September 29, 2017

On December 7, 1941, Sumi Okamoto, then 21, was busy getting ready for her wedding. Oblivious to the reports of bombs falling on faraway Pearl Harbor, Sumi put on her white dress and headed to the Grant Street Methodist Church in Spokane, Washington. Her family and friends, hoping not to spoil her wedding day, tried to keep the bad news from her — that is, until FBI agents crashed the reception to arrest several of her Issei guests.

This is not an uncommon story. Lilly Irinaga’s father was picked up in another mass arrest at a community event in Portland. Ryohei Miyaki was removed from his Terminal Island home by an informal posse deputized to act on behalf of the FBI. What Akira Otani remembered was the guns they pointed at his mother as they dragged his dad to a waiting car. My own great-grandfather, Takuichi Kubota — George to the white folks who couldn’t pronounce his birth name — was taken quietly and efficiently, without a word on where he was going or when (if) he would be back.

In the weeks following Pearl Harbor, these raids became such a regular occurrence that many men began to keep a suitcase with a toothbrush and change of clothes by the door, awaiting their turn to disappear.

But this roundup of Issei community leaders was much more than simple hysteria. For years, the government had prepared for the detention of prominent Issei, made contingency plans for the systematic removal of Nikkei communities, and even toyed with the idea of holding Japanese Americans as wartime hostages. This was, as professor Tetsuden Kashima describes in Judgment Without Trial, “a rational process, not one conceived in haste or necessitated by administrative panic.”1

The ‘Japanese Problem’

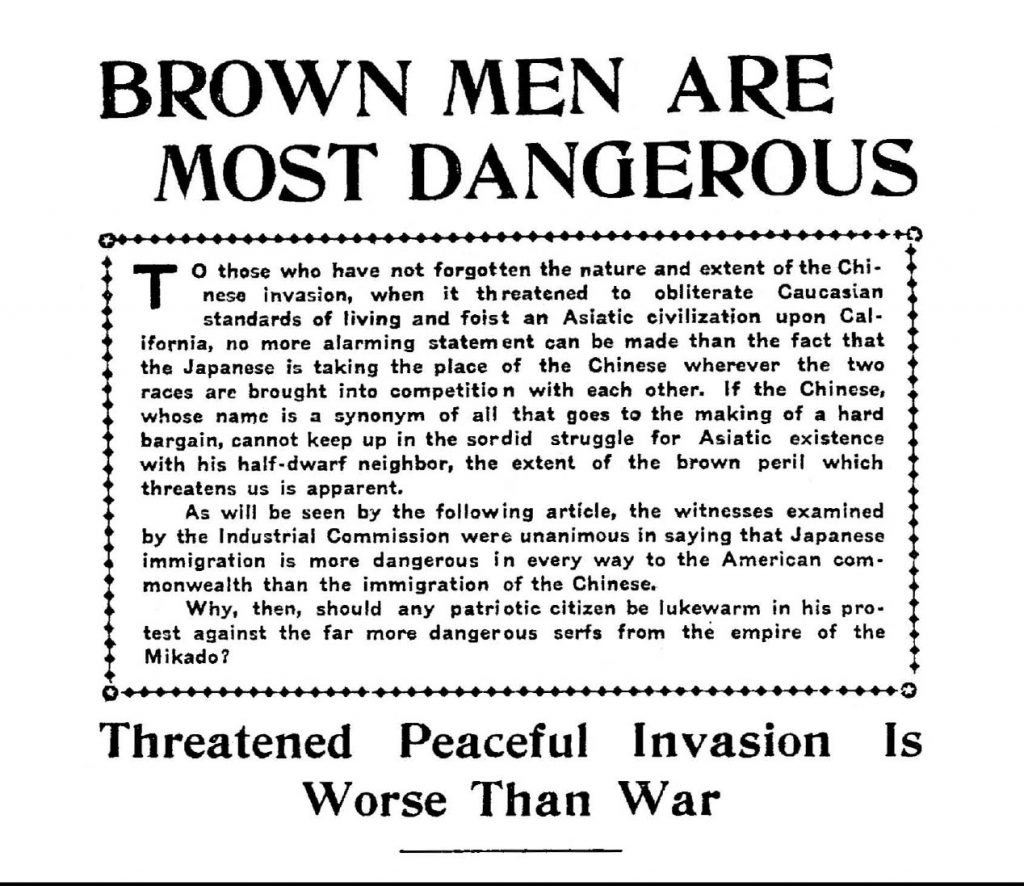

Japanese Americans had been declared an enemy of the United States long before the war. Issei immigrants arriving on the West Coast and Hawai`i in the early 20th century were met with vehement, sometimes violent opposition. Anti-Japanese crusaders seeking to drive out “the yellow menace” cast these immigrants as an invasive species infiltrating the country in preparation for “colonization” by Japan. This “Japanese problem” was largely framed as a battle for self-preservation: The racial and moral purity of (white) America was under attack by a barbaric horde of “tiny brown men” and their overly fertile wives.

As communities of color became increasingly organized in their attempts to address the systemic racism leveled against them, government surveillance became a tool to undermine and suppress activism. The FBI monitored plantation labor organizers in Hawai`i from 1917, and showed concern over “Japanese subversives” involved with the Universal Negro Improvement Association and the Nation of Islam as early as 1920. J. Edgar Hoover saw Japanese support for Black nationalist groups as evidence of a militant coalition of Black and Asian radicals uniting “the colored races” against “the white man’s rule.” This opinion was reflected in the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), which expressed fear of “the Japanese hand playing the powerful yet silent note” behind “the negro movement” and other “agitory elements.”2

American counterintelligence efforts began to prioritize domestic surveillance of purportedly subversive activities, initially targeting anarchists, communists, and labor unions. But as war with Japan loomed closer, US officials grew increasingly paranoid of a fifth column composed of the Issei and their citizen children — a delusion no doubt influenced by earlier propaganda warning of a Japanese invasion. The ONI, FBI, War Department, and other federal agencies soon turned their attention to Japanese Americans.

Ostensibly this surveillance was aimed at Japan, but in keeping with longstanding perceptions of Asian Americans as duplicitous and inassimilable foreigners, Nikkei residents and citizens of the United States were also suspect from the beginning. US-Japan relations soured in the early 1930s, as the American government became increasingly concerned that Japan’s military occupation of China and Korea would threaten Western colonial stakes throughout Asia and the Pacific. Japanese Americans were implicated by association, and by 1932 the entire community was under active surveillance.3

‘An apocalyptic picture of disloyalty and danger’

Hawai`i, with its large Nikkei population and relative proximity to Japan, was of particular concern. John DeWitt, one of the main architects of WWII incarceration, had in the 1920s overseen the formation of a “Joint Defense Plan” in Oahu that included contingencies for imposing martial law, suspending habeas corpus, and the registration and selective internment of Japanese “enemy aliens.” Japanese Americans living in the territory were monitored by multiple investigative agencies, and reports were compiled detailing “an apocalyptic picture of Japanese American disloyalty and danger.”4

How much of this information reached the White House is unclear, but one area that did elicit special attention from President Roosevelt was the interaction between Japanese Americans and the crew members of Japanese commercial ships passing through Oahu. Officers and crewmen delivered mail from Japan, patronized Japanese-owned hotels and restaurants, and visited local temples and schools — which intelligence authorities interpreted as a strategy “to advance Japanese nationalism and to cement bonds of loyalty.” In August 1936, Roosevelt charged a joint Army-Navy task force with “secretly but definitely” identifying Japanese Americans with “any connection” to Japanese sailors, suggesting they be “placed on a special list of those who would be the first to be placed in a concentration camp in the event of trouble.”5

Authorities on the mainland shared this fear of Japanese American spies at sea. Texas Congressman Martin Dies — a super chill dude who would later go on to investigate the wardens of WWII incarceration for supposedly “coddling” inmates — claimed fishermen in California were “under the direct domination of Japan and cooperating fully with their mother country in fifth column spy and traitor activities.”6 In 1937, the ONI ordered its West Coast district offices to conduct a survey of all Japanese American fishing boats. Thanks to cooperation from the Coast Guard, investigators had compiled an extensive file on every Japanese or Japanese American fishing vessel in southern California by early 1941.7

But Nikkei fishermen were far from the only subjects of governmental concern. The ONI had since the early 1930s compiled a list of organizations and individuals viewed as an actual or potential threat to national security. Eighty-eight organizations were designated a high-risk “A” level threat. Another 176 were deemed a “B” level or potential threat, and many “C” level businesses were monitored as “Semi-Official and Subversive Japanese firms.”8

Membership in one of these organizations was one of many ways to land on a federal watchlist. Investigators were “generous with the title of suspect,” as one State Department official put it, flagging individuals for “merely making a speech in favor of Japan,” heading a dojo, or subscribing to “nationalist” magazines, to name but a few offenses.9 Men who held prominent positions within the community — Japanese language school instructors, Shinto priests, leaders of kenjinkai or other cultural associations — also attracted the suspicion of federal agents. In Los Angeles County alone, almost 5,000 Japanese Americans had been blacklisted as “potentially subversive” by 1940.10

If agents were unscrupulous about the quality of their information, they were equally so when it came to their methods of collecting it. The ONI engaged in some seriously shady tactics, frequently resorting to illegal wiretaps, opening mail, accessing private bank accounts, and breaking into the offices and residences of suspected spies.11 In one case, authorities even “borrowed” a safecracker from a local prison to assist in a burglary.

Informants and ‘Unlikely Saboteurs’

Fears of Japanese spies were not necessarily without merit. Authorities did uncover espionage attempts linked to the Imperial Navy, particularly in southern California where the country’s defense industries were concentrated. The 1930s also saw a rise in Japanese nationalism among some Japanese Americans — largely in response to the blatant anti-Japanese discrimination that had been increasingly coded into US law during the previous two decades.12 But the idea of a widespread conspiracy rooted in the larger Japanese American community was more fiction than fact. In reality, Japanese intelligence agents were wary of recruiting Nisei and even Issei as informants, seeing them “not as potential allies but as cultural traitors not to be trusted.”13 Suspicion toward Japanese Americans was one thing the US and Japan had in common.

Realizing that this made the Nisei “unlikely saboteurs,” J. Edgar Hoover and other officials instructed their agents to cultivate informants within the Japanese American community. Togo Tanaka, unofficial historian of the Japanese American Citizens League, claimed that federal investigators made “personal contact” with national officers of the JACL between 1940 and 1941, while chapter leaders were “increasingly approached” by both federal and local law enforcement.14

The JACL had long advocated for assimilation and a hearty showing of American patriotism as the best way to combat discrimination. As it became increasingly clear that war with Japan was merely a matter of time, a segment of JACL leadership “responded with a patriotic zeal” and took it upon themselves “to judge and evaluate the loyalty of members of the Japanese community.”15 Viewing it as their contribution to the war effort, they passed on the names of Issei and Kibei suspected of subversion, and aided federal authorities with intelligence gathering.

Naval Intelligence Officer Kenneth Ringle was one of these authorities. Hailing from the ONI’s 11th District in southern California, Ringle was charged with assessing the loyalty of Japanese Americans on the West Coast in July 1940. Over the course of his two-year investigation, he built a network of informants within the Japanese American community, particularly among members of the JACL — although the bulk of the names Ringle contributed to the ONI’s suspect list came from a late-night break in to the Japanese consulate in Los Angeles.

Curtis Munson, commissioned to investigate the “Japanese situation” for the White House in the fall of 1941, retraced Ringle’s steps and relied on many of the same sources. Both men reached the same conclusion: there was no evidence of widespread disloyalty, and the vast majority of Japanese Americans were unlikely to participate in any “anti-American activities.” They urged against mass exclusion, and extolled the patriotic virtues of the American-born Nisei, whom Munson described, dripping with condescension, as “pathetically eager to show this loyalty.”16

The ‘Alien Enemy Control Program’

Ironically, most of that major surveillance program ended up disproving the government’s suspicions. In well over a decade of investigating Japanese Americans, no fifth column was ever discovered, no double agents, no terror cells or subversive plots. But despite this exonerating evidence, most of the key intelligence figures still harbored doubts about the “enemy alien” Issei. Ringle, Munson, Hoover, and others within the Navy and Department of Justice may have opposed the wholesale incarceration of Japanese American citizens, but they had no qualms about detaining immigrants as a preventative measure.

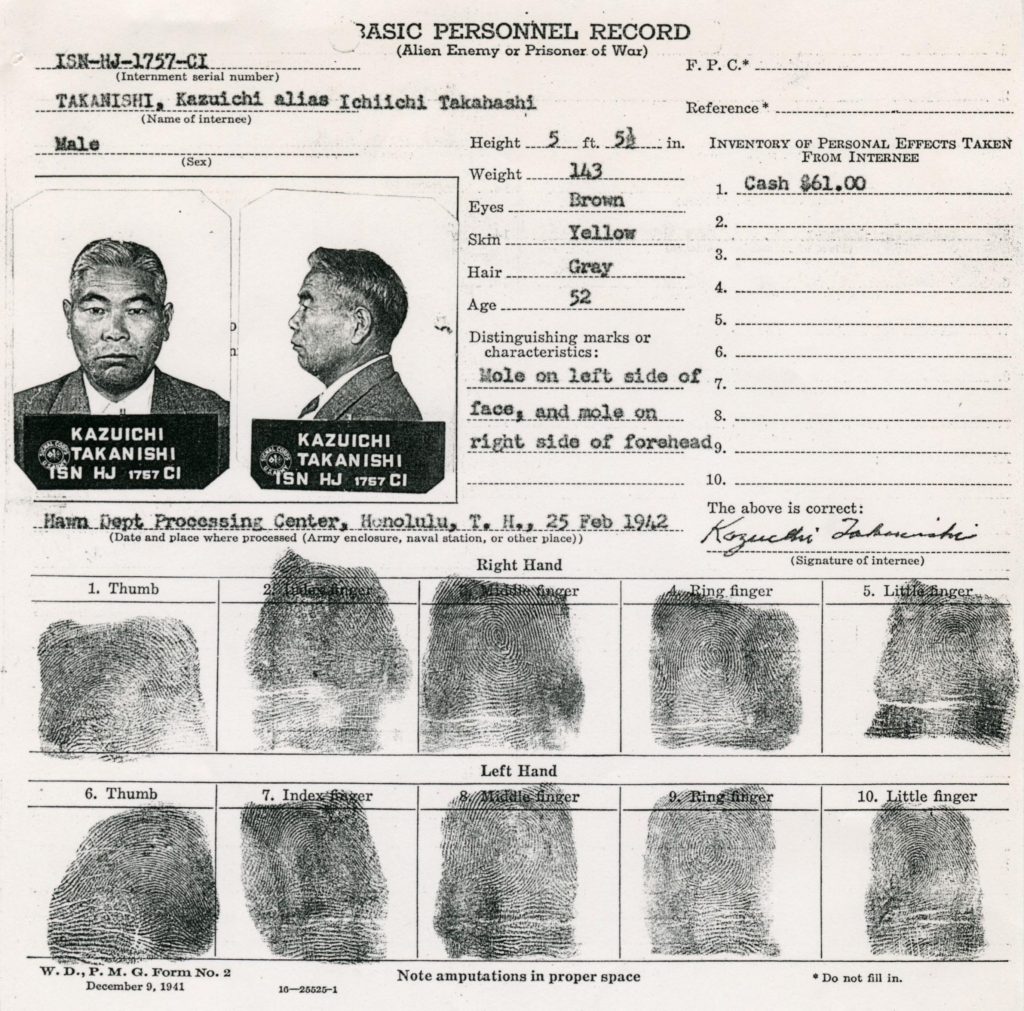

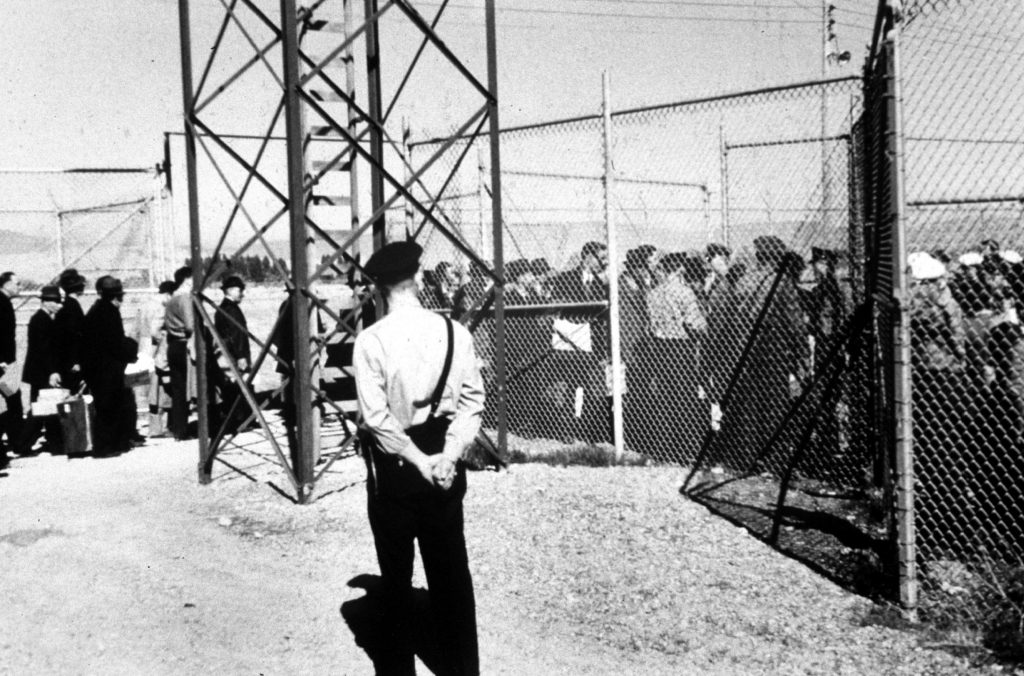

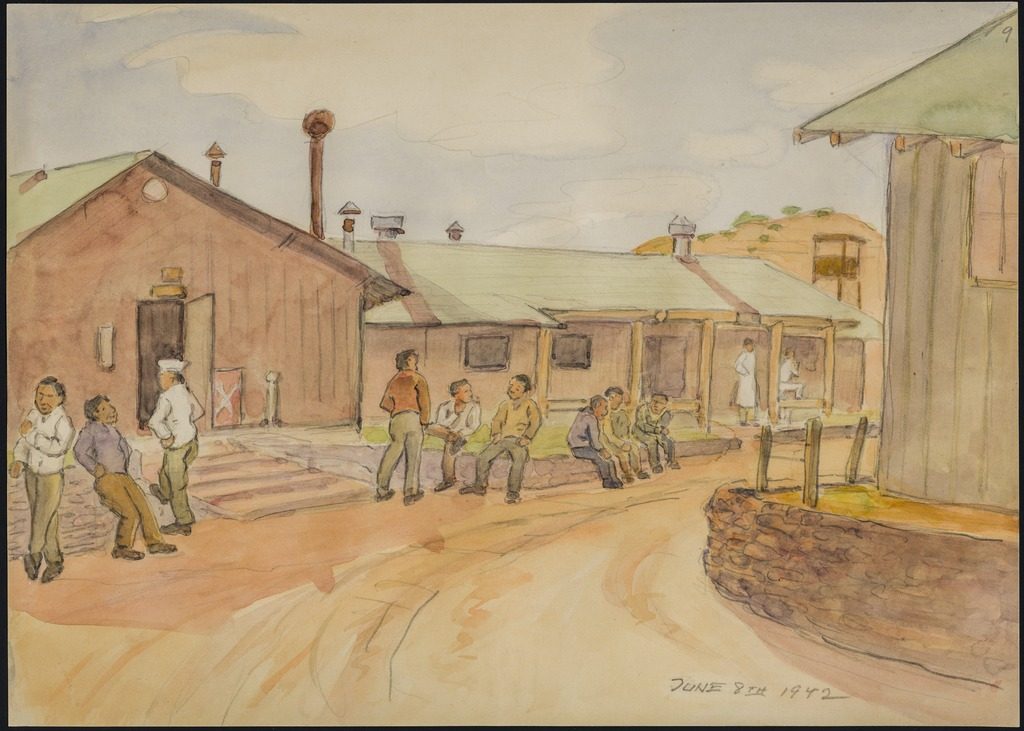

Relying on suspect lists compiled in the years leading up to Pearl Harbor, federal agents and local law enforcement began arresting the mostly Issei men blacklisted as potential terrorists within hours of the attack — before an actual declaration of war, and largely without warrants or formal charges. After languishing in local jails and immigration stations for weeks at a time, these prisoners were, in accordance with a pre-existing agreement between the DOJ and War Department, eventually transferred to POW-style internment camps to await hearings.

Ultimately, nearly 9,000 Japanese Americans were caught up in what was euphemistically dubbed the “Alien Enemy Control Program.” Denied citizenship under racist naturalization laws that singled out Asian immigrants, these prisoners (most of whom had lived and worked in the US for at least fifteen years) had few opportunities for legal recourse.

The Alien Enemy Hearing Boards that decided their fate consisted mainly of “prominent civilians” qualified by their status as well-respected white gentlemen rather than any legal expertise. While some detainees in Hawai`i had access to legal counsel, those on the mainland (whose hearings usually lasted less than 30 minutes) were not allowed to have a lawyer present. Both groups were prohibited from challenging any evidence brought against them — which was mostly limited to hearsay and racialized accusations of disloyalty. Even for those who received a favorable ruling, the victory was short-lived: parolees were simply “released” to one of the ten WRA concentration camps. Those judged too dangerous for release remained in DOJ custody for the duration of the war.17

This initial roundup proved to be a trial run for the full-scale removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. Regardless of its original conception as an alternative to mass incarceration, and in spite of the evidence disproving any supposed threat to national security, attempts to “control” Nikkei communities did not end with the selective internment of foreign nationals. Anti-Japanese zealots, capitalizing on existing fears and prejudices, emboldened by the silence of politer racists and white liberals “disinclined to insist,” soon called for more extreme measures — and we all know how that turned out.

The surveillance state lives on

This was not the government’s first or last attempt at weaponizing intelligence to exert power over a vulnerable and hyper-visible minority. From the FBI’s early interest in labor organizers and Black nationalists to the infamous COINTELPRO; post-9/11 Muslim registries to today’s Countering Violent Extremism program; predictive policing; data collection on social media; federal agents infiltrating mosques and compiling dossiers on Black Lives Matter and Standing Rock activists — casting people of color as a national security threat in order to justify the invasion of their privacy (or worse) is a recurring theme in American history.

The extensive surveillance and criminalization of Japanese Americans in the decades leading up to World War II, and the extra-judicial roundup of some 9,000 Japanese immigrants that resulted from it, fits squarely into this history. It can also teach us a great deal about contemporary threats to the civil liberties of Black, Muslim, South Asian, and other marginalized communities. There are valuable lessons to be learned — if we are willing to listen — about policing loyalty and criminalizing dissent, about sacrificing the safety of “them” for the comfort of “us.”

My great-uncle once told me that what he felt when his father was arrested in 1942, more than anything else, was shame. The handcuffs — shame. His mother’s silence — shame. The looks of pity and curiosity at school the next day — shame.

As we continue to see abuses of power excused by imagined security crises, we must ask ourselves, what are we doing to shift the burden of that shame to where it belongs? How are we disrupting the repetition of this history and building bridges with those most impacted by state violence today?18 “Never Again,” “Never Forget,” “Nidoto Nai Yoni” — these are more than hashtags or feel-good platitudes. This is a promise to those who came before us and those who will inherit what we leave behind. It’s a promise we must keep.

—

By Nina Wallace, Densho Communications Coordinator

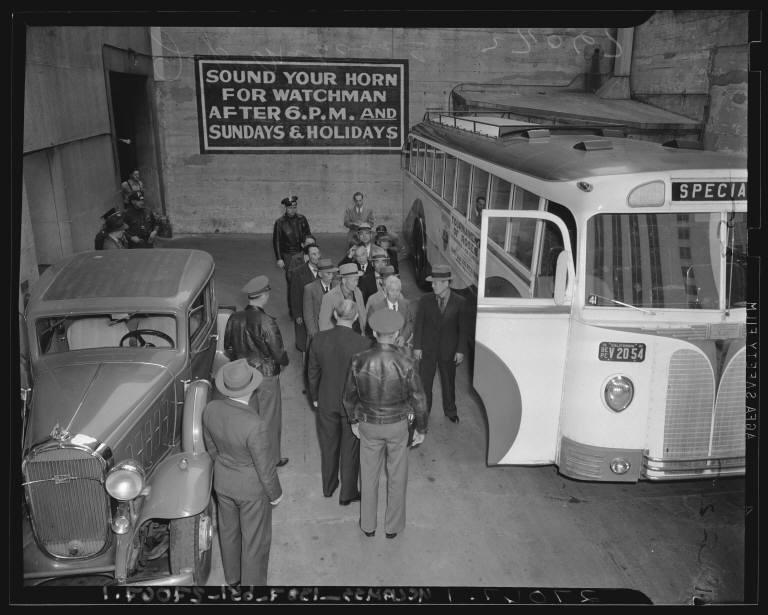

[Header photo: A policeman frisks a Japanese man arrested in a roundup after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. Courtesy of the Associated Press.]

Notes:

- Tetsuden Kashima. Judgment Without Trial: Japanese American Imprisonment during World War II (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003), 14. ↩︎

- Kashima, 15-19. ↩︎

- Pedro A. Loureiro, “Japanese Espionage and American Countermeasures in Pre-Pearl Harbor California.” The Journal of American-East Asian Relations, Vol. III, No. 3 (Fall 1994), 199. ↩︎

- Greg Robinson. By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001) , 54-57. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Loureiro, 197. ↩︎

- Loureiro, 200-01. ↩︎

- Tetsuden Kashima, “Custodial detention / A-B-C list.” Densho Encyclopedia. ↩︎

- Loureiro, 200. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Kashima, 37. ↩︎

- Yuji Ichioka. Before Internment: Essays in Prewar Japanese American History, ed. Gordon H. Chang and Eiichiro Azuma (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006). ↩︎

- Loureiro, 205. ↩︎

- Togo Tanaka, “History of JACL.” Quoted in The Lim Report: A Research Report of Japanese Americans in American Concentration Camps during World War II, Deborah K. Lim (Kearney, NE: Morris Publishing, 2002), 3-5. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Curtis B. Munson, “Japanese on the West Coast” (accessible at http://www.michiweglyn.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/Munson-Report.pdf); Kenneth D. Ringle, “Report on the Japanese Question” (accessible at http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-67-9/) ↩︎

- Kashima, 58-64. ↩︎

- See “Disruptors and Bridge Builders” in We Too Sing America: South Asian, Arab, Muslim, and Sikh Immigrants Shape Our Multiracial Future, Deepa Iyer (New York: The New Press, 2015). ↩︎