January 4, 2018

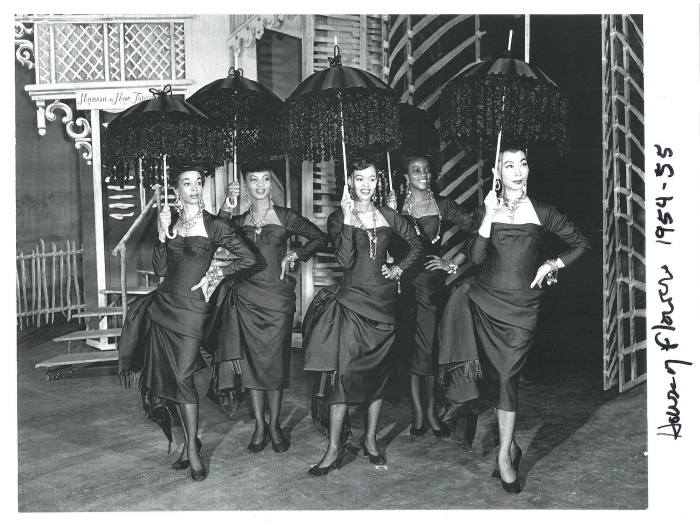

Mon Toy was born Mary Teruko Watanabe in Seattle, Washington and grew up there before the war. She married just prior to the war and with her husband, was forcibly removed along with all other West Coast Japanese Americans, going first to the Puyallup Assembly Center, then to the Minidoka, Idaho, concentration camp. Estranged from her husband in camp, she left alone to “resettle” in New York. In the big city, she worked as a secretary, while studying voice at Julliard. She then embarked on a career as a showgirl, which eventually led to roles in Broadway productions of House of Flowers in 1954 and The World of Suzie Wong in 1958 and later to a career as a character actress on TV and in movies. She was also politically active in advocating for Asian American entertainers and against “yellowface” casting later in her life.

When she began her career in entertainment, she made the decision to take the name “Mary Mon Toy” and to assume a Chinese American identity. She joined a number of Nisei who came to similar conclusions.

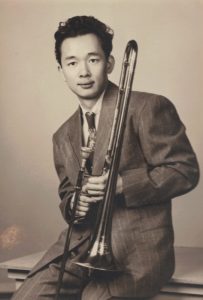

In careers that began prior to the war, actress Pearl Suyetomi performed as “Lotus Long,” while dancer Dorothy Takahashi became Dorothy Toy, half of the famed Toy and Wing dance act. Later, Kimiye Tsunemitsu performed as Trudy Long, though in her case, “Long” was her real married name after she married a Chinese American who had Anglicized his name to “Long.” Harry Kitano, who would become well-known as a pioneering sociologist, performed as a jazz musician under the name Harry Lee.

The most famous case is undoubtedly that of Jack Soo, who was born Goro Suzuki. Having performed in nightclubs before the war, he performed at many events while incarcerated at Topaz. When he left camp and resumed his career in entertainment, he adopted the Chinese American name. He later landed one of the leads in Flower Drum Song both on Broadway in the movie version, and is perhaps best known for his role as Sgt. Nick Yemana in the 1970s TV sitcom Barney Miller. I was a fan of that show as a kid and was puzzled as to why the Japanese American actor playing a Japanese American character had a Chinese American name.

There were some more unusual cases as well. Singer Elsie Itashiki recorded at least a couple of albums as “Teal Joy” in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Since her albums feature her prominently on their covers, she wasn’t exactly hiding her Asian ancestry, and I suppose “Teal Joy” sounds less Japanese—and easier to pronounce—then her birth name. For whatever it’s worth, her Nisei contemporaries Pat Suzuki and Ethel Azama recorded and performed under their real names.

“Guy Brion” became half of a popular nightclub act in the early 1950s. He told reporters as the time that he was of “Hawaiian, Japanese and French descent.” This was a little odd, since he was already well known in Hawai’i, where he had been born and raised, as James Shigeta, his birth name. He had even won the Ted Mack Amateur Hour finals under that name. Going back to his real name in the late 1950s, he went on to a notable career as an actor, being just about the only Asian American male to play romantic leads in Hollywood movies since Sessue Hayakawa in the 1910s.

(There were also a number of Japanese American writers and visual artists who changed their names so as to hide their ethnicities, but that’s a somewhat different phenomenon, since one didn’t see their faces in the course of enjoying their artistry.)

In the Japanese American press of the time, it was well known that all of these performers were actually Japanese American. In particular, Larry Tajiri, a columnist and former editor of the Pacific Citizen who was also the drama critic for the Denver Post, kept careful tabs on Japanese American entertainers and kept his readers up to date on the accomplishments of those who had adopted non-Japanese names, always reminding readers that they were, in fact, Japanese American.

But unlike the others, Mon Toy kept her Japanese American identity secret from Tajiri and other chroniclers and the Japanese American community at large. Outside of immediate family members, few knew her real ethnic background even towards the end of her life.

In 1973, she landed a role in Santa Anita ’42, one of the first plays to depict the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans. Written by Allan Knee, it was produced off-off-Broadway in 1973–74 and again in 1975. (She, along with most of the rest of the cast, appeared in both stagings.) According to Marnie Mueller, Mon Toy’s close friend and biographer, she didn’t tell anyone involved with the play about her ethnic background and that she herself had been incarcerated in a camp very much like Santa Anita.

Given the rampant anti-Japanese sentiment that existed before, during, and immediately after World War II and the fact of their Asian physiognomy, adopting the stage identity of a “good” Asian group was a logical reaction by Japanese Americans aiming for a career in the public eye. This phenomenon largely came to an end by the 1950s, given the turnabout in the image of Japan and of Japanese Americans in the postwar era, though performers like Soo, who had already attained a measure of fame under their Chinese American stage names, kept them throughout their careers.

The recent best-selling novel China Dolls by Lisa See brings this era back to life. It features as one of its main characters a Nisei woman who is a dancer in Chinese themed nightclubs of the ’30s and ’40s who takes on a Chinese stage name and passes as Chinese American. The part about that character being able to evade forced removal and incarceration—at least for a time—is made up, however.

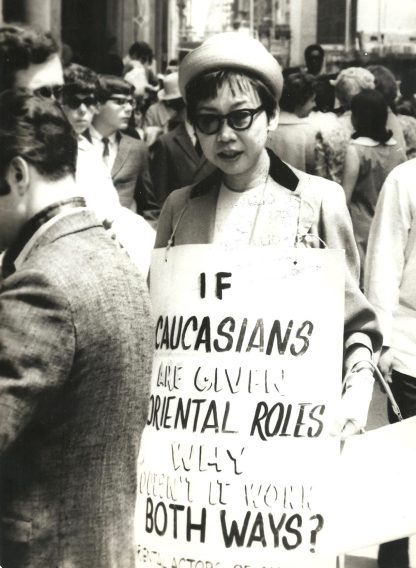

You don’t see this particular phenomenon anymore, in large part because there aren’t really “good” and “bad” Asians anymore—at least not when it comes to East Asian Americans. But some of the underlying issues remain for Asian Americans performers who must still battle “yellowface” casting practices and who are still underrepresented in mainstream productions. And maybe I’m cynical, but if political winds were to change, it wouldn’t be surprising to see this again someday.

There’s a fascinating new Densho Encyclopedia article up on Mon Toy, written by Marnie Mueller. You might remember Mueller as the author of the novel The Climate of Country, which was set in Tule Lake and loosely based on the experiences of her parents, WRA staff members there. A resident of New York City, she met Mon Toy late in the latter’s life, and the two became close friends. Mueller eventually became Mon Toy’s caretaker, and after her passing in 2009, the executor of her estate. She is putting the finishing touches on a book length biography of Mon Toy.

We are hoping to work with Mueller to digitize some of Mon Toy’s wonderful collection of photographs, programs, scrapbooks and so forth documenting her life and career. And we await Mueller’s book on Mon Toy. In the meantime, enjoy Mueller’s encyclopedia article, along with a few of the images.

—

By Densho Content Director Brian Niiya

Material on Mary Mon Toy based on the research and collection of Marnie Mueller and on her Densho Encyclopedia article on Mon Toy.

[Header photo: Mary Mon Toy (far right) in the 1954-1955 Broadway production of House of Flowers. Photo by Arthur Zinn. Courtesy of Marnie Mueller.]