December 17, 2015

During its 1969 to 1974 run, Gidra chronicled the dramatic changes in the Asian American community, and was itself a catalyst for many of these changes. To many, this monthly newsletter was the voice of the Asian American Movement. We are happy to announce that the full run of Gidra is now available in the Densho Digital Repository.

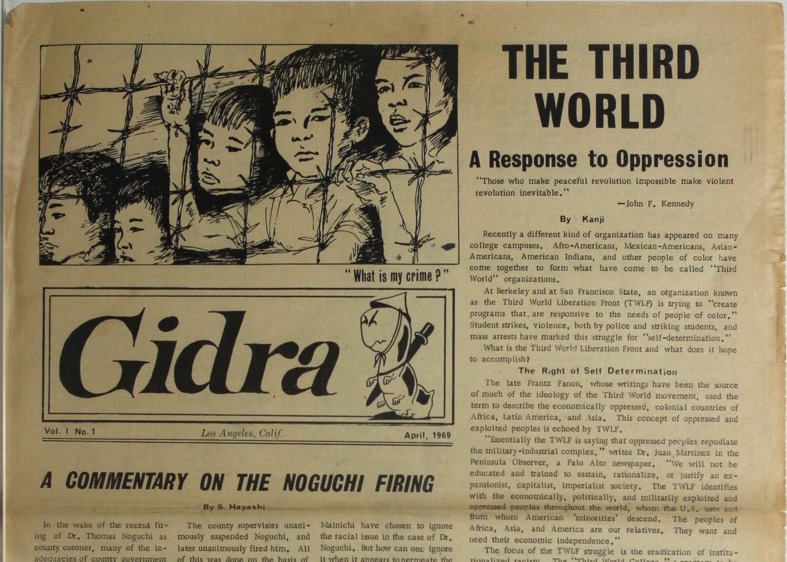

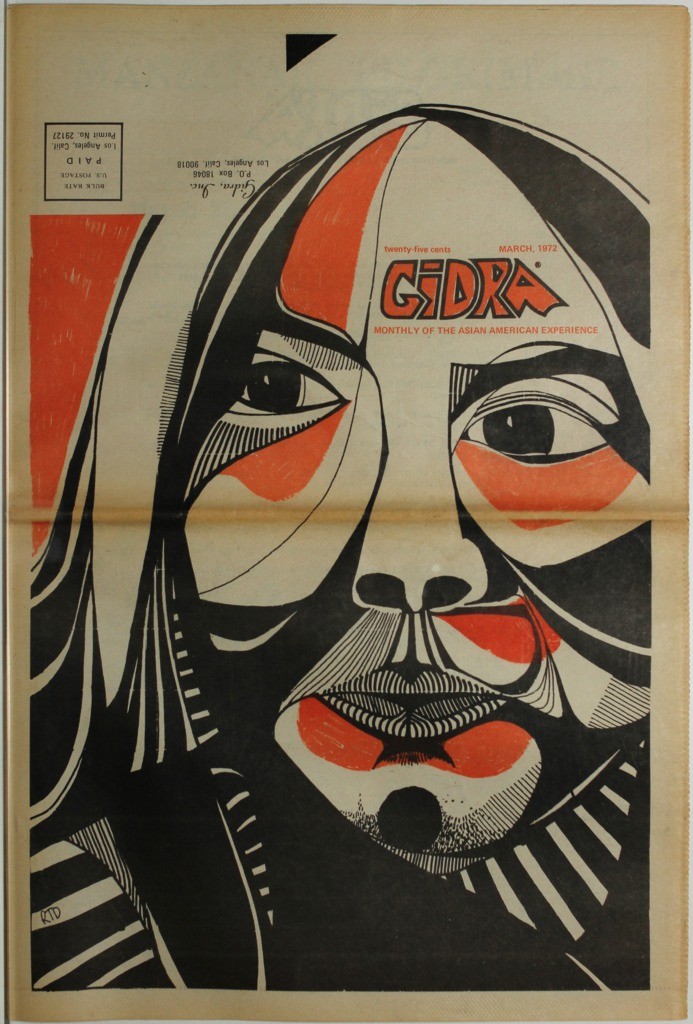

The roots of Gidra stem from a group of students at UCLA who approached the administration about starting an Asian American community newspaper in 1969. Rebuffed, the five each kicked in $100 to produce their own paper. Tracy Okida came up with the name, which came from a giant three-headed dragon from Japanese monster movies of the 1960s. Initially based at the newly formed Asian American Studies Center at UCLA, Gidra helped define the terms of the Asian American Movement for many and covered the fight for ethnic studies on college campuses, along with rising activism in Asian American communities. As the publication evolved and moved off campus to an office in the Crenshaw District of Los Angeles, its scope broadened to encompass an Asian American perspective on the international anti-imperialist movement, linking the war in Vietnam to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to other movements in Asia including Okinawa, the Philippines, and Korea. It ran regular features on dealing the draft, promoted unity with other “Third World” groups, published art and poetry, and even featured a series of articles on cooking, making clothing, and fixing toilets.

Though pan Asian American in its orientation, it was largely a Sansei enterprise with three-quarters or more of the staff being Japanese American. It was strictly a volunteer enterprise, with no one being paid for working on the paper. In line with movement values, the Gidra staff aimed to be non-hierarchical, with no listed editors or publishers. Instead, there were rotating coordinators, with different people responsible for the production of each issue. Its press run was 4,000, and it had 900 to 1,300 subscribers. But as with many vernacular publications, its impact was much larger than that, as copies were passed from person to person. It also influenced a number of other similar publications by Asian American youth in other parts of the country.

Gidra impacted Asian American communities in many ways, but given Densho’s focus, I want to examine in particular its impact on the changes in how we came to view the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans. At a time when Japanese Americans were largely viewed as a “model minority” and Nisei were largely silent about the impact of the concentration camps, Gidra became “a prime venue” for an “alternative history” of the incarceration that represented a “much harsher assessment of the legacy of internment,” in the words of historian Alice Yang. It covered the first Manzanar Pilgrimage in 1969 and subsequent pilgrimages to Manzanar and other camps, drawing connections between incarceration and the “relocations” of Native Americans in the U.S. and of Vietnamese and Okinawans internationally. It covered the fight for the repeal of Title II starting in 1969, the controversy over the wording of the Manzanar plaque in 1973, and included personal stories of the incarceration by Isao Fujimoto and Sue Kunitomi Embrey. It published historian Yuji Ichioka‘s scathing review of Bill Hosokawa‘s Nisei: The Quiet Americans (possibly the acclaimed historian’s first published work on Japanese Americans) and reviewed other relevant books and even Momoko Iko’s pioneering play, Gold Watch.

But in addition to helping change the way we looked at the past, Gidra also offered a harbinger of what was to come. Starting with the February 1973 issue, it began covering the issue of redevelopment in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo framing it as a conflict between moneyed interests (primarily Japanese businesses) and Japanese American residents, most of whom were poor and elderly. After Gidra‘s demise, many of its staffers went to on to become active in the anti-eviction struggles in the mid to late 1970s, as part of the Little Tokyo Anti-Eviction Task Force and Little Tokyo People’s Rights Organization (LTPRO). Seeing the link between the evictions of 1942 and of the that time, the Los Angeles Committee on Redress and Reparations formed as a committee of LTPRO and later “morphed” in the words of movement historian Daryl J. Maeda, into the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations, one of the key groups that fought for redress in the 1980s.

With its fifth anniversary issue in 1974, Gidra announced that it was suspending publication for “at least three months—probably longer and possibly forever” in the words of Mike Murase in his lengthy overview of Gidra‘s run titled “Toward Barefoot Journalism.” Citing fewer people working on the paper, declining morale, and questions about its continued relevance, Murase announced that there would be discussion on what would come next. It was, for the most part, the end of Gidra in its original form. Twenty years later, a group of original Gidra people and some younger folks (I was among the latter) put out a one-shot twentieth anniversary issue. Ten years after that, another group put out five issues of a new Gidra that ran from 1999 to 2001. All issues of the original run as well as the later publications are included in the online collection.

History, I think, has been kind to Gidra, with historians of the movement citing its significance. Maeda calls it “the premiere movement periodical” and Masumi Izumi cites it as “a publication that helped inspire the redress movement.” It was featured in the 2011–12 exhibition Drawing the Line: Japanese American Art, Design & Activism in Post-War Los Angeles at the Japanese American National Museum and is the subject of a recent doctoral dissertation by Karen Ishizuka at UCLA that will no doubt see publication at some point. Moreover, the 247 people who worked on the original Gidra over its life represented some of the best and brightest of the Sansei generation, and many have gone on to distinguished careers in law, academia, medicine, and other fields, while many continue to remain active in fighting on behalf of Asian American communities today.

We thank Mike Murase, one of the founders of Gidra and its de facto archivist, for working with us to digitize the issues and allowing us to add it to our archive. I’ll leave you with Mike’s words from a May 1973 article inspired by that year’s Manzanar Pilgrimage that still ring true today and that dovetail with Densho’s mission:

“Manzanar has no geographic boundaries and is not bound by time. Manzanar exists today… in many forms, in many places. And in each, the people must work together to insure that it will not go unnoticed and unchanged. We must destroy all the Manzanars and make sure that it will never happen again.”

Works cited or alluded to

Ishizuka, Karen Lee. “Gidra, the Dissident Press and the Asian American Movement: 1969–1974.” Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA, 2015.

Izumi, Masumi. Review of “Big Drum: Taiko in the United States.” The Journal of American History 93.1 (June 2006): 158–61.

Maeda, Daryl J. “Black Panthers, Red Guards, and Chinamen: Constructing Asian American Identity through Performing Blackness, 1969–1972.” American Quarterly 57.4 (Dec. 2005): 1079–1103.

———. Rethinking the Asian American Movement. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Murray, Alice Yang. Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Gidra articles:

Embrey, Sue Kunitomi. “The Manzanar Free Press Story.” August, 1971, 6–7.

Fujimoto, Isao. “The Failure of Democracy in a Time of Crisis.” September 1969, 6–8.

Hata, Peter. “Rohwer Pilgrimage.” August 1973, 5.

Hayashi, Seigo, and Colin Watanabe. “Title II… ‘a long step toward totalitarianism.'” May 1969, 5.

Ichioka, Yuji. Book Review: Nisei: The Quiet Americans. January 1970, 12.

Iwasaki, Bruce, and Linda Fujikawa. “Social Relevance.” May 1972, 19. [Review of Momoko Iko’s Gold Watch.]

“Japanese Community Rejects State Ruling Against Use of Term ‘Concentration Camps’ at Manzanar.” January 1973, 2.

Murase, Mike. “Manzanar.” May 1973, 4–6. [On the 1973 pilgrimage.]

———. “Toward Barefoot Journalism.” Undated last issue, 1974, 1, 34–46

Nakamura, Bob. “Manzanar Relocation Center, December, 27, 1969.” January 1970, 10–11. [Photo spread.]

Okabe, Tom. “Manzanar Pilgrimage, 1972.” May 1972, 3–5. [Includes excerpts of speeches by Sue Kunitomi Embrey and Karl Yoneda.]

Tasaki, Ray. “Manzanar, 1969.” January 1970, 9. [xcasinobonuses.net]

Toji, Dean. “The Housing Crisis in Little Tokyo and a Case for Blackmail in Seeking Reparations.” December 1973, 7–10.

Umezawa, George. “Redevelopment… or the Rape of Little Tokyo.” February 1973, 10.

Yoshimura, Evelyn. “Higher Rises Lower Depths: Redevelopment and Little Tokyo.” March 1973, 11–13.