March 26, 2019

Setsuko Matsunaga Nishi was born in Los Angeles on October 17, 1921, the second of four children—and oldest of three sisters—of Hatsu and Tahei Matsunaga. She grew up in a very musical family, and dreamed of becoming a concert pianist in her early years. After graduating from high school, she enrolled at the University of Southern California as a music major. But with the onset of World War II, and growing pressure to oust Japanese Americans from the West Coast, Setsuko was unable to pursue a career in music and instead set down a very different path.

During her junior year at USC, Setsuko switched her major to sociology and was elected to the honor fraternity Phi Beta Kappa. Meanwhile, in contrast to many other Japanese Americans, she moved to take action to defend her community. Joining her friend Masamori Kojima, plus liberal minister Rev. Fred Fertig and a group of brothers from the Maryknoll mission in Boyle Heights, she organized a speakers’ bureau and worked to organize “information meetings” to counter hysterical news media and political rhetoric villainizing Japanese Americans.

As the shadow of mass removal loomed over the community, Setsuko wired President Roosevelt to urge him not to take arbitrary action. Her telegram, sent from Los Angeles on February 10, 1942, and preserved in White House files, read “THE PRESIDENT: WE NISEI AMERICANS LOYAL. PROTEST INTERNMENT AS UNDEMOCRATIC CURTAILMENT OF CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS AND CIVIL LIBERTIES.” Nine days later, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066.

Despite Setsuko’s efforts to avert mass removal, in spring 1942 the Matsunaga family was sent to Santa Anita Assembly Center. In fall 1942, Setsuko and her sister Helen were among the first students to leave camp under the auspices of the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council. Following a harrowing journey across the country, she arrived in St. Louis and enrolled in the M.A. program in sociology at Washington University. While in St. Louis, Setsuko made two important contacts. First, she was visited by sociologist Tamotsu Shibutani, who recruited her as an “Assistant Research Coordinator” for the UC Berkeley-based Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS). Second, she met P.L. Prattis, editor of the African American newspaper the Pittsburgh Courier, who remained an important mentor in the years to come.

Following graduation from Washington University in 1944, Setsuko moved to Chicago, where her parents had settled after leaving camp, and enrolled as a doctoral student in the famous University of Chicago sociology department. There she participated in JERS seminars led by director Dorothy Swaine Thomas and provided information on conditions in Chicago for People in Motion, the official government-commissioned study of Japanese American resettlers.

In Chicago, Setsuko met Ken Nishi, a California-born painter who was then serving as a non-commissioned officer in the U.S. Army. The two were married in 1944 and, in the years that followed, had their first child, Geoffrey. Despite carrying the burden of childcare, Setsuko nonetheless took employment outside the home, and served as chief family breadwinner.

Meanwhile, Prattis hired Setsuko as an assistant (and ghostwriter) for the Pittsburgh Courier, and she also worked as a research editor for the Chicago Defender. In 1944, Prattis introduced her to the celebrated African American sociologist Horace R. Cayton, who became a longtime friend and collaborator. Cayton engaged her as a staffer at Parkway Community House, a settlement house he directed in the city’s South Side Black Belt. With Cayton’s guidance, Setsuko helped found the Chicago Resettlers Committee, a social service agency that connected former incarcerees with resources to rebuild their lives, now known as the Japanese American Service Committee. Meanwhile, with funds from the American Council on Race Relations (arranged through Robert Weaver, later the first African American to serve as a cabinet secretary in the Executive Branch), she wrote an extended pamphlet, “Facts About Japanese Americans” (1946), which received wide distribution. She simultaneously authored a review of Miné Okubo‘s graphic memoir Citizen 13660, for the American Sociological Review.

In addition to serving with the Chicago Resettlers’ Committee, in the late 1940s Setsuko assumed the position of acting head of the Chicago Council Against Racial and Religious Discrimination, a coalition of civil rights and labor groups. She went on speaking tours, and lobbied for a statewide Fair Employment Practices Bill, testifying at hearings in the state capitol in Springfield.

Courtesy of the Joseph P. Healey Library, University of Massachusetts Boston.

Although she completed her comprehensive doctoral exams at University of Chicago by 1951, Setsuko was obliged to put off completion of her dissertation and seek paid employment to meet her growing family responsibilities. Ken had undergone extensive hospitalizations, and even after his recovery, he struggled to support himself as an artist.

At the start of the 1950s, the Nishis moved to Tappan, New York, outside New York City, and had four more children. Once in New York, Setsuko was named to a position in the Research Department of the National Council of Churches. She in turn hired Horace Cayton as a research adviser, and they collaborated on a book, The Changing Scene (1955), part of a two-volume study of churches and social service.

In 1963, Setsuko completed her dissertation and received her long-delayed doctorate. Her dissertation, “Japanese American Achievement in Chicago: A Cultural Response to Degradation,” studied the resettlement and adaptation of Japanese American former inmates in postwar Chicago. While her text celebrated the community structures that enabled Japanese Americans to reestablish themselves, she bitterly criticized “model minority” notions of Asian American success as simplistic and biased. Decades later, in 2005, her dissertation was at the center of a controversy over scholar Jacalyn Harden’s assertions that Setsuko and other Nisei social scientists had presented the Nisei as culturally superior to African Americans. Setsuko bitterly opposed any such contention, and she went so far as to produce an open letter in the pages of Amerasia Journal in which she denounced Harden for distorting her work and strongly requested that the author and her publisher issue a retraction.

In 1965, Setsuko was appointed professor of sociology at Brooklyn College and the Graduate School of the City University of New York, where she taught the school’s first Asian American Studies courses and served as a mentor to a generation of scholars. She didn’t engage in much academic publishing during the following years. Instead, as in Chicago, she pursued work as a self-described “scholar/advocate,” bridging the gap between academia and community activism. Her most significant affiliation was with the Metropolitan Applied Research Center, the noted think tank of the civil rights movement led by Dr. Kenneth B. Clark and Dr. Hylan Lewis.

In the 1970s, Setsuko was appointed to the New York State Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, where she served for thirty years, including six as chair. She was also active in Japanese American community activities, testifying before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in 1981, and collaborating with Japanese American and Jewish community leaders on the use of the phrase “concentration camps” in connection to the landmark America’s Concentration Camps exhibition in 1998.

Setsuko retired from Brooklyn College in 1999, but she continued to receive some important honors in the following years. In 2007, she was presented with a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Association for Asian American Studies. In June 2009, she was conferred The Order of the Rising Sun with Gold Rays and Neck Ribbon by the Government of Japan. In May 2012, six months before her passing, she returned to the University of Southern California as one of the Nisei former students who received honorary degrees in place of the diplomas they had been unable to complete due to mass removal.

In her last years, Setsuko organized and served as director of the Japanese American Life Course Survey, a large-scale investigation into the long-term effects on Japanese Americans of their wartime incarceration—though it remained unfinished when she died on November 18, 2012, shortly after her 91st birthday.

—

Adapted from Greg Robinson’s Densho Encyclopedia article on Setsuko Matsunaga Nishi

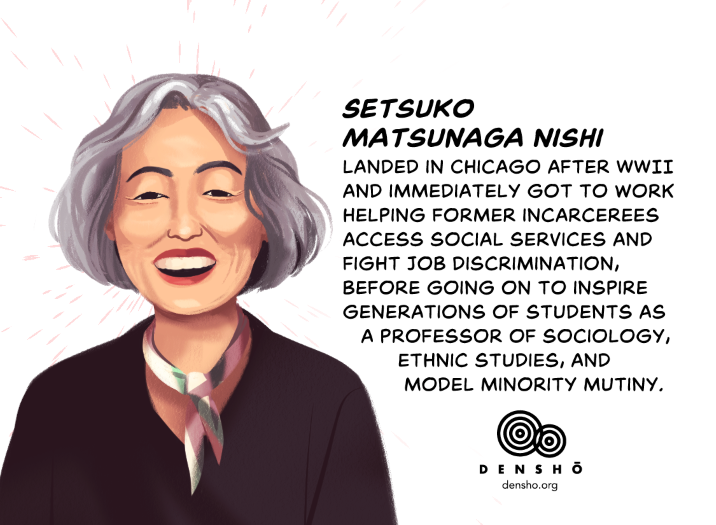

Header image: original artwork by Kiku Hughes. Kiku is a comics artist living and working in the Seattle area. Her work has been featured in “Beyond: A Queer Sci-Fi and Fantasy Comic Anthology”, “Elements: Comic Anthology by Creators of Color” and Short Box Comics Collection. She is currently working with First Second Books to publish her first graphic novel, about Japanese American incarceration. Funding for Kiku’s work was generously provided by a grant from the Seattle Office of Arts & Culture.