September 25, 2018

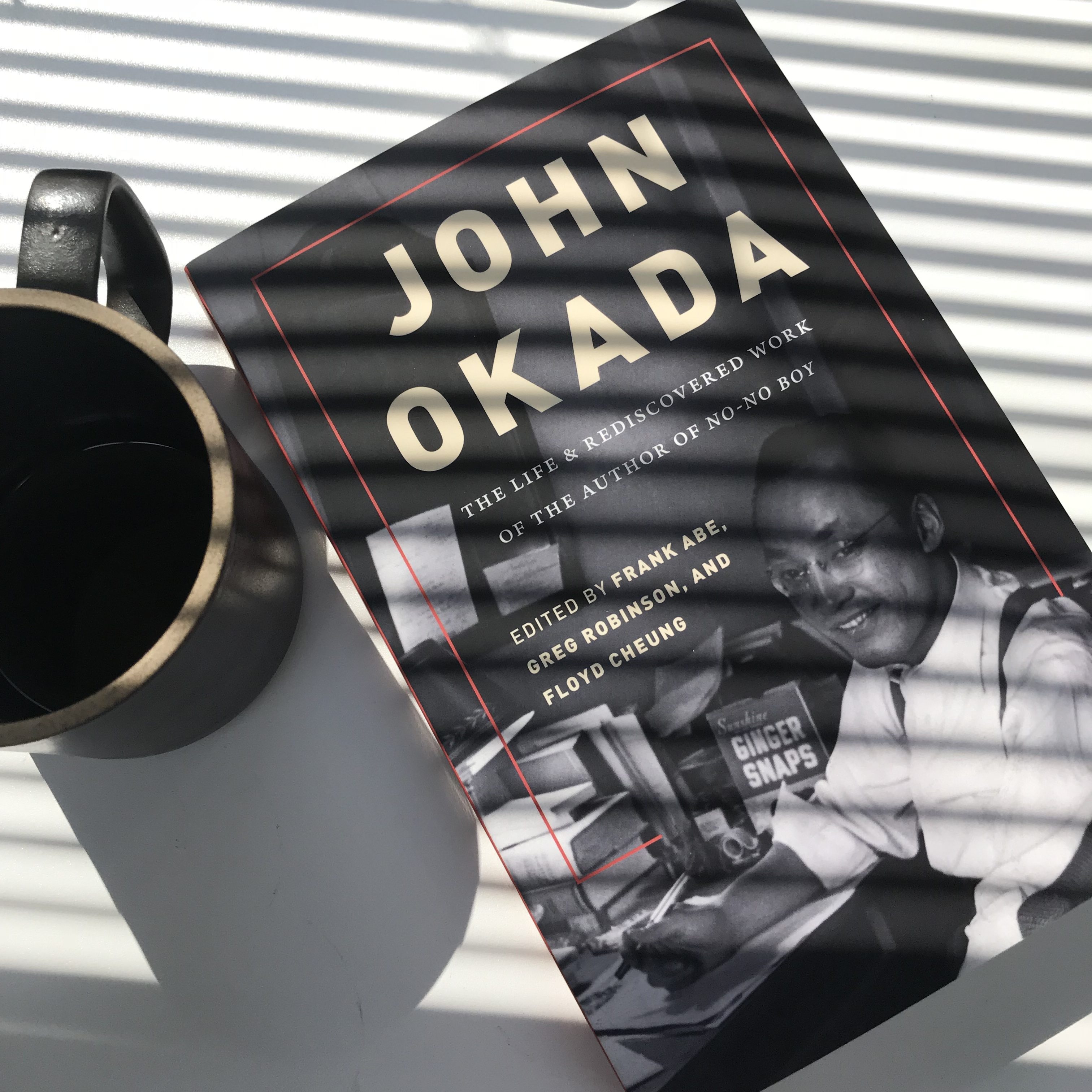

Edited by Frank Abe, Greg Robinson, and Floyd Cheung

John Okada’s No-No Boy is a legendary and foundational work in both Asian American Studies and Japanese American history. First published in 1957, the novel was largely forgotten for over a decade until a group of young Asian American writers rediscovered it in the early 1970s and oversaw its republication. It has since been published by the University of Washington Press in two editions, the latest coming in 2014 and has been a staple of Asian American Studies courses for decades now. If there were an Asian American Literature Hall of Fame, No-No Boy would be a first ballot selection.

Though there has been a small cottage industry of literary scholarship on the book, little has been written about the author, John Okada. John Okada: The Life & Rediscovered Work of the Author of No-No Boy ably fills the gap. The edited volume includes a lengthy biography of Okada by Frank Abe; nine short “Unknown Works” by Okada published both before and after NNB; and seven essays on various aspects of Okada’s life and work.

I should pause here to mention a few things that inform my thoughts on the book. First a couple of disclosures: Two of the editors are friends of both Densho and me, and I am acknowledged by both in the book. I am also a graduate and former employee of the UCLA Asian American Studies Center, and my wife is its current director; center faculty have played a key role in the continuation of the Japanese American Research Project (JARP) that is part of the legend of NNB.

I am also not a particular fan of No No Boy or Okada. I of course acknowledge its significance, its place in history. Coming out when it did, it is a remarkable achievement. As is clear in a brief essay by Shawn Wong, one of its rediscoverers, No No Boy hit young Asian Americans coming of age in the 60s and 70s like a ton of bricks. “It was one of those books that you don’t believe you’re actually reading it when you’re reading it,” he wrote. Its depiction of resistance, rejection of the then prevalent model minority stereotype, and its brutal honesty in depicting the impacts of the wartime incarceration on Japanese Americans set it apart from almost anything being written by Japanese Americans in the 1950s and led to its embrace by Asian American activists a decade or two later—including co-editor Abe and contributors Wong, Stephen H. Sumida, Lawson Fusao Inada, and many others—who were hungry for these things and for its unique voice.

I first read the book as an Asian American Studies graduate student in the mid to late 1980s. The landscape at that time was very different from that of the early 1970s. The Redress Movement was then in full swing, and the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians had famously concluded that the forced removal and incarceration was due to “racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” Perhaps more significantly for me, stories of Japanese American resistance to incarceration had not only become better known, but had become celebrated in Asian American Studies circles by that time. Thus the impact of a work like No No Boy was very different for someone like me than it had been for those coming across it a half generation earlier. It’s probably not unlike a film scholar viewing Birth of a Nation or Psycho years after their initial release: though one can still appreciate their significance, there is no way to recapture the impact of seeing them in the context of their time. Without the visceral impact that No No Boy had for early 1970s readers, all I saw was a slow moving and somewhat melodramatic novel that didn’t even directly address the Japanese American concentration camps.

While John Okada: The Life & Rediscovered Work of the Author, doesn’t necessarily change my views of the book, it certainly expands my knowledge about it. The key piece is Abe’s biography, which takes up more than a third of the book. Given that a key part of No No Boy‘s significance is how it counters the standard Nisei postwar narrative, it is somewhat ironic that Okada’s life story seems to fit neatly into that standard narrative. Born and raised in Seattle, Okada had a typical Nisei upbringing. After graduating from Broadway High in 1941, Okada went with his family to the Puyallup Assembly Center and then the Minidoka, Idaho, concentration camp, while his father was separately interned. Okada spent just three weeks at Minidoka, leaving to go to college in Nebraska, then enlisting and joining the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) where he served in Guam and in occupation Japan. After the war, he embarked on a career as a librarian, technical writer, and in advertising—career choices somewhat influenced by the racism Nisei still faced—while marrying, fathering two children and moving from New York to Seattle to Detroit to Southern California. In between jobs and family, he wrote, publishing No No Boy in 1957. A chain smoker and unhealthy eater (by today’s standards), he died at age 47 in 1971.

The essay is thoroughly researched and gives the reader much insight into Okada and the type of person he was, based on interviews with family members, friends and colleagues. With the exception of the middle sections, on his wartime years, the manuscript is narrowly focused on Okada and his family. This middle section expands the focus to include stories of three of Okada’s draft resister friends whose stories serve as the basis for No No Boy. This material comes across a little awkwardly and might have been better presented as a separate essay on the background of No No Boy. There is also an unhealthy obsession with the Japanese American Citizens League—which plays little or no role in Okada’s life—with gratuitous mentions of them throughout. The ending is also abrupt; it more or less ends with his death and his wife’s disposal of his papers. It would also have been nice to include something on what happened to his wife Dorothy and his children, since we come to know them in the essay, as well as something on his legacy and significance and the later history of No No Boy. Abe also addresses the oft repeated stories by Frank Chin about UCLA’s JARP project purportedly rejecting Okada’s papers including his second novel, leading to Dorothy’s subsequent burning of the papers. While Abe essentially exposes them as fabrications, he stops short of calling them that.

The second section of the book publishes Okada’s other published works which are unlikely to be known to many readers. They include a brief essay and poem he authored as an eighteen-year-old immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor, a short play based on his experiences in the MIS in occupation Japan, five experimental short stories that were published in the Seattle based Japanese American newspaper the Northwest Times in 1947, and two satirical essays based on his days as a technical writer and published in trade journals in the early 1960s. While no doubt interesting for fans of Okada/No No Boy, they didn’t do much for me. However, Floyd Cheung’s essay analyzing the stories as they pertain to No No Boy is convincing and makes a good case for their inclusion.

The other essays besides Cheung’s examine other aspects of No No Boy‘s impact. Greg Robinson’s piece is a typically encyclopedic look at the literary environment out of which No No Boy emerged, convincingly arguing that there was essentially none at the time he wrote the published the book, the active prewar Nisei literary scene having vanished after the war. Literary scholar Sumida’s piece is an insightful close reading of the book, while Jeffrey T. Yamashita’s piece succinctly outlines the voluminous scholarship on No No Boy.

Perhaps the two most significant pieces for me are unfortunately the shortest. Martha Nakagawa’s implicit critique of the book is similar to my own, and she notes how the book “regrettably reinforced several persistent myths about Japanese American resistance to incarceration.” This includes the conflation of “no-no boys” with draft resisters and how Okada’s book about the latter with the title of the former seems to confuse the issue. (In his essay, Sumida somewhat unconvincingly argues that one can be both a “no-no boy” and a draft resister even though the examples he cites answered “no” to only one of the loyalty questions.) Whatever its virtues, Okada’s book has certainly contributed to the general conflation of the two very different types of resistance. Her second critique is the portrayal of the draft resister protagonist of No No Boy as confused, regretful, and full of self-hatred, in contrast to most of the actual draft resisters—including the ones Okada based the book on—who took a principled stand they did not regret.

Shawn Wong’s similarly brief essay describes his and his colleagues’ rediscovery of No No Boy in the late 1960s/early 1970s and its subsequent history from that point forward. As with Nakagawa’s piece, one wishes for more on this topic.

Though not included as part of the book, also worth noting is Robinson’s essay on early reviews of No No Boy that dispels other myths about the initial reaction to it. It is published online on the Discover Nikkei website.

In the end, John Okada is a well edited and worthwhile volume that Okada/No No Boy fans will greatly enjoy and that makes an important contribution to Asian American Studies and Japanese American historical studies.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director