April 10, 2019

If there’s one true thing about studying history, it’s that there’s always more to learn. Less (in)famous than sites like Manzanar and Tule Lake, Rohwer was one of two WRA concentration camps located in Arkansas, where inmates were exposed to the unique climate and racial politics of the South, and had regular interactions with Nisei soldiers training at nearby military facilities. This year’s Rohwer Pilgrimage will take place this weekend, and Densho Content Director Brian Niiya has collected ten little-known facts about the former incarceration site to get ready. Keep reading to learn more — and look for Brian at the pilgrimage to ask your own questions!

1. A Particularly Hostile Reaction by State Government*

The influx of Japanese Americans inspired a particularly virulent reaction from state officials led by Governor Homer Adkins, a Ku Klux Klan member, who instructed Arkansas colleges to bar Japanese American resettlers and limited their work on local farms. As a result of these policies, relatively few Japanese Americans left Rohwer and Jerome to do outside agricultural work, something that thousands of Japanese Americans did at other WRA camps.

Five anti-Japanese bills and two Senate resolutions were introduced, with an alien land law type measure that would have targeted Nisei as well as Issei passing both houses with 28-1 and 76-1 margins before being signed into law by Adkins on Feb. 13, 1943. It was later found unconstitutional. A bill that would have prohibited “members of the Mongolian race” from attending white schools failed to pass. Adkins’ successor as governor, Benjamin Travis Laney Jr., was less obstinate in opposing settlement in Arkansas after taking office in January 1945, and a handful of inmates did remain in Arkansas after the war.

2. “A Very Short Race of People”

Rower barracks had small rudimentary closets installed in individual living units. However, the closet shelves and rods were extremely low. “They must think we are midgets,” wrote Yoshie Ogata in her diary after her first day at Rohwer. “One of the amusing observations in this respect was the extreme lowness of these rods,” read a Reports Office summary of the living quarters. “The architects or engineers who planned them must have anticipated a very short race of people.”

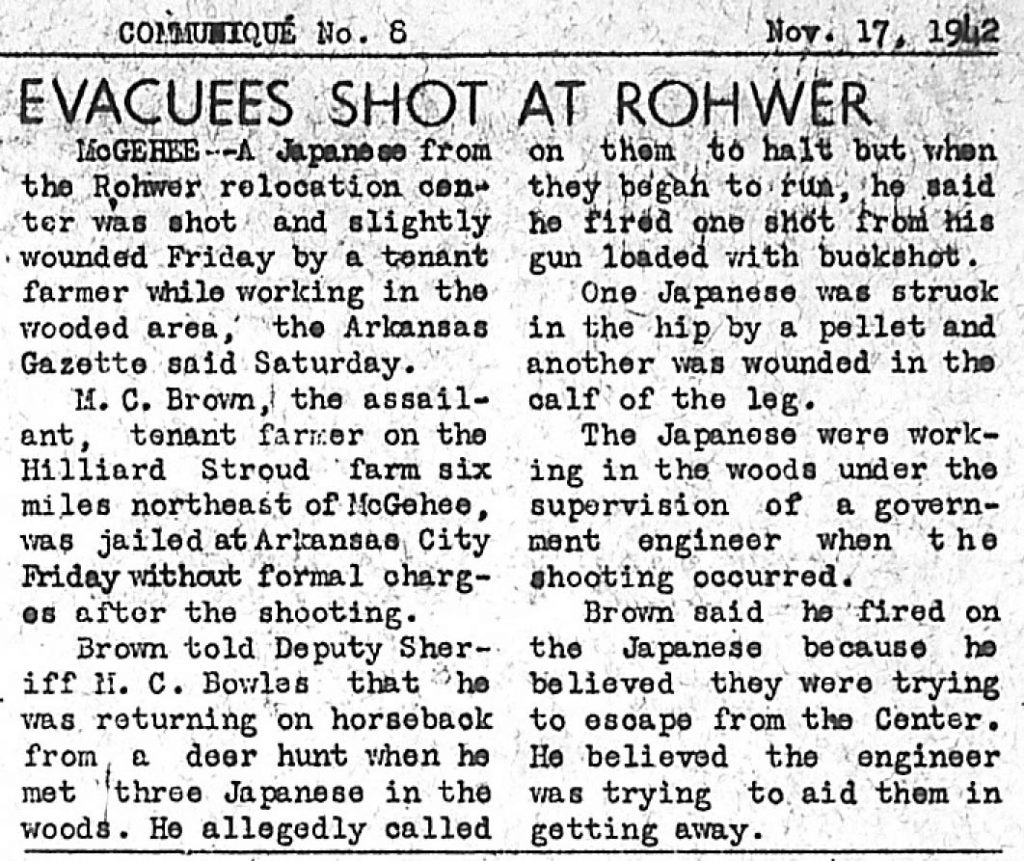

3. There were no less than three shootings of Japanese Americans in and around Rohwer in November 1942

On November 10, 1942, W. M. Wood, a 72 year old local resident, fired a shotgun at Private Louis Furushiro in a Dermott café. Furushiro managed to avoid injury beyond powder burns even though he had been less than feet away from the shooter. Furushiro, who was stationed at Camp Robinson, had been on his way to visit his sister in Rohwer.

On November 13, M. C. Brown, a local tenant farmer, shot at three Japanese Americans from Rohwer who were working outside the camp with a white overseer, wounding two of them. Brown claimed that he thought they had been trying to escape. Camp director Ray D. Johnson wrote that Brown was “a hunter who apparently was either drinking or slightly deranged.” Whatever the case, Brown managed to escape going on trial for the shooting.

Finally, a private guard hired to protect the wood supply of one of the camp contractors fired birdshot at inmates, injuring them.

4. Public Service Halls

As at other camps, one slightly smaller barrack in each block was designated for recreational use. These barracks were called “recreation halls” at all of the other WRA camps, but at Rohwer, they were called “public service halls” or “P.S. halls.” They were used in similar ways as at other camps, as makeshift churches, headquarters for clubs, venues for movie screenings, etc. The Rohwer library was initially housed in P.S. Hall 19, the dry goods store in P.S. 13, and the shoe store in P.S. 42. Perhaps the most unusual use of a public service hall was P.S. 12, dubbed “Rohwer Toyland,” a toy library inmates set up for children aged six to fifteen.

5. Zoot suits, Hollywood hair, and “early jealousies” between the Stockton and Santa Anita groups

The Rohwer population was almost equally divided between those from the Stockton and Santa Anita Assembly Centers. The former were a mostly rural population who came from Stockton, Lodi, French Camp, and other area communities; the latter included a mixture of Los Angeles city dwellers from Boyle Heights/East Los Angeles and other parts of the city, along with farmers from the southwestern and southeastern parts of Los Angeles County and communities such as Lawndale, Gardena, and Whittier.

As one might expect, initial encounters between the Stockton and Santa Anita groups resulted in a mixture of curiosity and conflict. “There is strong Santa Anita-Stockton rivalry,” Rohwer Outpost managing editor Kaz Oshiki told WRA Community Activities Supervisor Ed Marks during the latter’s October 1942 visit. A pair of Nisei from Stockton, twenty-four year old Tsugio Kubota and twenty year old Isao Buddy Sato elaborated on the relationship in 1944 interviews with Charles Kikuchi. The Santa Anita Nisei “sort of felt superior to the Stockton people as they thought we were just hicks,” said Kubota. “We sort of looked up to them in awe I guess because they were from L.A. and they really acted like they had been around.”

“At first I didn’t want to meet too many of the Santa Anita bunch as I didn’t want to be taken for a sucker,” Sato added. But the fear and fascination soon turned to mimicry. “The Stockton bunch were influenced quite a bit by the Santa Anita fellows and they were getting pretty wild,” said Kubota. “Most of the fellows started to wear drapes and let their hair grow long like the L.A. guys.” Once they started acting the part, Sato said, “we started to meet a lot of the L.A. fellows and girls. We were known as the Sharpies from Stockton and they thought we weren’t so ‘square’ when they saw how we were dressed. We always went out all draped out in style like the L.A. fellows so that we got along good.”

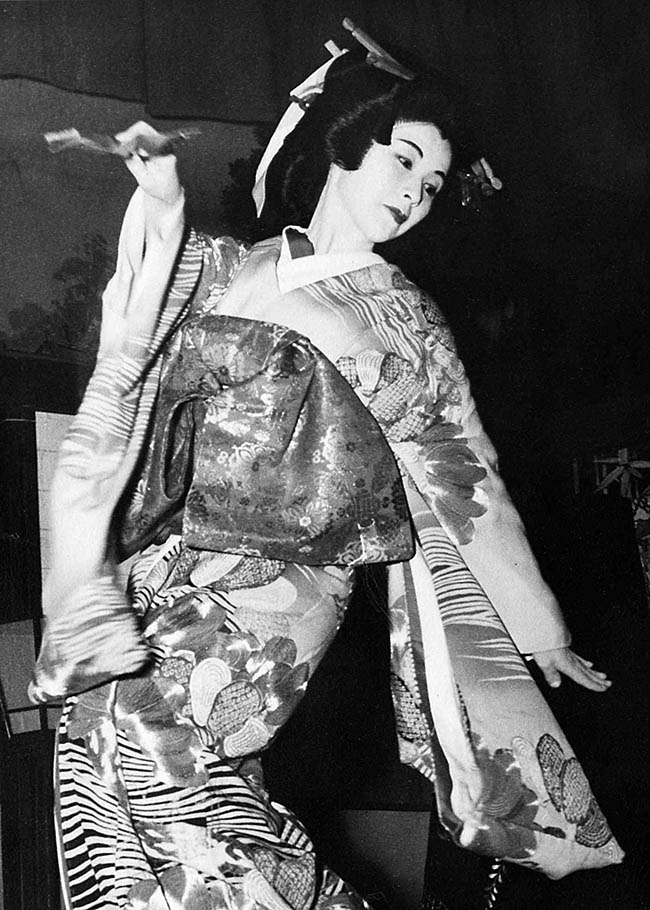

6. Legendary Dancer Fujima Kansuma

As at other WRA camps, talent shows and other performances by inmate groups served as one of the most popular forms of entertainment. A highlight for Rohwer inmates was the performances of traditional Japanese dance led by legendary dance teacher Fujima Kansuma, who had been based in Los Angeles before the war, and who was incarcerated at Rohwer. Along with some of her students, Kansuma performed at Santa Anita and Rohwer and also traveled to Jerome to put on shows there.

One of Kansuma’s students, June Berk, wrote that the “Japanese dance performances lifted the morale of the Issei and Nisei who had to live behind barbed wire fences.” A 1990 reunion booklet recalled that she produced shows “with such impeccable costumes, precision and staging that the viewers were virtually transported into another world and relieved for a few hours of the deplorable and futile life in a concentration camp.” Kansuma would resume her teaching in Los Angeles after the war and recently celebrated her 100th birthday.

7. An unusual ally in assistant Director Joseph Hunter

Most of the administrative staff at Rohwer were white Southerners, including both locals from southeast Arkansas and those from other parts of the South. According to Community Analyst Charles Wisdom, the non-Southerners on the staff considered the Southerners “to be basically unfriendly, or at best indifferent to the evacuees.” One exception was Joseph Boone Hunter, the chief of community services and one of three assistant directors at Rohwer under Project Director Ray D. Johnston.

Hunter had an unusual background. Born in Allen, Texas in 1886, he was an army chaplain in France in World War I. After gained an M.A. degree from Vanderbilt University in 1920, he went to Japan as a missionary for the Disciples of Christ and taught there as well. He met his wife, fellow missionary Mary Cleary, there, and their two children were born in Japan. Returning to the U.S. in 1926, he began doctoral studies at Yale, but ended up moving to Little Rock to become the founding pastor of Pulaski Heights Christian Church, remaining there until 1940.

After another trip to Japan in 1941, Hunter aided Japanese Americans incarcerated at Santa Anita and Manzanar before being hired at Rohwer. In his position, he oversaw many of the areas that involved interaction with the inmates including education, recreation, and religion. Given his experience in Japan, he was the staff “expert” on Japanese culture and psychology. He left Rohwer at the end of September 1944. According to Wisdom, the community management staff under Hunter were the most friendly to the inmates and Hunter himself “was considered excessively pro-evacuee and even pro-Japan by many of the staff.” Hunter remained in Arkansas after the war and was a key figure in early preservation efforts of the Rohwer Cemetery in the 1960s.

8. Private Schools Amidst a Public Disgrace

Rohwer inmates organized two kinds of private schools. Though not technically permitted, many inmates operated private Japanese language schools for children out of their barracks, which the WRA knew about, but was unable to prevent. As with prewar Japanese language schools, sessions ran on weekday afternoons and evenings after regular school and on Saturdays. A community analysis report claimed that, “It was the opinion of many Nisei here that Japanese language schooling increased at Rohwer over what it had been prior to evacuation.”

With the end of the 1944–45 school year, Rohwer administrators announced that the schools would be shut down for the duration given the camp’s imminent closure. This was done in part to encourage Rohwer inmates to leave. But as the fall of 1945 approached, thousands of inmates remained in Rohwer, a disproportionate share of whom were children. In response, the Rohwer Community Council began plans to start its own school. Though the administration opposed this effort, after a series of negotiations, it did agree to allow such schools as a vehicle to keep children occupied in the last days of the camp. Rohwer was one of the last camps to close, with the last inmates leaving on November 30, 1945.

9. The Jerome Influx

While other WRA camps were seeing their populations gradually decline through 1943 and 1944 as inmates began to leave to “resettle” in areas outside the West Coast restricted area, Rohwer’s population suddenly increased by over a third with the arrival of 2,489 people from Jerome upon that camp’s closing in the summer of 1944. According to the first Rohwer Reunion Booklet, the arrival of the Rohwer group brought the camp population back to nearly its peak “and camp activities were jumping again.”

10. Preserving the Rohwer Cemetery

In the decades after Rohwer’s closing, the camp cemetery has become the focus of preservation efforts and a symbol of the camp. Led by former Rohwer inmates and Hunter, the cemetery was dedicated as an Arkansas State Historical Park on 1961. Through Hunter’s efforts, the Desha County American Legion began to care for the site, and memorial services were held there in 1961, 1966 and 1969. The site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. Later, Sam Yada, a former Rohwer inmate who settled in Arkansas after the war, led an effort to build a new monument at the cemetery, which was dedicated on Memorial Day in 1982.

The cemetery became a National Historic Landmark in July of 1992, and a new granite monument with bronze plaques was dedicated. That same year, a stabilization project for the bases of the original monuments was completed. In 2011, a coalition led by the University of Arkansas Little Rock received a Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant to restore the monuments and another in 2014 to restore the twenty-four headstones.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

*This is true for the Jerome concentration camp as well, which was also located in Arkansas.

The information presented here has been excerpted from Densho’s new and improved Sites of Shame project, coming to a device near you in 2020. Full citations will be included there, but feel free to post questions in the comments or email us at info@densho.org in the meantime!

[Header image: Original WRA caption: “Rohwer Relocation Center, McGehee, Arkansas. In contrast to most of the relocation center sites, many of the blocks in the Rohwer Center are shaded by trees. The residents have done much to make their tar paper barracks more livable by the planting of flowers and vegetable gardens and the building of rustic walks and bridges. This view is in block 7.” June 16, 1944. Photo by Charles E. Mace, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]