August 13, 2015

By the 1920s, swimming in public pools had become a hallmark of modern American life. As Jeff Wiltse writes in Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America, “Municipal swimming pools were extraordinarily popular during the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. Cities throughout the country built thousands of pools—many of them larger than football fields—and adorned them with sand beaches, concrete decks, and grassy lawns. Tens of millions of Americans flocked to these public resorts to swim, sunbathe, and socialize. In 1933 an extensive survey of Americans’ leisure-time activities conducted by the National Recreation Association found that as many people swam frequently and went to the movies. Furthermore, Americans attached considerable cultural significance to swimming pools during this period. Pools became emblems of a new, distinctly modern version of the good life that valued leisure, pleasure, and beauty. They were, in short, an integral part of the kind of life Americans wanted to live.”

The logic and repercussions of racial exclusion from public pools, then, encompassed much more than the recreational activity itself. Instead, it spoke to what kinds of citizens and bodies were deemed worthy of engagement in mainstream American identity.

Yoni Appelbaum, senior editor of The Atlantic, noted in a recent interview that, “Pools have really been a site of racial and class conflict in America as long as they’ve been around. By the 1920s, we started to redefine pools as social sites, as places of leisure and recreation. Men and women used them together, and that’s when most of the racial restrictions were imposed in the north, mirroring the segregation that already existed in the American South.”

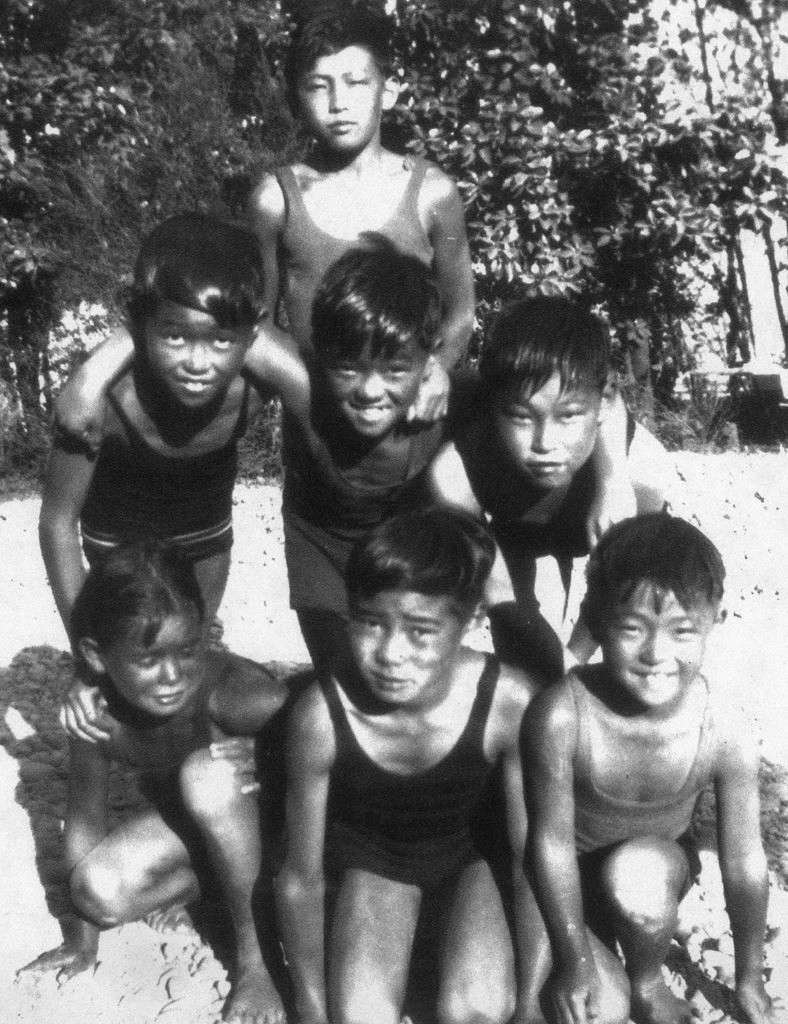

The exclusion of non-white bodies from public swimming places spanned geographic and racial boundaries. Japanese Americans growing up in pre-World War II Seattle remember facing discrimination at the city’s swimming pools. Several interviews in the Densho Archives demonstrate how that community was impacted by and sought to overcome racial exclusion from public pools.

As Art Abe recalled, “I remember one instance, one of my friends had a birthday party, and the mother decided that she’d treat the kids to swimming at the Moore pool in Seattle. And all of us went down there with our swimming suits, and they declined to admit me to the pool. And the mother didn’t say anything, the rest of ’em went in and had a good time, and I was left out. That was the first time I’d encountered discrimination in grammar school.”

Similarly, Yosh Nakagawa noted that even if racial exclusion wasn’t clearly stated at Seattle pools, it was implied, “You could not go to Colman swimming pool at Lincoln Park and swim, and that was a public park…if it didn’t say ‘No Japs Allowed,’ it was very clear it was ‘whites only.'”

Following their release from WWII incarceration, Japanese Americans continued to face discrimination and exclusion from many public places. Even so, there were instances in which they put their own interests aside in order to support other marginalized groups. In an oral history interview with Densho, Joe Ishikawa talked about how he worked with members of the black community to desegregate a swimming pool in Lincoln, Nebraska:

“When I went to the city hall to get the tickets to pass around, they said, ‘Don’t give any tickets to the black children’ or, ‘the colored children,’ they said. ‘Colored’ was an accepted word at that time. So I said, ‘Well, you’d better keep them all. I’m not going to sneak around and hand out tickets here and there and pass up others.’ And the more I thought about it, the madder I got. And so I decided I would resign, and I sent in a letter of resignation and sent a letter, sent a copy to all the playground directors in the city [….]

“And anyway, nothing was happening, so I decided I’d go to the city hall and talk to them at a city council meeting. I said, ‘You’re in violation of the state statute.’ [….] And the upshot was that they said, ‘Not one black has asked for, or not one colored person has asked for what you’re asking for.’ And they said, ‘Would you be happy if they, if we made a swimming pool in the colored neighborhood?’ And I said, ‘No, that’s not, that’s still in violation of your statute.’ And they said, ‘Not one colored person has asked for what you’re asking for.’

He went on to describe building a coalition of supporters and working with them to gather a crowd of people to attend a City Hall meeting:

“So I went to the Urban League, and I was active with the NAACP anyway, so I went to them and told them what was happening, and went to some of the black preachers. And we had over two hundred people there, at least half of them black. And other people were very helpful were some veterans coming back from the war, American Veterans Committee[….] And so they had no choice but to open the swimming pool. And then a cold spell set in, so nobody went to the swimming pool. And the guy tried to, the playground director tried to blame it on the fact that they had opened the swimming pool, and so I got a friend of mine, one of the AVC guys who went down and did some research on temperature tables and we gave them all these temperature tables, told them that was probably the reason. And anyway, it stayed open after that, but you know, it was not a big thing. It seemed big at the time, and in a way it was kind of a defining moment for me.”

Watch Mr. Ishikawa discuss this defining moment in his life:

Actions like Mr. Ishikawa’s ultimately led to the desegregation of public spaces across the U.S. However, the privatization of swimming pools has allowed for a more covert exclusion. The community pools of today are often under the jurisdiction of homeowner’s associations, clubs, and other private groups that control who is permitted to enter. While there are many pools that are truly open to all, the attack in McKinney earlier this summer is a reminder of the potential that public pools have to be contested, racialized spaces.

So, as you’re savoring the final days of summer swim weather, take a moment to acknowledge the underlying histories of struggle and privilege that have shaped—and at times come to the surface of—public pools.

—

Natasha Varner, Densho Communications Manager