August 6, 2019

Located in Southern Idaho, Minidoka concentration camp opened on August 10, 1942 and held some 13,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. The incarcerees — most of whom hailed from Washington and Oregon — were accustomed to relatively mild climates and struggled to adapt to Minidoka’s extreme temperatures and relentless dust storms. They also endured lesser-known travails. Read on for untold stories of life at Minidoka.

1. “A Source of Unpleasantness and Inconvenience”

Due to a parts shortage, the sewage system was late in being completed, which meant that the flush toilets could not be used initially. Thus, for the first few months at Minidoka, inmates had to use outdoor pit latrines.

“Since we evacuated our bowels into a deep hole, it is very unsanitary,” wrote Issei artist Takuichi Fujii in his diary, which appears in Barbara Johns’ 2017 book The Hope of Another Spring: Takuichi Fujii, Artist and Wartime Witness. “Since it was midsummer, lots of flies had accumulated there. One time there was an epidemic.”

In a December 1942 report, Reports Officer John Bigelow wrote that the “patience of the center residents has been strained to near the breaking point over completion of the sewerage which has been delayed from month to month by the inability of the contractor to obtain certain scarce pieces of equipment.” The outside latrines, he wrote, “have been a source of unpleasantness and inconveniences, especially since the arrival of winter weather—mud, rain, snow, and cold.” The sewer system was finally put into operation at the end of January 1943.

2. Not a Square

Unlike other War Relocation Authority camps, which were either square or rectangular in shape, Minidoka was shaped like a spread-out letter “M,” the blocks laid out along a meandering irrigation canal and stretching nearly three miles from end to end. Though not technically divided into two or three separate camps like Poston and Gila River, there was a natural division between the sixteen residential blocks (1–19) to the north and the twenty (21–44) to the south. (Note that residential blocks were not numbered consecutively.)

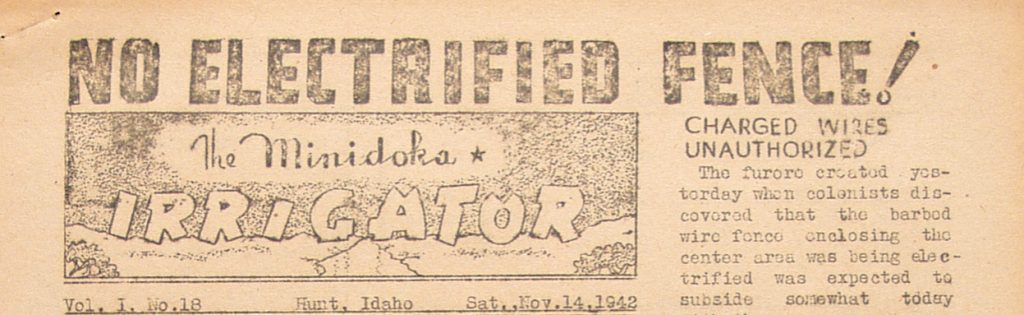

3. The Infamous Fence

While the first months at Minidoka were chaotic—due in large part to much of the camp being unfinished—they were generally peaceful, with no major incidents or unrest. Despite this, construction commenced on a five-foot high barbed wire fence on November 6, 1942, three months after the arrival of the first inmates. The fence blocked off access to garbage dumps and recreational areas in places. Outraged inmates began to sabotage the fence en masse, cutting wires and uprooting posts. Angered at such actions, the contractor electrified the fence on November 12 without the authorization of the army or camp administrators. Though the electrification was turned off after a few hours, outrage continued to build. The fence was completed on December 5. Eight watchtowers were also built.

Reports officer John Bigelow observed in January 1943 that “reaction to the barbed wire fence… isn’t abating,” and that “it continues to be one of the major sources of irritation to the residents.” In April, Community Analyst John de Young noted that “residents are unanimous in possessing deep and bitter resentment against the fence” and that it “became a symbol of their confinement for the residents.” Finally in April, much of the fence was taken down in order to allow access to the farming area and was never replaced. Due to the supply shortages, the guard towers were not completed and were never actually used. Inmates salvaged fence posts to use for garden fences and for other purposes.

4. Gonorrhea Outbreak

In December 1942, an outbreak of gonorrhea took hold, infecting fifteen pregnant women and new mothers. Since none of the husbands were infected, officials concluded that the spread was either through “improper procedure of nurses’ aides” in the obstetrics ward or “the outside latrines which cannot be kept sanitary.” In all, fifty-one women and one man were infected. The outbreak subsided by the end of January 1943.

5. Farm Labor

Due largely to its location near sugar beet and other farming operations in Idaho and other nearby states, Minidoka had perhaps the largest number of inmates leave the camp to do agricultural work on the outside. Some 2,300 left in the fall of 1942 and 2,500 in 1943, representing a substantial portion of the adult population. Many inmates eagerly took the opportunity to do this work, which promised prevailing wages and the opportunity to leave the camp, though their actual experiences were mixed.

Their work in “saving” sugar beet crops garnered positive publicity for Japanese Americans on the outside, but also created serious labor shortages in the camp. To help alleviate this, Hunt High School incorporated weeks long “harvest vacations” in both 1943 and 1944 that allowed high school students to do agricultural work either inside or outside the camp. The mass outflow of laborers also affected recreational activities such as dances, which were canceled in the fall months due to the large number of young men and boys who had left for outside agricultural work.

6. Alaskan Incarcerees

Though Minidoka had one of the most geographically homogeneous populations, a group of about 135 from Alaska stood out from the rest. Camp officials worried about this group, who “had never associated before with Japanese people, cannot speak Japanese, and as a result, they form an isolated group in the center.” The Alaska group was itself quite varied, with about one-third being of mixed-race ancestry, some coming from Alaska Native villages in the north and who hunted whale and seal for a living, and others being business people of some means from the south.

The mixed-race group were mostly those of part Native Alaskan ancestry, though there were also some of part Russian ancestry. Many of this group were children, some of whom were there without parents, whether because their parents were interned elsewhere or were still in Alaska. Others were Japanese American men who had had to leave Native Alaskan wives and children back home. Because the Alaska group were forcibly removed with almost no notice—and because many were land and business owners—they suffered particularly heavy losses. A group that met at the Minidoka Project Attorney’s office in April of 1943 had nearly $1 million in property holdings. A WRA official was dispatched to Alaska to make inquiries on their behalf.

The Empty Chair Project has resulted in a documentary film, book, and memorial commemorating Japanese Americans from Juneau who were forcibly removed and incarcerated at Puyallup and Minidoka. The title comes from the 1942 graduation ceremony of Juneau High School, where students left an empty chair in honor of their classmate and valedictorian John Tanaka, who could not be at the graduation due to his family’s forced removal.

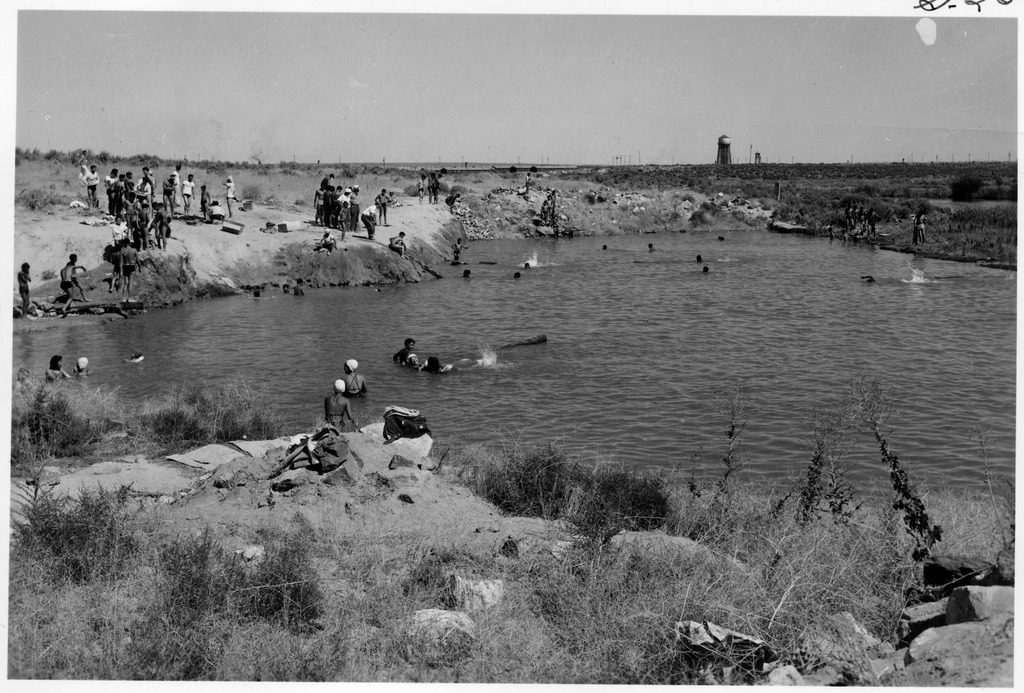

7. Tragedy in the Canal

Many inmates swam in the North Side Canal, which flowed along the southern boundary of the camp, with the tacit approval of the administration. Some also fished in the canal. But in the summer of 1943, tragedy struck twice. Noboru Tada, 11, drowned on June 22, 1943 when he slipped off a rock south of Block 26; Yoshio Tom Tamura, 21, drowned on August 28, 1943, his body recovered by fishermen 2½ miles away. In the aftermath of these deaths, inmates banded together to build a swimming pool that opened later that fall. A second pool was dug near Block 30 in 1944.

8. Greasewood Craze

At many of the WRA concentration camps, a particular type of artistic activity influenced by the surrounding topography took hold. At Minidoka, this activity was the gathering of greasewood by inmates, since objects carved with it could be polished to a high gloss due to its high oil content. Inmates would go miles out into the brush to look for “the most gnarled up ones and the most unusually shaped ones and then use your great imagination to figure out what you can make with,” as George Nakata recalls his father telling another inmate. Canes seemed to be most common item made from greasewood, though inmates made a wide variety of both purely ornamental and utilitarian objects.

The craze led to at least one tragic outcome, when in December 1942, Issei grocery clerk Takaji Edward Abe got lost while searching for greasewood and died of exposure. Some 1,200 volunteers searched for him before his body was found four miles away from the camp.

9. Tule Lake Arrivals

Minidoka was one of the camps that saw a significant influx of inmates from Tule Lake after that camp became the “segregation center” for those deemed “disloyal.” About 1,500 “loyal” inmates from Tule Lake transferred to Minidoka in the fall of 1943. This group impacted Minidoka in a number of ways. Because Minidoka had a relatively small number of “no-nos” go to Minidoka (335, the second fewest from any of the camps), the net influx of over 1,000 led to a housing crisis. As a temporary measure, some families had to be housed in recreation halls that provided even less privacy than regular barracks, while other families were forced to double up. The crisis didn’t start to ease until the spring of 1944, when seasonal workers began to leave the camp.

The Tule Lake group also changed the political dynamics of the camp. Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study fieldworker James Sakoda came to Minidoka with the Tule Lake group and noted both cultural and political divides. The Tule Lake group was a more rural population and Sakoda observed that they commented on how well many of the Minidoka inmates dressed and that they spoke a more polite form of Japanese than the Tule Lake people. Because they also came from a much more contentious environment at Tule Lake, the new arrivals were also much more suspicious of the Minidoka administration and of the Minidoka inmates who cooperated with it. Sakoda observed that Minidoka went from the most “loyal” camp—Minidoka had the second highest percentage of “yes” answers to Question 28 and over 300 volunteers for the army, 25% of the total from WRA camps despite having only 7% of the population—to one that came to resemble Tule Lake, after the arrival of the Tule Lake group. Unrest did indeed spike in 1944.

10. Labor Unrest

Due to the cutback in inmate workers in 1943, the ongoing shortage of workers, and other factors, much labor unrest took place in the last two years of the camp. In January of 1944, for instance, a strike by some 160 boilermen and janitors left inmates without hot water for a week in the dead of winter. They were protesting a dramatic decrease in the workforce that forced remaining workers into longer hours. Similar work stoppages took place with mail carriers, warehouse workers, garbagemen and others. Cooks staged slowdown strikes in 1945 in protest of administration plans to close mess halls as block populations dropped. Workers building the high school gym also engaged in slowdowns that resulted in the gym never being completed.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

The information presented here has been excerpted from Densho’s new and improved Sites of Shame project, coming to a device near you in 2020. Full citations will be included there, but feel free to post questions in the comments or email us at info@densho.org in the meantime!

[Header photo: Dorothy and Jack Yamaguchi, pictured in the middle and to the far right, with their children and the children’s grandmother, were from Seattle, Washington. The Yamaguchis returned to Seattle after World War II and worked to help preserve Japanese American history. They developed a slide show and accompanying book called “This is Minidoka,” which they used to educate schoolchildren about the camp experience. Courtesy of the Wing Luke Asian Museum, the Hatate Collection.]