February 5, 2022

Densho Content Director Brian Niiya reviews Kenjiro Nomura, American Modernist: An Issei Artist’s Journey, a beautifully illustrated exhibition companion book and biography that completes Barbara Johns’ invaluable trilogy on major Issei artists from the Seattle area.

For much of the past two decades, Seattle-based art historian Barbara Johns has chronicled the life and work of Issei artists from the Pacific Northwest, both in the context of the burgeoning art scene there and through their World War II exile in American concentration camps. This current volume, which accompanies a new exhibition on Nomura at the Cascadia Art Museum is the last of a series of three books Johns has authored on the three major Issei artists from Seattle, the others being Signs of Home: The Paintings and Wartime Diary of Kamekichi Tokita (2011) and The Hope of Another Spring: Takuichi Fujii, Artists and Wartime Witness (2017). Johns also authored an earlier work on the younger Issei artist Paul Horiuchi, Paul Horiuchi East and West (2008).

Each of the three artists gained recognition in the 1930s in mainstream art circles as outstanding artists in the Pacific Northwest and as key exponents of a local distinctly American style despite their being immigrants from Japan. Each gained the support of key figures in the local scene and appeared in numerous local and some national shows. But as with all Japanese Americans on the West Coast, World War II upended their lives and careers and largely erased them from the annals of art history.

First coming upon the work of Tokita in the collection of the Seattle Art Museum as a staffer there in the 1980s, Johns’s research—conducted with the assistance of the families of each artist—has lifted them out of obscurity and into their rightful place in local art history, while also illuminating their previously unknown contributions to our understanding of the wartime incarceration.

Kenjiro Nomura was born in 1896 and migrated with his family to Tacoma, Washington at age ten. He was more or less on his own since age seventeen, when the rest of his family returned to Japan. Moving to Seattle in about 1915, he worked odd jobs before starting a successful sign painting business that he operated with his close friend and fellow artist Tokita. Noto Sign Company soon became a gathering place for other Issei artists. His paintings of urban landscapes, the waterfront, and the local countryside brought him recognition in the 1930s, though the Great Depression forced the closure of the sign shop. Married to a Kibei woman twelve years his junior, he had a son in 1930 and later started a successful laundry business.

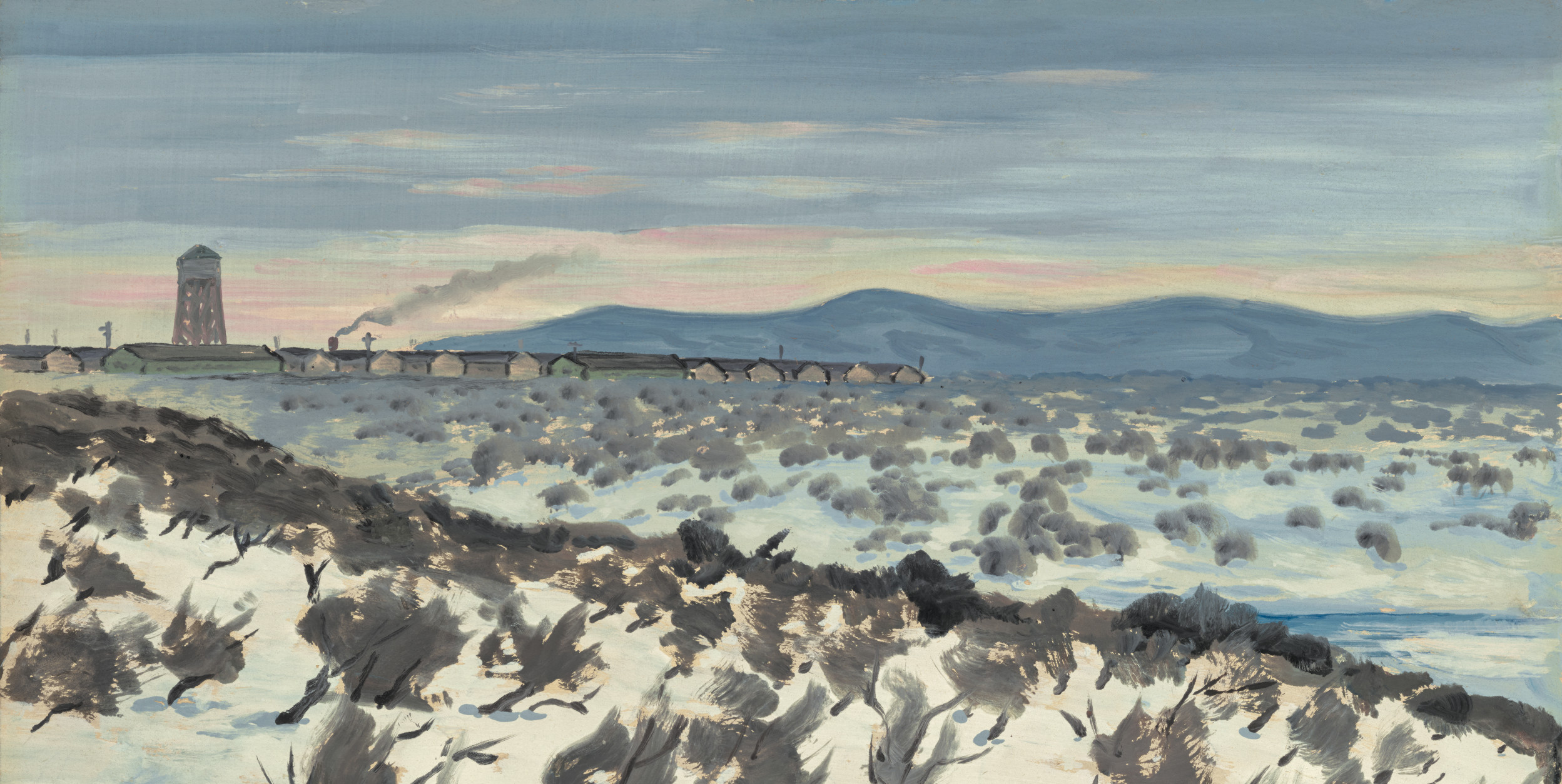

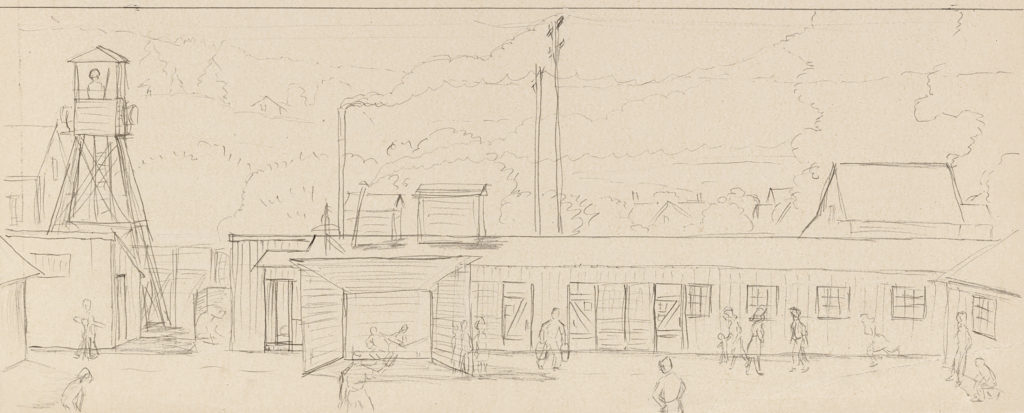

Incarcerated at Puyallup and Minidoka during the war with his family, Nomura’s watercolor paintings of the built and natural environments at the camps provide a glimpse of inmate life there from an Issei perspective. He also worked at the camp sign shop and, with Tokita, designed and painted the Nisei war memorial at Minidoka. Returning to Seattle after the war, he was the only one of the three to return to prominence as an artist after the war, even as his style changed to incorporate much greater abstraction, in the context of a growing interest in Japan in Seattle’s embrace of cosmopolitanism. He died in 1956.

In contrast to the earlier books, Kenjiro Nomura, is more or less a straight biography, missing the diaries whose translations highlight the works on Tokita and Fujii. Johns devotes chapters to Nomura’s life as an Issei before the war, his rise as an artist in the ‘30s, his wartime incarceration, and his postwar life and art. But with little in Nomura’s own voice—as well as a general lack of Japanese language sources—there is a lot we end up not knowing about Nomura and his own views about his life and the issues he faced as a Japanese immigrant and artist. To her credit, Johns displays a wide knowledge of available primary and secondary sources in English—reading the books sequentially, she has clearly gained knowledge about the Japanese American experience before and during the war in the course of writing them—and does about as good a job as one can do with the source limitations. She also provides incisive analysis of Nomura’s art in the context of trends in the local art scene.

Johns’s biography is augmented by David F. Martin’s essay that places Nomura more specifically in the context of Seattle’s art scene before and after the war. As with the other books, Kenjiro Nomura, is beautifully illustrated with images of Nomura’s artwork from before, during and after the war, as well as family photographs.

In summary, Kenjiro Nomura, is a worthy successor to the earlier books that both restores him to his place in art history and provides an important Issei artist viewpoint of the wartime incarceration in images.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

Learn more about Kenjiro Nomura, American Modernist: An Issei Artist’s Journey (University of Washington Press, 2021) by Barbara Johns here.

An exhibition of Nomura’s work is on view at Cascadia Art Museum through February 20, 2022. Densho Executive Director Tom Ikeda will join Barbara Johns for “Conversations about Nomura” at the museum on February 13th, 10-11am. Support for this event comes from the Atsuhiko and Ina Goodwin Tateuchi Foundation. Learn more and purchase tickets.

Note: Densho was consulted and listed as a partner for the exhibition and accompanying catalog, but is not receiving any monetary benefit from the sale of the book.

[Header: Untitled Minidoka landscape (sagebrush in snow), ca. 1943–1945. Oil on paper. Private collection, Promised gift to Cascadia Art Museum. Courtesy of Cascadia Art Museum, Edmonds, WA.]