April 5, 2016

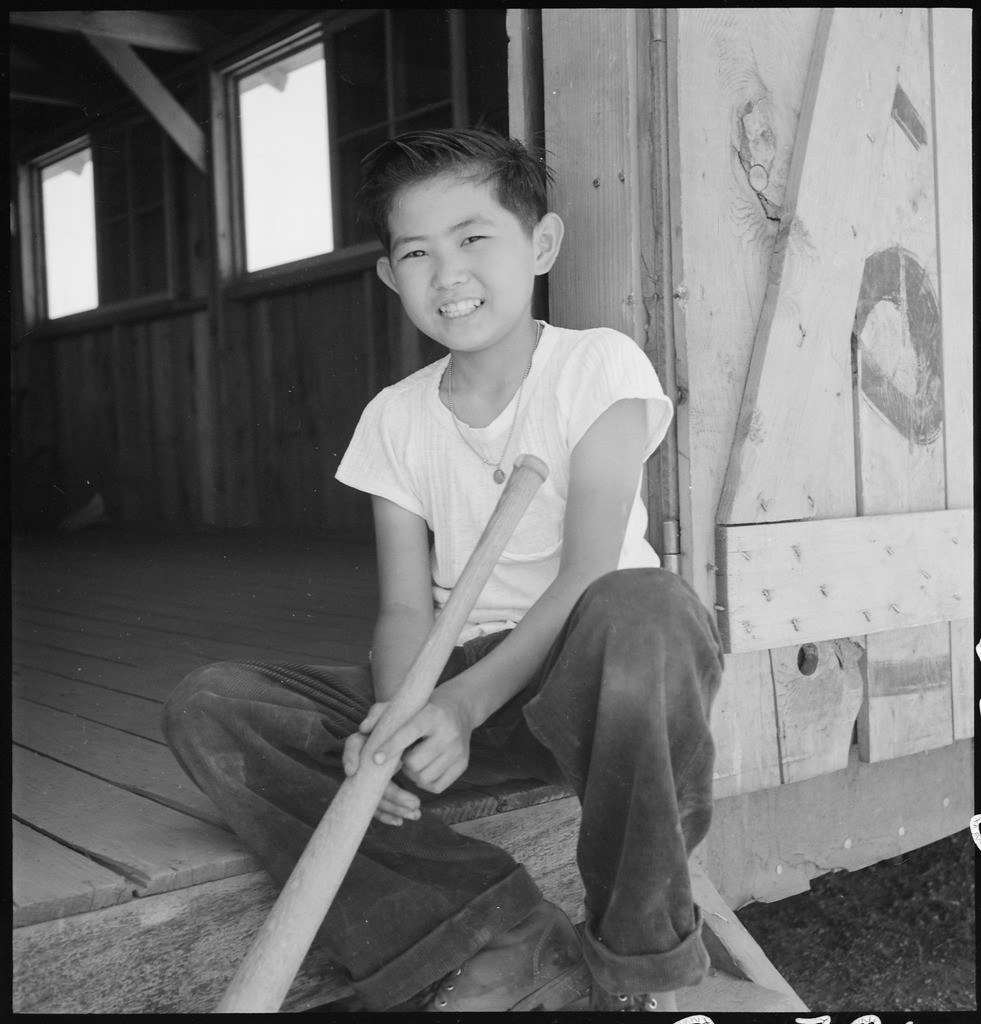

Baseball season is here again! This favorite of American sports was also a popular pastime in Japanese American concentration camps. Here we delve into that history through an excerpt from Terumi Rafferty-Osaki’s encyclopedia entry on sports in World War II concentration camps. Scroll down for a photo essay and additional baseball resources from Densho Content Director Brian Niiya.

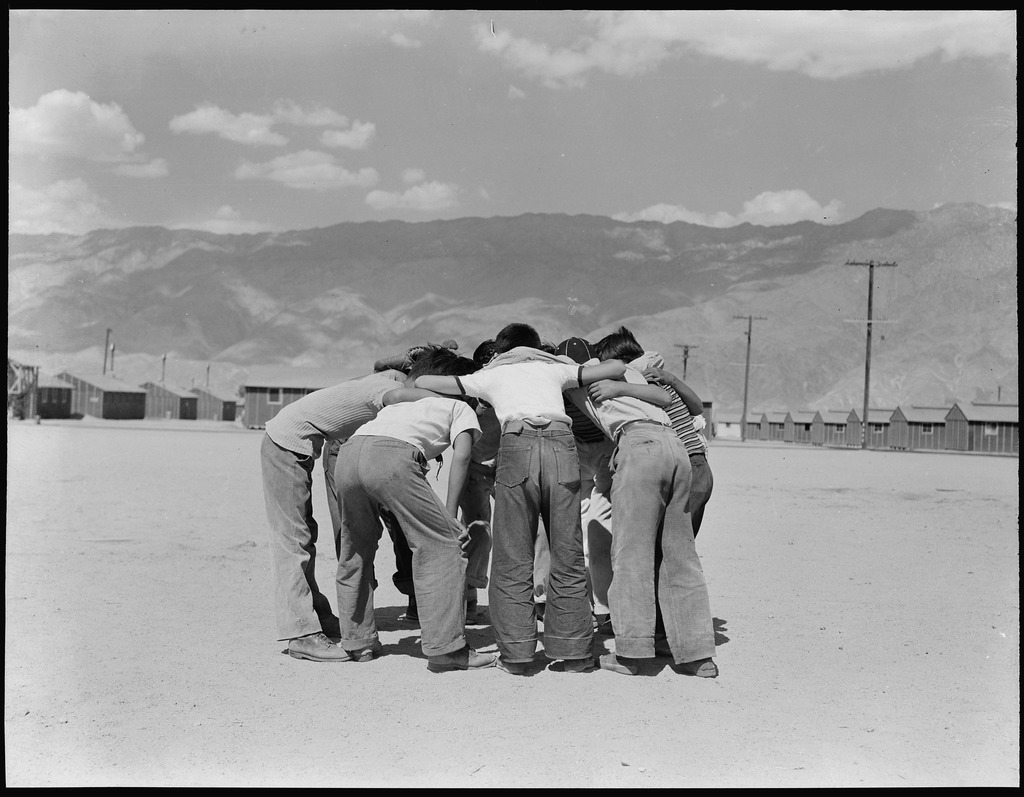

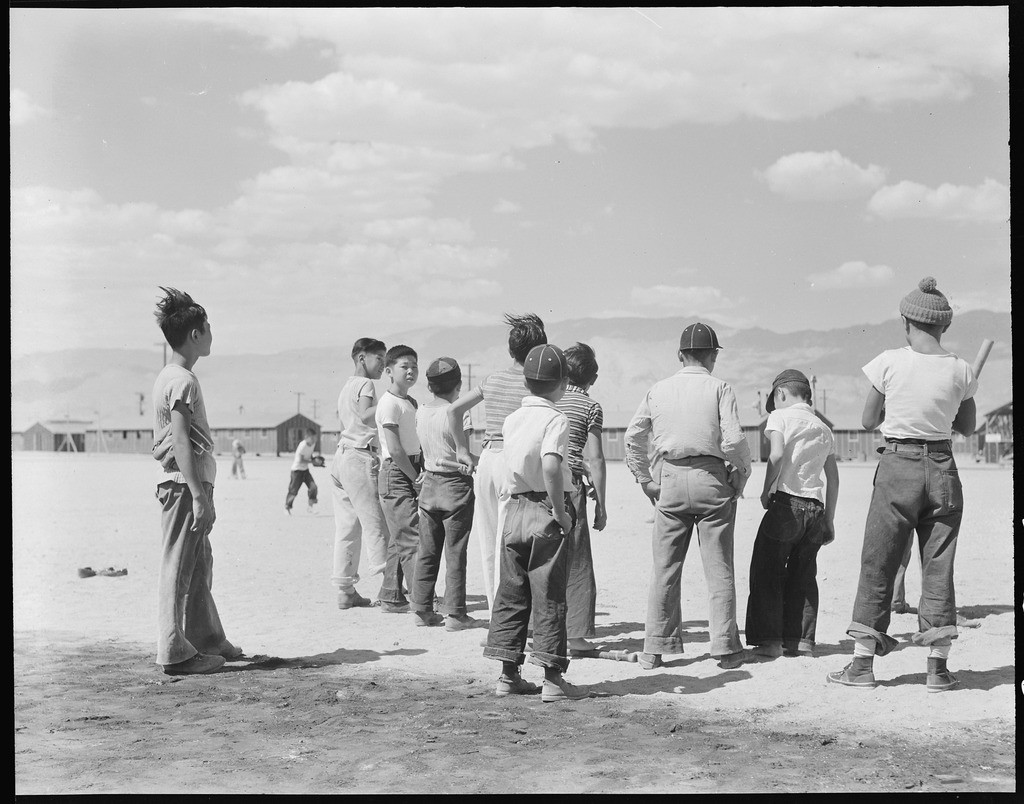

When Nikkei inmates transferred to the ten War Relocation Authority centers, they brought their sports programs along with them. Baseball and softball remained the premier sports. According to Kerry Yo Nakagawa, despite obstacles unique to each camp, inmates designed and built baseball diamonds mainly during 1942, the first year in the camps. Famed “Dean of the Diamond,” Kenichi Zenimura, with volunteers from throughout the Gila River concentration camp struggled to clear away the ubiquitous sagebrush and then faced the challenge of developing methods to reduce dust on the arid fields of Arizona. In an interview with Nakagawa, actor and former Gila River incarceree Pat Morita remembers “watching a little old brown guy watering down the infield with this huge hose. He used to have his kids dragging the infield and throwing out all the rocks…They worked like mules.” Similar backbreaking work went into baseball fields in Manzanar and Rohwer, while at the Jerome center, incarcerees removed tree stumps with dynamite provided by WRA officials.

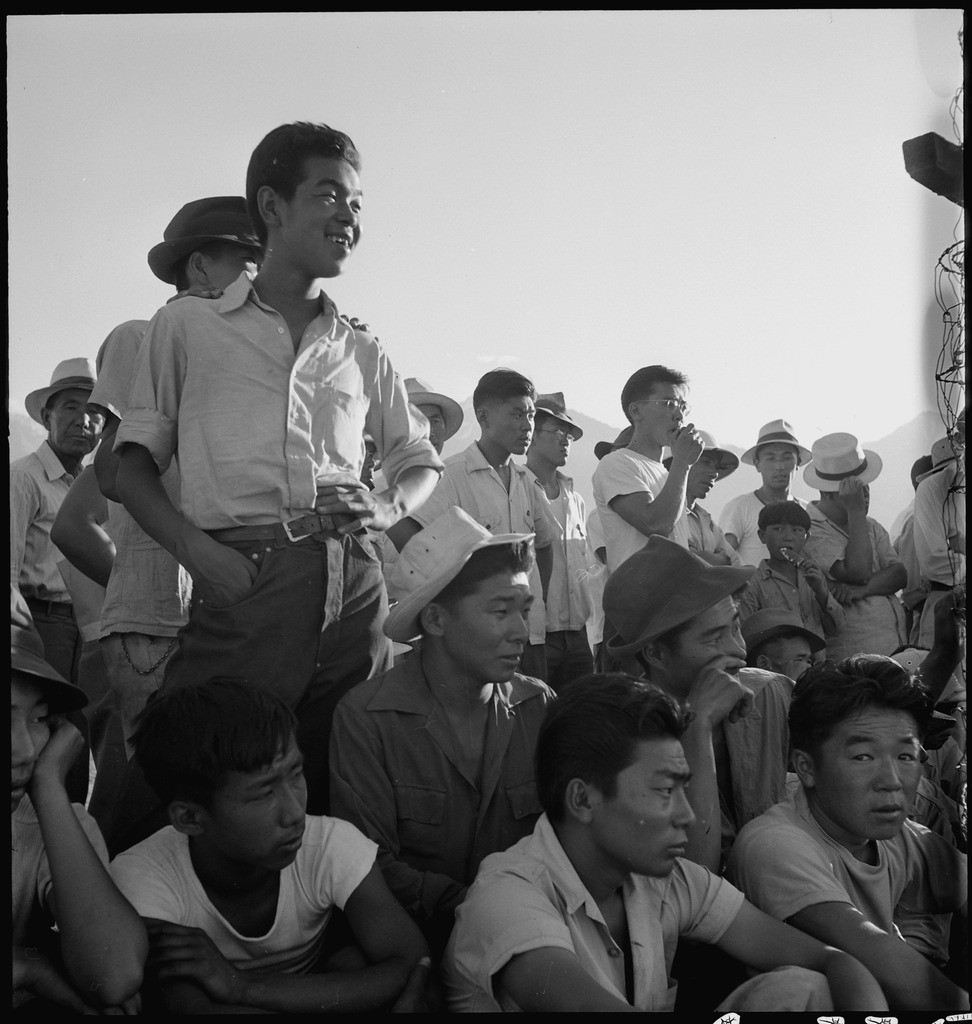

Beginning in 1943, incarceration camps hosted many interracial baseball games behind barbed wire. Idaho incarcerees even traveled outside of the center to the state tournament. As early as June 1943, the camp guards of Rohwer participated in softball games against the Nikkei inmates with the military police team led by Stg. Burke, a former semi-pro player, defeating the Japanese American Royal Dukes by a tally of 7-1. From July 25 to 31, 1943, sixteen Nisei players from Hunt/Minidoka incarceration camp made a 150-mile trip to the Fifth Annual Idaho State Semi-Professional Tournament at Idaho Falls. In the quarterfinal match, the Nikkei prisoner team played the Hunt Military Police Force, guards from the Minidoka camp, winning by a tally of 14-1. In May and July 1943, Jiggs Yamada and Ship Tamai of Tule Lake put together a game against the Klamath Fall Pelicans and another battling a white semi-pro All Star team from the Oregon League. The Tulean All-Stars won both affairs against the “invading” Caucasian teams by a score of 16-0 and 16-8 in front of nearly 5,000 Nikkei fans. No one doubted the talent of Japanese American players.

The 1944 baseball season reflected the loosening of restrictions on Nikkei inmates deemed “loyal” to the U.S. Under the leadership of Zenimura, a series of inter-camp games took place in the summer and fall. The first series took place in June 1944 featuring an All Star team from Poston (Arizona) that traveled 200 miles to Gila River. Ironically, when prisoners donned baseball uniforms, the WRA provided these “enemy aliens” a bus to travel the long distances between centers to the inter-camp games unguarded—almost as though the baseball uniform conveyed greater acceptance as part of American culture.

The six game series between the two camps ended with a series split. Members from the Poston group thanked the Gila River center before they left for their journey back to their camp. Gila River then welcomed the Amache players who trekked 900 miles from Colorado to play a series of baseball games. Gila River reciprocated and made the journey to Amache later in the season. Zenimura worked on a schedule for play and in the end, Gila River swept Amache in all eight games they played at each center. Most members of the All-Star team from Amache camp that participated in this series were bound for service in the United States Army’s segregated all-Nikkei 442nd Regimental Combat Team. In September 1944, another inter-camp series took place between the Heart Mountain All-Star and the Gila River Internees. The Gila River team led by Zenimura made an 1,170-mile pilgrimage to Heart Mountain (Wyoming) to play thirteen games.

Reading recommendations from Densho Content Director Brian Niiya: