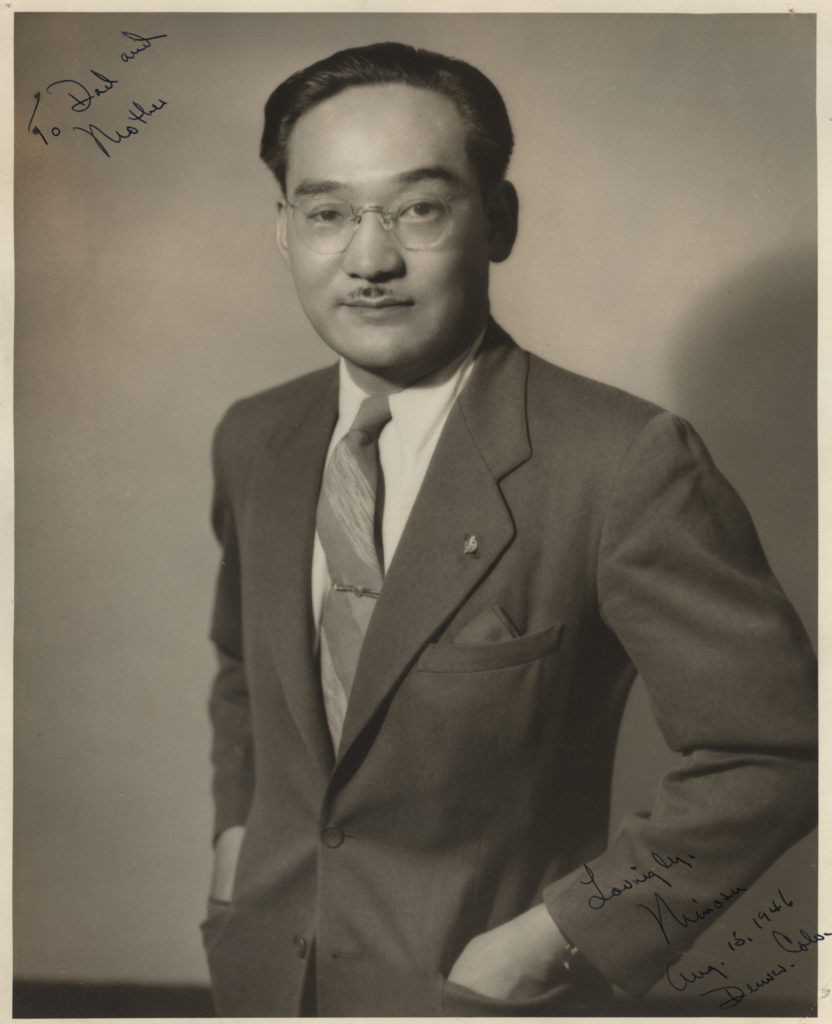

Min Yasui’s claim to authorship makes a different case. Having been sentenced to a year of solitary confinement and allowed no exercise periods, showers, or haircuts, he composed a handful of prison poems to fill the time. There is certainly an argument to be made that “That Damned Fence” is similar in both style and substance to these other poems — which he’d later sarcastically describe to his daughter Holly as “doggerel.”

Yasui maintained an active correspondence with his youngest sister Yuka throughout his imprisonment at the Multnomah County Jail, sending her letters and poems in Minidoka. One of these letters included a copy of “That Damned Fence” with a typed signature line naming Min as the author — a document that Yuka kept for over 50 years, and possibly the same one that is now digitized in the Yasui Collection. For the Yasui family, this document, along with the “mad Mongolian” signature on other copies — more on that in a moment — points to Min Yasui as the most likely author.

But there are still a few unanswered questions in this version of the story. For one, the timing of Yasui’s imprisonment doesn’t neatly align with the poem’s contents or when it began spreading throughout the camps. Japanese Evacuation and Resettlement Study researcher Charles Kikuchi notes in a March 24, 1943 diary entry that the “interesting poem” was posted on a bulletin board in Gila River in December 1942. He writes that the author is unknown, and that the poem “might have been written by somebody from the other centers and then passed around as such things are in times like this.” A reference in Paul Bailey’s City in the Sun, sourced from the WRA archives at the Library of the University of Arizona, describes the poem “written by some unnamed Nisei” being “freely circulated, read at the fire circles, and posted on the block bulletin boards” in Poston during the same time period.

In December 1942, Yasui was in the Multnomah County Jail, not Minidoka or any other camp. After being arrested for defying curfew on March 28, 1942 and released on bail, Yasui had spent that summer detained at the Portland Assembly Center before being transferred to Minidoka along with his fellow incarcerees in early September. He was brought back to Portland for the verdict on his trial on November 14, when he was found guilty and sent to Multnomah for his act of civil disobedience. So while Yasui did indeed see and experience Minidoka firsthand, at the time the poem began to circulate he was no longer there.

Additionally, there was no fence at Minidoka when Yasui and most other inmates arrived at the camp. Construction of the fence didn’t begin until November 6, 1942, three months after the camp opened and a little over a week before Yasui was summoned back to court. Yasui would have witnessed some of the subsequent unrest, but was still in the Multnomah jail by the time it was completed. It’s unclear how well-informed he would have been on events in Minidoka after leaving the camp, though there is always the possibility that his description of the fence was based on second-hand reports from Yuka and other friends or family.

Yasui was not alone in attaching his name to the poem. At least two high school students in Manzanar claimed the poem as their own in class assignments. Rita Takahashi Cates cites a version signed by a Bennie Okami and submitted for an English class in early 1943 in her dissertation. And Erica Harth, in her essay “Democracy for Beginners,” notes another from “a high school boy calling himself the ‘mad Mongolian.’” Both of these versions appear to be copies, but they point to the poem’s reach as something of a mid-century meme that was circulated in multiple camps.

Equally intriguing is the multiple references to the “mad Mongolian.” In addition to the student in Manzanar, Yuriko Domoto Tsukada saved a version from her time in Amache that is also signed “The Mad Mongolian,” perhaps a copy of the poem shared in that camp. As Holly Yasui has noted, her father used this nom de plume in his jailhouse poems and letters. (See, for example, his meditation on the “sinister art” of war in “The Soliloquy of an African Ant-Eater.”) It’s unlikely that there were three different “mad Mongolians” running around three different camps, so it would seem that later copies of the poem also copied this signature.

Adding yet another complication to this poetic mystery is a story from Hide Shimizu Duncan, who also claimed to have written “That Damned Fence.” Ms. Duncan shared with a librarian at the Oxnard Public Library that she had written the poem as a seventeen-year-old in Gila River, after a frightening experience with an over-eager sentry near the camp fence — a less widely-known plot twist uncovered by Holly Yasui while researching her 2017 documentary, Never Give Up! Minoru Yasui and the Fight for Justice.

After eighty years and at least five documented claims to authorship, we may never know the poet behind “That Damned Fence” with any degree of certainty. But as Holly Yasui, who sadly passed away last year, told Campu in 2020, competing claims over the poem show how deeply it resonated with incarcerated Japanese Americans, especially those who were US citizens by right: “There was a lot of seething frustration and anger in the camps among all the nisei. And I think that the poem spoke to that…. It’s this really interesting combination of both being angry and frustrated at the situation, but also affirming this… what I would call almost fanatical patriotism.”

Regardless of whether or not an undisputed author ever emerges, it’s clear that “That Damned Fence” will remain a powerful testament to the spirit of resistance and resilience that sustained many Japanese Americans through the hardships of WWII.

—

By Nina Wallace, Densho Media & Outreach Manager

Thank you to poetry detectives Homer and Barb Yasui, Frank Abe, and my colleague Brian Niiya, whose exhaustive research on the origins of “That Damned Fence” and the timeline of Yasui’s imprisonment and the poem’s circulation in the camps was an invaluable resource for this article. The poem will appear in Abe’s forthcoming anthology of camp literature, so be sure to follow his work for more on this mystery!

References:

Charles Kikuchi diary, March 24, 1943.

Charles Bailey, City in the Sun: The Japanese Concentration Camp at Poston, Arizona (Westernlore Press, 1971), 113-114.

Erica Harth, “Democracy for Beginners” in Last Witness: Reflections on the Wartime Internment of Japanese Americans (Palgrave, 2001).

Rita Takahashi Cates, “Comparative Administration and Management of Five War Relocation Authority Camps: America’s Incarceration of Persons of Japanese Descent during World War II” (Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, 1980).